|

ACTIVISM

The Big Reason Young People Don’t Debate Gun Control the Way Older Generations Do

A dramatic 25-year reduction in gun violence among youth puts high schoolers in a unique position to influence debate.

Photo Credit: Screen Capture / Democracy Now!

Gun control advocates are celebrating the thousands of teenagers demanding that gun massacres like the latest at Parkland, Florida’s, Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School “Never Again” happen.

But does politics offer a remedy? Gun violence discussion among adults is already retreating once again into an easy consensus: the problem is just about “kids”—deranged young shooters, and protecting “children” terrified of gun-menaced schools. Quick remedies are emerging from the White House and other political leaders: just raise the age for firearms purchases, pack schools with more cops, arm the teachers, install more security hardware, and widen the net of intrusive “mental health” regimes targeting young misfits.

But America’s gun violence epidemic only can be reduced through effective, enforced legislative policies—or simply by fewer people shooting people.

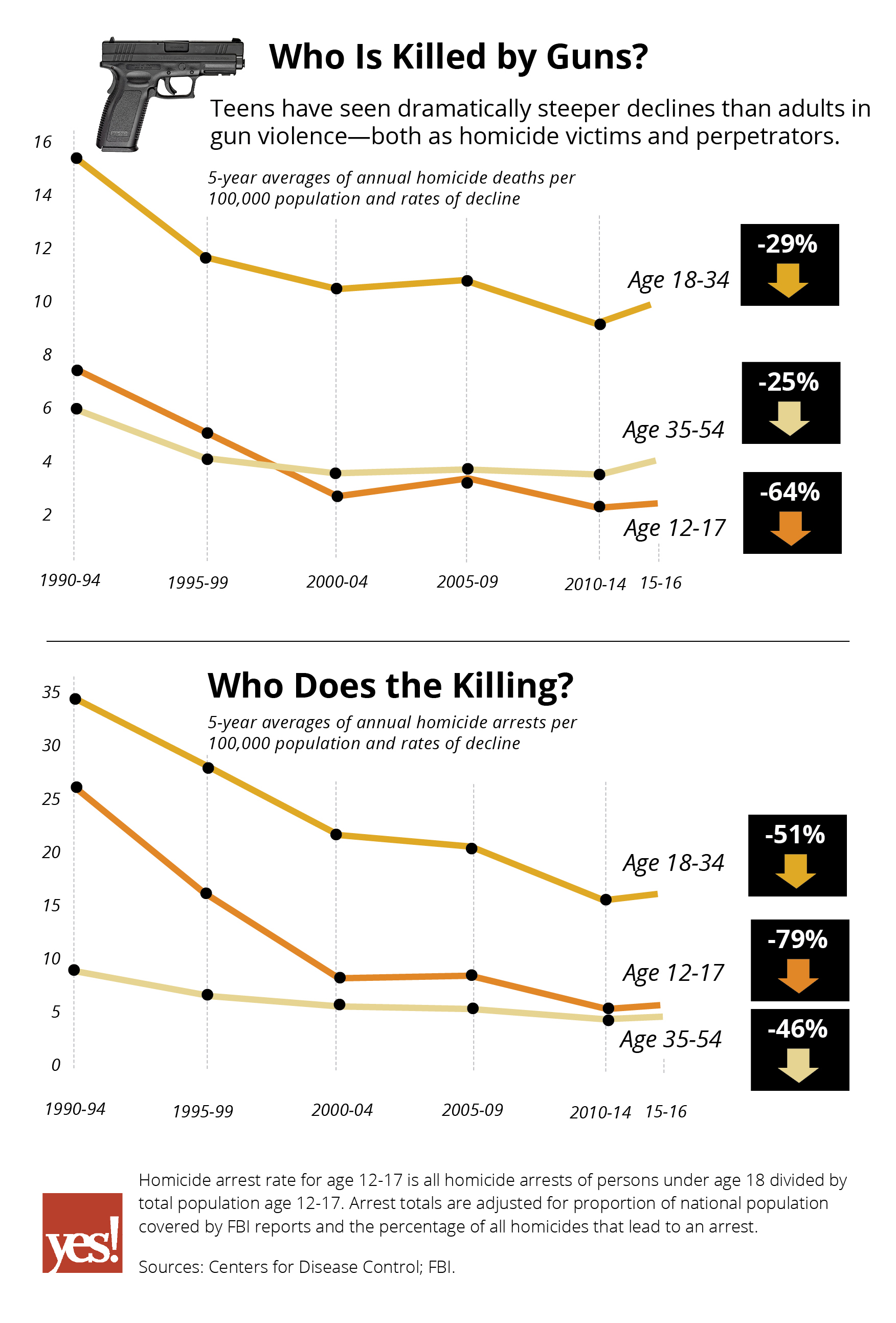

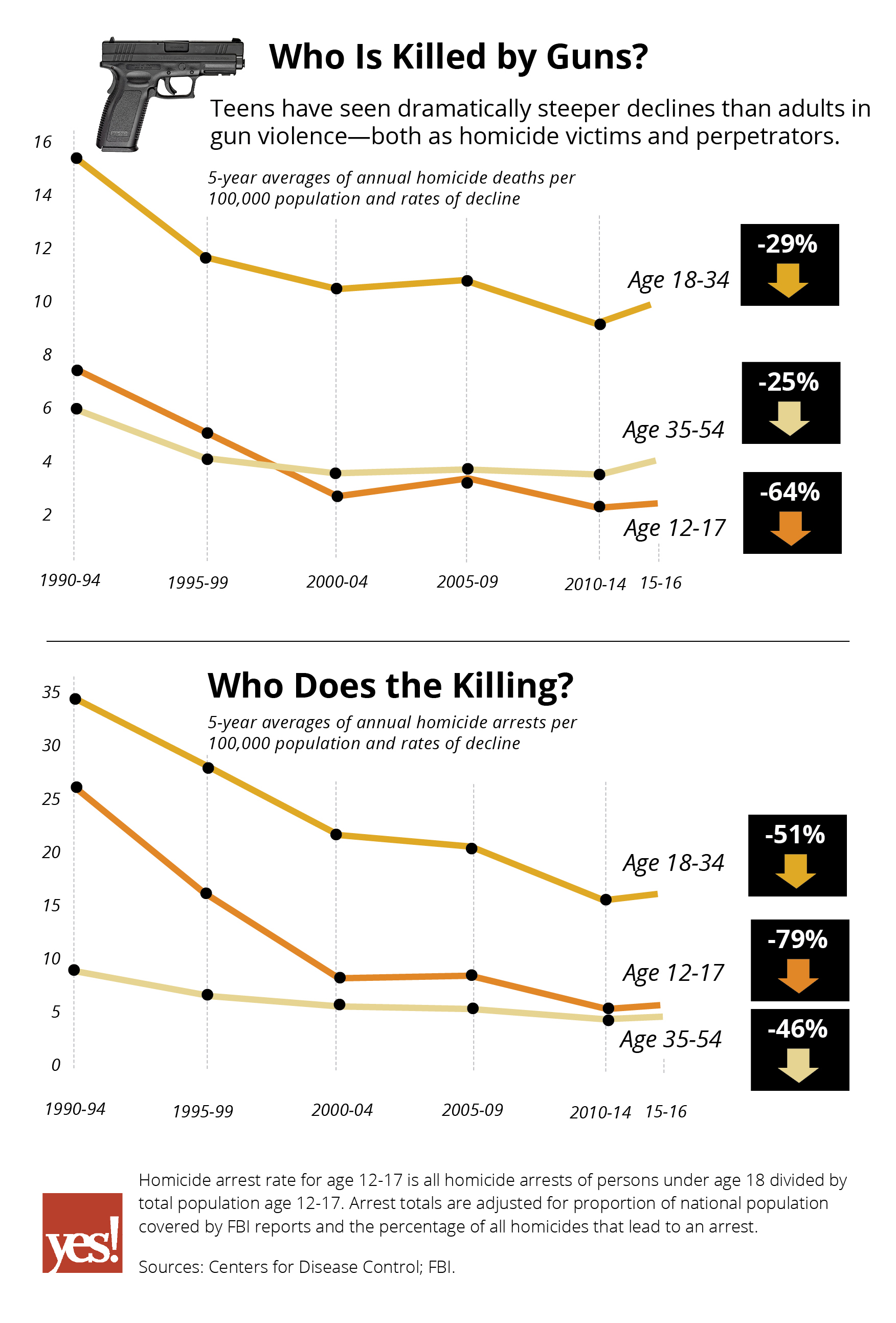

And that is happening. There has been an astonishing 25-year reduction in gun violence and homicide among youth (see charts). This puts high schoolers in a unique position to challenge today’s narrow political discourse.

Those young people who in previous generations might have reached for a gun are doing that far less often in the 2000s. The trend is the same for other negative behaviors: Those who might have dropped out of school are staying in. The criminal element is going straight. Their homophobic and xenophobic cohorts have dwindled, and most youth are opting for tolerance and integration. Fewer young women are experiencing unplanned pregnancies.

Today’s Millennials and younger Generation Zers are living those changes, and they’re adding up. In New York City and Los Angeles, a racially diverse generation of middle- and high-school students reduced gun homicides from a total 447 in 1990 to 42 in 2016. Across the country, school-age teens 12-17 show a drop in gun homicide rates more than double that of other ages. Today, they’re actually safer from gun homicide than their parents.

Old theories no longer explain youth behaviors. Gun control laws are weaker and youth poverty remains high. Older generations are displaying more negative behaviors, such as drug abuse and crime. Social programs have been cut back, higher education costs have skyrocketed, and popular culture has become more explicit. And yet, Millennials and Gen Z are showing dramatic improvements in every locale (teenage crime rates are down 70 percent in Idaho, and gun killings are down 65 percent in Texas, for example). They are most pronounced among young women, in cities (especially global ones like New York City and Los Angeles) and in areas where immigrants make up a large share of the youth population.

Today’s youth could be described as “post-sociology.” That is, as a generation, they no longer act like the popular stereotype and conventional social-science construct of the risk-taking, impulsive teenager. The Millennial/Gen Z signature move seems to be this: “solve” social problems not through political reform but by reducing those problems to irrelevancy.

Teenagers killed by gun haven’t disappeared from New York City and L.A., but they’re down 91 percent over the last generation. Births by teen mothers still happen there, but they’ve fallen from 40,000 a year to 9,000. Youths still drop out of school, but just one-third as many as in the past.

There remains the occasional young shooter whom the commentariat misperceives as the new poster child for gun violence. But in looking at the generations as a whole, Millennials/Zers are contributing to large, overall reductions in American gun violence—even if legislators turn their backs on legal reforms pushed by student movements.

I believe positive youth trends are a massive counter-reaction by younger people against the disastrous increases in addiction, crime, and imprisonment that their parents’ generation is suffering. Pundits marvel at the size of the women’s marches and the student uprising against guns. They point to how Millennials paved the way for gay rights not through legislative action, but by normalizing homosexuality as routine. Sexual harassment is going the same way, although slowly.

Statistical and survey evidence suggest enhanced global interconnectedness among today’s youth is yielding a revolution in behaviors and attitudes.

The revolution among younger Millennials and Gen Zers only occasionally resembles the kind of policy-manifesto, demand-specific political movement older generations recognize. The young are not trapped in age-old talking points and battles; their startling behavior improvements are largely the product of the unique interconnections modern technology and evolving tolerance are making available.

The real action is at the hidden, personal network level, where today’s young can freely access the most positive aspects of worldwide diversity. These interconnections may be more intense in larger cities where there are more personal contacts and closer interactions with more diverse populations, plus a broader array of services. But online connectivity augments those contacts and facilitates them almost everywhere in the country, helping to reverse the old stereotypes of self-obsessed, danger-seeking adolescence and isolated, troubled people. New sciences will have to shift to understand this evolution.

We need young people’s help. Adults’ ideas to reduce gun violence have not worked. Children and teenagers suffer the same proportions of gun fatalities in states with high age limits for gun purchases as in those without; shootings occur in schools that have armed guards (as was the case in Parkland, Florida), schools with advanced security technology, and so on.

Experience shows more armed grownups in schools is definitely not the answer. A number of “school shootings” in the last year alone actually involved guns brought into schools by teachers, a teacher’s partner, a principal, and a police officer.

Examination shows that around 9 in 10 shootings in schools don’t specifically target schools; they involve society’s problems spilling into schools. As many public shooters (including mass shooters) are over age 40 as are under 25. Businesses and workplaces have many more shootings, and home—not school—are by far the most likely place for a child to suffer a gun homicide. Adding 750,000 to 1 million more guns in schools (the math behind the Trump/NRA proposal to arm six to eight teachers per school) would only multiply gun problems.

It is understandable that the “Never Again” student movement born of a horrific school shooting is focused on schools and the particular 20-year-old shooter. But the two dozen or so deadly school shootings every year cannot be addressed without confronting the thousands of gun homicides that occur nowhere near a school.

Political leaders should not get to take the easy way out by narrowly scapegoating young people and schools for America’s gun crisis. This sudden, new student movement can revolutionize America’s gun debate the same way its generation is changing the environment of gun violence if it challenges the broader culture.

Gun control advocates can work with Millennials’ and Zers’ strengths—not by slandering them as violent and demeaning them as helpless victims, and not just by temporarily championing them as energized advocates for established lobbies’ political agendas, but as a genuine representative of real change with something new to say.

------------------------------------------------------------------------

Mike Males is senior researcher for the Center on Juvenile and Criminal Justice based in San Francisco, CA.

|