Date: 2025-04-06 Page is: DBtxt003.php txt00003393

Intellectual Property

The business model is wrong

Academic paywalls mean publish and perish ... Academic publishing is structured on exclusivity, and to read them people must shell out an average of $19 per article.

Burgess COMMENTARY

Here is the feedback on this article:

I really enjoyed this article ... and the links to other material about the issue.It is time that ordinary people start to push back against the money profit business model that has been pushed by business schools for half a century. Exploiting people because you can is not my idea of a civilized society.

Thanks ... you have made an excellent case for something better.

Peter Burgess

Academic paywalls mean publish and perish ... Academic publishing is structured on exclusivity, and to read them people must shell out an average of $19 per article.

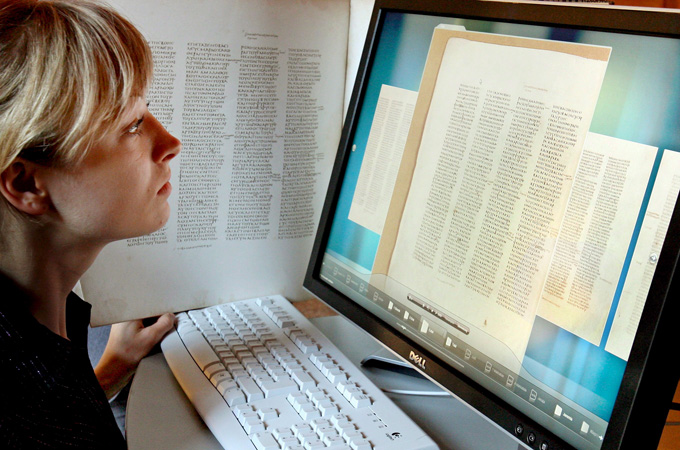

IMAGE Discussions of open access publishing have centred on whether research should be made free to the public [EPA]

On July 19, 2011, Aaron Swartz, a computer programmer and activist, was arrested for downloading 4.8 million academic articles. The articles constituted nearly the entire catalogue of JSTOR, a scholarly research database. Universities that want to use JSTOR are charged as much as $50,000 in annual subscription fees.

Individuals who want to use JSTOR must shell out an average of $19 per article. The academics who write the articles are not paid for their work, nor are the academics who review it. The only people who profit are the 211 employees of JSTOR.

Swartz thought this was wrong. The paywall, he argued, constituted 'private theft of public culture'. It hurt not only the greater public, but also academics who must 'pay money to read the work of their colleagues'.

For attempting to make scholarship accessible to people who cannot afford it, Swartz is facing a $1 million fine and up to 35 years in prison. The severity of the charges shocked activists fighting for open access publication. But it shocked academics too, for different reasons.

'Can you imagine if JSTOR was public?' one of my friends in academia wondered. 'That means someone might actually read my article.'

Academic publishing is structured on exclusivity. Originally, this exclusivity had to do with competition within journals. Acceptance rates at top journals are low, in some disciplines under 5 per cent, and publishing in prestigious venues was once an indication of one’s value as a scholar.

Today, it all but ensures that your writing will go unread. 'The more difficult it is to get an article into a journal, the higher the perceived value of having done so,' notes Katheen Fitzpatrick, the Director of Scholarly Communication at the Modern Language Association. 'But this sense of prestige too easily shades over into a sense that the more exclusively a publication is distributed, the higher its value.'

Discussions of open access publishing have centred on whether research should be made free to the public. But this question sets up a false dichotomy between 'the public' and 'the scholar'. Many people fall into a grey zone, the boundaries of which are determined by institutional affiliation and personal wealth. This category includes independent scholars, journalists, public officials, writers, scientists and others who are experts in their fields yet are unwilling or unable to pay for academic work.

This denial of resources is a loss to those who value scholarly inquiry. But it is also a loss for the academics themselves, whose ability to stay employed rests on their willingness to limit the circulation of knowledge. In academia, the ability to prohibit scholarship is considered more meaningful than the ability to produce it.

'Publish and perish'

When do scholars become part of 'the public'? One answer may be when they cannot afford to access their own work. If I wanted to download my articles, I would have to pay $183. That is the total cost of the six academic articles I published between 2006 and 2012, the most expensive of which goes for 32£, or $51, and the cheapest of which is sold for $12, albeit with a mere 24 hours of access.

'The more difficult it is to get an article into a journal, the higher the perceived value of having done so.' - Katheen FitzpatrickSince I receive no money from the sale of my work, I have no idea whether anyone purchased it. I suspect not, as the reason for the high price has nothing to do with making money. JSTOR, for example, makes only 0.35 per cent of its profits from individual article sales. The high price is designed to maintain the barrier between academia and the outside world. Paywalls codify and commodify tacit elitism.

In academia, publishing is a strategic enterprise. It is less about the production of knowledge than where that knowledge will be held (or withheld) and what effect that has on the author's career. New professors are awarded tenure based on their publication output, but not on the impact of their research on the world - perhaps because, due to paywalls, it is usually minimal.

'Publish or perish' has long been an academic maxim. In the digital economy, 'publish and perish' may be a more apt summation. What academics gain in professional security, they lose in public relevance, a sad fate for those who want their research appreciated and understood.

Many scholars hate this situation. Over the last decade, there has been a push to end paywalls and move toward a more inclusive model. But advocates of open access face an uphill battle even as the segregation of scholarship leads to the loss of financial support.

In the United States, granting agencies like the National Science Foundation have come under attack by politicians who believe they fund projects irrelevant to public life. But by denying the public access to their work, academics do not allow taxpayers to see where their money is spent. By refusing to engage a broader audience about their research, academics ensure that few will defend them when funding for that research is cut.

Tyranny of academic publishers

One of the saddest moments I had in graduate school was when a professor advised me on when to publish. 'You have to space out your articles by when it will benefit you professionally,' he said, when I told him I wanted to get my research out as soon as possible. 'Don't use up all your ideas before you’re on the tenure track.' This confused me. Was I supposed to have a finite number of ideas? Was it my professional obligation to withhold them?

What I did not understand is that academic publishing is not about sharing ideas. It is about removing oneself from public scrutiny while scrambling for professional security. It is about making work 'count' with the few while sequestering it from the many.

Soon after the arrest of Aaron Swartz, a technologist named Gregory Maxwell dumped over 18,000 JSTOR documents on the torrent website The Pirate Bay. 'All too often journals, galleries and museums are becoming not disseminators of knowledge - as their lofty mission statements suggest - but censors of knowledge, because censoring is the one thing they do better than the internet does,' he wrote.

He described how he had wanted to republish the original scientific writings of astronomer William Herschel where people reading the Wikipedia entry for Uranus could find them. In the current publishing system, this constitutes a criminal act.

Maxwell and Swartz were after a simple thing: for the public to engage with knowledge. This is supposed to be what academics are after too. Many of them are, but they are not able to pursue that goal due to the tyranny of academic publishers and professional norms that encourage obsequiousness and exclusion.

The academic publishing industry seems poised to collapse before it changes. But some scholars are writing about the current crisis. Last month, an article called 'Public Intellectuals, Online Media and Public Spheres: Current Realignments' was published in the International Journal of Politics, Culture and Society.

I would tell you what it says, but I do not know. It is behind a paywall.

Sarah Kendzior is an anthropologist who recently received her PhD from Washington University in St Louis.

The views expressed in this article are the author's own and do not necessarily reflect Al Jazeera's editorial policy.

Source: Al Jazeera

http://pastebin.com/cefxMVAy Aaron Swartz July 2008, Eremo, Italy Information is power. But like all power, there are those who want to keep it for themselves. The world’s entire scientific and cultural heritage, published over centuries in books and journals, is increasingly being digitized and locked up by a handful of private corporations. Want to read the papers featuring the most famous results of the sciences? You’ll need to send enormous amounts to publishers like Reed Elsevier. There are those struggling to change this. The Open Access Movement has fought valiantly to ensure that scientists do not sign their copyrights away but instead ensure their work is published on the Internet, under terms that allow anyone to access it. But even under the best scenarios, their work will only apply to things published in the future. Everything up until now will have been lost. That is too high a price to pay. Forcing academics to pay money to read the work of their colleagues? Scanning entire libraries but only allowing the folks at Google to read them? Providing scientific articles to those at elite universities in the First World, but not to children in the Global South? It’s outrageous and unacceptable. “I agree,” many say, “but what can we do? The companies hold the copyrights, they make enormous amounts of money by charging for access, and it’s perfectly legal — there’s nothing we can do to stop them.” But there is something we can, something that’s already being done: we can fight back. Those with access to these resources — students, librarians, scientists — you have been given a privilege. You get to feed at this banquet of knowledge while the rest of the world is locked out. But you need not — indeed, morally, you cannot — keep this privilege for yourselves. You have a duty to share it with the world. And you have: trading passwords with colleagues, filling download requests for friends. Meanwhile, those who have been locked out are not standing idly by. You have been sneaking through holes and climbing over fences, liberating the information locked up by the publishers and sharing them with your friends. But all of this action goes on in the dark, hidden underground. It’s called stealing or piracy, as if sharing a wealth of knowledge were the moral equivalent of plundering a ship and murdering its crew. But sharing isn’t immoral — it’s a moral imperative. Only those blinded by greed would refuse to let a friend make a copy. Large corporations, of course, are blinded by greed. The laws under which they operate require it — their shareholders would revolt at anything less. And the politicians they have bought off back them, passing laws giving them the exclusive power to decide who can make copies. There is no justice in following unjust laws. It’s time to come into the light and, in the grand tradition of civil disobedience, declare our opposition to this private theft of public culture. We need to take information, wherever it is stored, make our copies and share them with the world. We need to take stuff that's out of copyright and add it to the archive. We need to buy secret databases and put them on the Web. We need to download scientific journals and upload them to file sharing networks. We need to fight for Guerilla Open Access. With enough of us, around the world, we’ll not just send a strong message opposing the privatization of knowledge — we’ll make it a thing of the past. Will you join us? Aaron Swartz July 2008, Eremo, Italy