Date: 2024-09-27 Page is: DBtxt003.php txt00011360

Impact Analysis

Mergers and Acquisitions

The 2016 acquisition of LinkedIn by Microsoft

Burgess COMMENTARY

Peter Burgess

I'd like to connect with you on non-GAAP accounting

You probably heard Microsoft's announcement that it was acquiring LinkedIn. One of the possible reasons that LinkedIn decided to sell is explored in this Andrew Ross Sorkin column from earlier in the week. You see, LinkedIn's love of stock compensation means that it also loves not including that compensation in its EBITDA calculations:

[D]espite all the headlines about growth and profits, LinkedIn has been a money-losing operation for the last two years.

You wouldn’t know that if you only glanced at LinkedIn’s news releases. That’s because LinkedIn steers investors to focus on what’s known as its adjusted Ebitda, or non-GAAP earnings. The company purposely strips out the cost of stock-based compensation, which has the effect of turning losses into gains. LinkedIn paid out $510 million in stock-based compensation last year; over the last two years, that stock-based compensation represented a whopping 96 percent of operating income, or 16 percent of revenue, according to [Mark] Mahaney [an RBC analyst]. Companies like Google, Amazon and Facebook paid out about 15 percent of operating income, or well under 10 percent of revenue.

LinkedIn justifies the practice by saying that stock-based compensation “is noncash in nature” and that excluding it from its earnings calculation provides “meaningful supplemental information regarding operational performance and liquidity.”

Prior to Microsoft's announcement, LinkedIn's stock price had been on quite a downslide and because the company compensates with stock, it could've seen a big exodus of employees. Which makes sense because the market already had made up its mind about LinkedIn's accounting:

Mr. Mahaney, the RBC analyst, said the use of so much stock-based compensation was a negative signal. “There are a variety of ways to look at this issue, but our general bias is that the lower the dependence on stock-based compensation, the higher the quality of the P&L,” he wrote in a report in April, using shorthand for the income statement.

LinkedIn, Twitter, Yahoo and Alibaba, which “have the most dependence on stock-based compensation,” also have results “of relatively lower quality,” Mr. Mahaney said.

Here's what's interesting. Sorkin thinks that if LinkedIn would've included stock comp expense in its press releases, investors would've seen that they were losing money and the stock would've gone down. But by excluding stock compensation from its EBITDA calculations, LinkedIn helped investors identify their company as one with lower quality financial reporting and the stock went down anyway. Would investors have made different decisions if LinkedIn had reported EBITDA instead of adjusted EBITDA? Because Facebook and other companies recently stopped excluding stock compensation from their EBITDA reporting, Sorkin thinks so:

It is not hard to believe that LinkedIn, barring this deal with Microsoft, would have soon been using the more realistic version of its earnings — and, in so doing, reporting more losses. The company certainly deserves credit for building a global network with 430 million users and becoming a household name. But absent this accounting method, uglier headlines would have dragged down the stock price even further, along with the morale of all those employees whose incomes were dependent on it.

I'm not so sure. If you believe markets are efficient, then wasn't LinkedIn's stock price already appropriate? Does ditching one non-GAAP metric (adjusted EBITDA) for another (plain ol' EBITDA) really give investors better information? It seems to me that the market already knew that LinkedIn liked to paint a rosier picture than its peers and adjusted accordingly. And then, Microsoft to the rescue!

Elsewhere in LinkedSoft: LinkedIn’s Autonomy Under Microsoft May Not Endure

One Unspoken Reason Behind the Microsoft-LinkedIn Deal

Andrew Ross Sorkin Andrew Ross Sorkin DEALBOOK JUNE 13, 2016

LinkedIn’s Manhattan newsroom. Some investors, including Warren Buffett, are critical of excluding stock-based compensation from earnings calculations. Credit Hiroko Masuike/The New York Times “Let me explain why.”

Jeff Weiner, LinkedIn’s chief executive, wrote a lengthy memorandum to his employees Monday morning, ticking off a list of reasons behind the surprise decision to sell the company to Microsoft for $26.2 billion: Most important, he said, was the heft that Microsoft gives LinkedIn “to control our own destiny.”

But there may have been another reason that he left unspoken.

That would be the company’s struggling stock price and its reliance — some might say overreliance — on stock-based compensation.

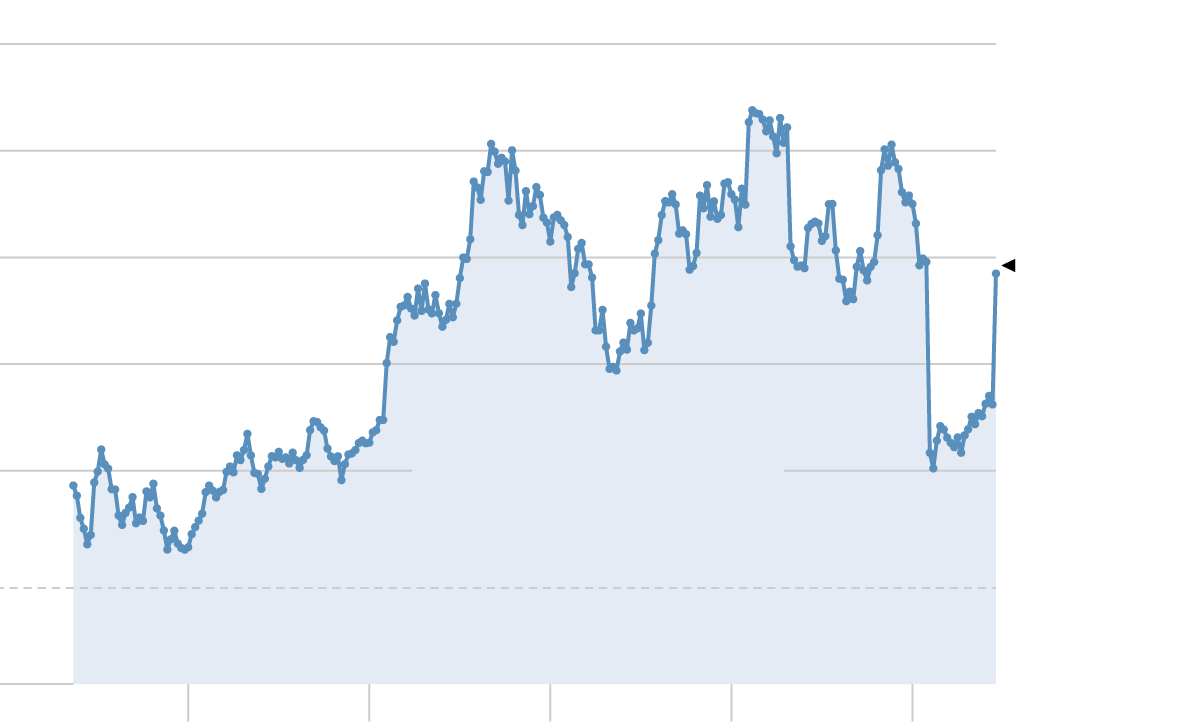

On one grim day in early February, LinkedIn’s stock price plummeted more than 40 percent after it forecast weaker-than-expected growth for the year. The share price had hovered at $225 at the beginning of 2016; a month later it briefly got close to $100.

The rapid devaluation has posed more than just a problem for investors. LinkedIn’s employees are paid largely in stock, and therein lies the rub: Around the company’s new 26-story skyscraper that opened in downtown San Francisco in March, as well as the corporate headquarters in Mountain View, Calif., there have been persistent whispers about whether LinkedIn could retain its top talent as the marketplace clobbered their incomes.

Among Silicon Valley companies, “LinkedIn is among the most aggressive in using share-based compensation — there is no question about that,” Mark Mahaney, a veteran technology analyst at RBC Capital Markets, said in an interview on Monday. “If the stock had stayed down, it would have seen employee churn.”

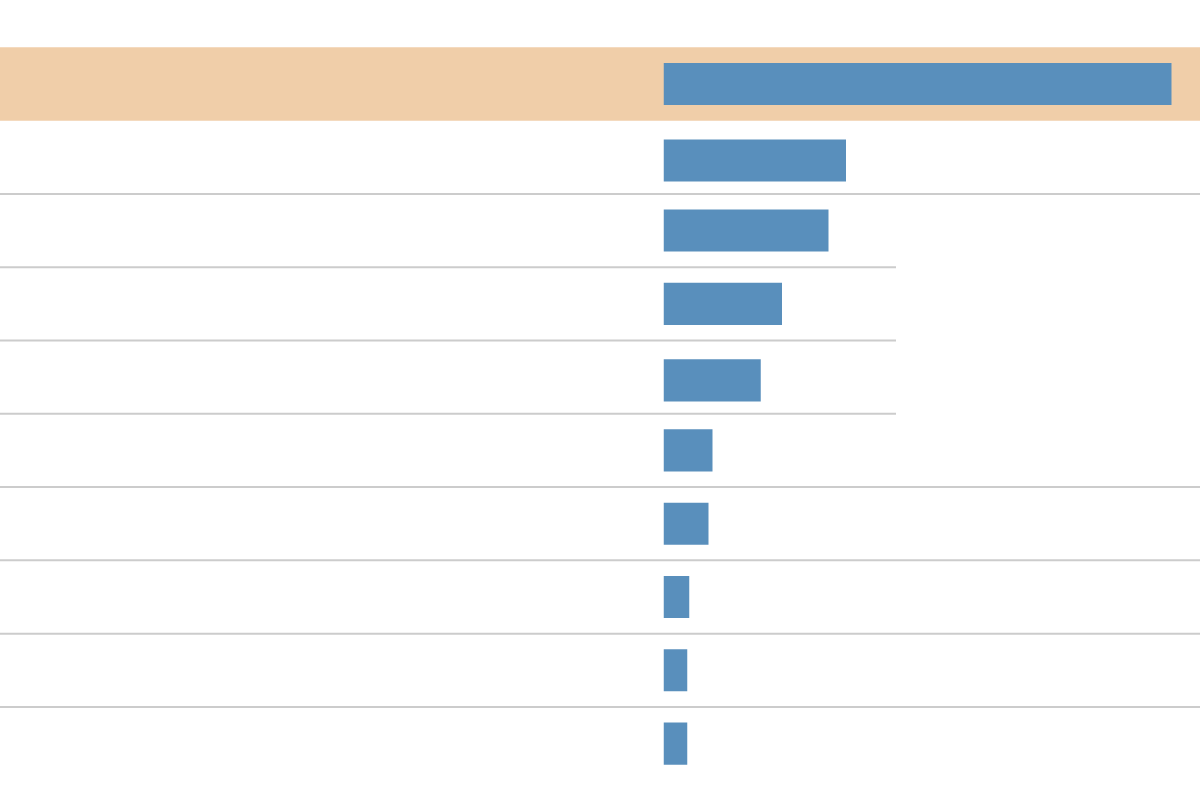

Microsoft’s Biggest Deal

In its biggest acquisition ever, Microsoft announced that it would buy the social networking site Linkedin for $26.2 billion in cash. LinkedIn’s share value rose nearly 50 percent on the news.

Mr. Weiner — who took over as LinkedIn’s chief in 2009, succeeding Reid Hoffman, the founder — has done a tremendous job in the past years building the company’s business, which is primarily about helping people connect to one another for employment and conduct business-oriented social networking. But despite all the headlines about growth and profits, LinkedIn has been a money-losing operation for the last two years.

You wouldn’t know that if you only glanced at LinkedIn’s news releases. That’s because LinkedIn steers investors to focus on what’s known as its adjusted Ebitda, or non-GAAP earnings. The company purposely strips out the cost of stock-based compensation, which has the effect of turning losses into gains. LinkedIn paid out $510 million in stock-based compensation last year; over the last two years, that stock-based compensation represented a whopping 96 percent of operating income, or 16 percent of revenue, according to Mr. Mahaney. Companies like Google, Amazon and Facebook paid out about 15 percent of operating income, or well under 10 percent of revenue.

LinkedIn justifies the practice by saying that stock-based compensation “is noncash in nature” and that excluding it from its earnings calculation provides “meaningful supplemental information regarding operational performance and liquidity.”

But investors like Warren E. Buffett have been highly critical of the practice. “It has become common for managers to tell their owners to ignore certain expense items that are all too real,” Mr. Buffett wrote in his annual report published this year. Stock-based compensation, he said, “is the most egregious example. The very name says it all: ‘compensation.’ If compensation isn’t an expense, what is it? And, if real and recurring expenses don’t belong in the calculation of earnings, where in the world do they belong?”

Mr. Buffett also criticized analysts who “play their part in this charade, too, parroting the phony, compensation-ignoring ‘earnings’ figures fed them by managements.”

In April, Facebook, which also used to steer investors to use adjusted-Ebitda earnings numbers that also excluded the cost of stock-based compensation, announced that it was changing its policy. “Stock-based compensation plays an important role in how we compensate our employees, and therefore we view it as a real expense for the business,” David Wehner, Facebook’s chief financial officer, said in an earnings call.

CNBC By CNBC 4:20 Microsoft & LinkedIn C.E.O.s on Deal Video Microsoft & LinkedIn C.E.O.s on Deal Satya Nadella of Microsoft and Jeff Weiner of LinkedIn said that they began talking in earnest about their $26.2 billion cash deal in February. By CNBC on Publish Date June 13, 2016. Photo by CNBC. Watch in Times Video » Embed ShareTweet

Facebook’s decision to change its practice was seen as a shot across the bow at companies like LinkedIn. Other companies, like Amazon and Intel, also account for stock compensation as an expense.

It is not hard to believe that LinkedIn, barring this deal with Microsoft, would have soon been using the more realistic version of its earnings — and, in so doing, reporting more losses. The company certainly deserves credit for building a global network with 430 million users and becoming a household name. But absent this accounting method, uglier headlines would have dragged down the stock price even further, along with the morale of all those employees whose incomes were dependent on it.

Mr. Mahaney, the RBC analyst, said the use of so much stock-based compensation was a negative signal. “There are a variety of ways to look at this issue, but our general bias is that the lower the dependence on stock-based compensation, the higher the quality of the P&L,” he wrote in a report in April, using shorthand for the income statement.

LinkedIn, Twitter, Yahoo and Alibaba, which “have the most dependence on stock-based compensation,” also have results “of relatively lower quality,” Mr. Mahaney said.

Other stock analysts took note that Microsoft, which includes stock-based compensation in its non-GAAP earnings calculation, made a point on Monday of saying that the combined company would follow Microsoft’s practice. In other words, from now on, LinkedIn employees will no longer enjoy results that looked rosier because their stock-based compensation was not figured in. (Though as a unit of Microsoft, it is unclear whether their results will even be broken out for investors to see).

A spokeswoman for LinkedIn declined to comment, pointing to comments Mr. Weiner made in a memo he sent to employees.

In that memo and in conversations with employees on Monday, Mr. Weiner said that the impetus for the deal was not about the stock, but was more about a larger trend that he and LinkedIn’s founder, Mr. Hoffman, had noticed late last year: The biggest companies in the Valley — Facebook, Google and a few others — had pulled way ahead of the pack by increasing and earning the largest valuations, making it harder for smaller tech companies to attract top talent. Ultimately, they decided that LinkedIn was in a better competitive position if it, ahem, linked in with Microsoft.

A version of this article appears in print on June 14, 2016, on page B1 of the New York edition with the headline: An Unspoken Reason Behind the LinkedIn Sale. Order Reprints| Today's Paper|Subscribe