Date: 2025-01-15 Page is: DBtxt003.php txt00012223

Wealth

The burden of great wealth

WEALTH CULTURE ... Inside the Homes of Britain's Modern Aristocrats ... Spoiler: Death and taxes come to us all.

Burgess COMMENTARY

I like this essay published by Bloomberg ... but the messaging should not be taken seriously. All media outlets indulge in publishing material that will be attractive to the readers they want, and in the case of Bloomberg, they are interested in readers who are wealthy ... and most everything about this essay will sit well with the wealthy. I like this essay, not because I am wealthy, but because I do like history and I do like beautiful things ... and this essay documents some interesting history and some beautiful houses and furnishings. I don't consider the lessons of history and the way wealth has been accumulated and taxed in the past should be used as a template of how a modern economy should indulge the present generation of wealthy people. There is a lot of talk about the sharing economy ... meaning ordinary people sharing access to all sorts of ordinary things that they otherwise would not be able to buy and use ... but I want to argue that the modern cohort of high income and high net worth individuals should be sharing much more of their income and wealth than they do, so that ordinary people would be just a little bit better off. The extraction of wealth by powerful people from working people to maximise profit and wealth accumulation for investors has been the root cause of income and wealth equality for a very long time.

Peter Burgess

WEALTH CULTURE ... Inside the Homes of Britain's Modern Aristocrats ... Spoiler: Death and taxes come to us all.

“An aristocracy in a republic,” observed the writer Nancy Mitford, “is like a chicken whose head has been cut off; it may run about in a lively way, but in fact it is dead.”

The new book Great Houses, Modern Aristocrats by Vanity Fair contributor James Reginato has ostensibly been created to refute Mitford’s claim.

“Though many of these subjects were hardly young,” Reginato writes in the book’s introduction, “I came to see how modern they were, in fact, as they came to adapt themselves to changing times and changing concepts of country-house ownership.”

Great Houses, Modern Aristocrats by James Reginato, Rizzoli New York, 2016 ... Source: Rizzoli New York

That doesn’t quite come across in the book’s coverage of 16 magnificent, centuries-old houses and their owners. Reginato recounts struggling scions forced to open their homes to endless tour groups and a woman with more titles than the Queen of England who moved from a Georgian mansion into a farmhouse. Another homeowner, John Crichton Stuart, the 7th Marquess of Brute, was unable to sustain Dumfries House, an 18th century Palladian villa in Ayrshire, Scotland, in addition to his other estate, a gothic-revival mansion set on 38,000 acres; only the intervention of Charles, Prince of Wales, kept the house and its interiors from hitting the market. “The auction was called off,” Reginato writes. “And several truckloads of treasure already en route to London were returned home.”

2012.022_Lord March - Goodwood_CS17_F17 001 ... The Large Library at Goodwood House in West Sussex.Photographer: Jonathan Becker

But would that really have been so bad?

From the perspective of a Downton Abbey-loving public, these lords, ladies, marquesses, and earls are engaged in a noble, perhaps even quixotic struggle to maintain the brilliance and beauty of their families’ estates. From a more republican perspective, Reginato has documented a small group of people yoked by their own volition to a collection of unsustainably large mansions. Few would pity the great-granddaughter of an investment banker who struggles to maintain her family vacation home on Long Island; take a broad view, and the plight of these “modern aristocrats” isn’t so different. They’ve just been doing it longer.

Luggala, a house in County Wicklow, Ireland, owned by an heir to the Guiness brewing fortune.Photographer: Jonathan Becker

The majority of the houses Reginato features are in the United Kingdom, and the bulk of those houses’ owners belong to a landowning class whose money and power began to wane with the onset of the industrial revolution. By the time the World War I rolled around and the sons of England’s landed gentry were massacred (1,157 Eton graduates died in battle from 1914 to 1918), the great houses of U.K. were in a state of disrepair. Only canny moves such as advantageous marriages kept the houses running (Blenheim, the colossal mansion near Oxford, was “saved” by a loveless marriage between the 9th Duke of Marlborough and the massively wealthy American heiress Consuelo Vanderbilt).

Even the Rothschild family, whose banking interests made them relatively immune to the British economy’s changing landscape, gave up Waddesdon Manor, their spectacularly ornate house in Buckinghamshire. “After the Second World War,” writes Reginato, “Waddesdon became too much even for a Rothschild to maintain.” The house, its contents, and 165 acres were bequeathed to the National Trust.

Waddesdon Manor, which the Rothschild family donated to the National Trust.Photographer: Jonathan Becker

The list goes on. The Fiennes family, who has owned Broughton Castle since 1377, lives in the “private side” of the house; the rest is open to the public, which pays a 9 pound entrance fee. Members of the family, Reginato writes, occasionally man the cash register at the house’s gift shop.

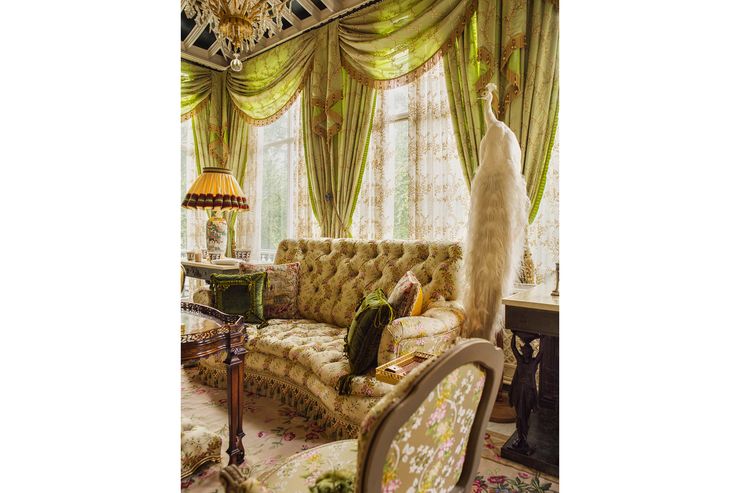

Lord Edward Manners, the second son of the 10th Duke of Rutland, inherited a manor house in Derbyshire; he turned one of its outbuildings into an inn (“The Peacock”) and admits tourists into the staterooms of the manor house in the summer. Reginato notes that “while some might see taking over a large and old estate as a burden, Manners calls it ‘a wonderful lifetime project.”

All these people are aristocrats, in other words, but they are not a reigning class. Hedge fund managers, in contrast, don’t have to charge an entrance fee to their living rooms.

2010.034_The Duchess of Marlborough_CS03_F05 001 ... The Third State Room at Blenheim Palace.Photographer: Jonathan Becker

There are some exceptions.

Two homes owned by the immensely wealthy Cavendish family are featured in Great Houses. One of the residences is a relatively modest cottage once occupied by the late Dowager Duchess of Devonshire, who left her 297-room Chatsworth House when her son took over her husband’s dukedom. Reginato quotes her as being delighted by the cottages’ petite charms.

“The luxury of having everything so small—it’s simply amazing!” the Duchess says. The other Cavendish house in the book is Lismore Castle in County Waterford, Ireland, which Reginato euphemistically describes as the family's 'extra home.'

The late Deborah Vivien Freeman-Mitford Cavendish, Dowager Duchess of Devonshire, in her cottage, which is known as The Old Vicarage.Photographer: Jonathan Becker

Perhaps the most magnificent of the Great Houses is owned by royalty of a more recent sort. Dudley House, the London residence of the Qatari Sheikh Hamad bin Abdullah Al-Thani, spans about 44,000 square feet and includes 17 bedrooms and a 50-foot-long ballroom; its estimated value is about $400 million. When Queen Elizabeth visited the residence, she reportedly remarked drily that it '… makes Buckingham Palace look rather dull.'

An interior of Dudley House in central London.Photographer: Jonathan Becker

And while this might be a backhanded compliment from one royal to another, it speaks to the fundamental truth that the perception of “true” aristocracy in the European mold has come to imply a sort of faded glory, the likes of which is seen in page after glossy page of Reginato’s beautiful book. What is conveniently forgotten, amid this valorization and nostalgia for an ancient, gracious time gone by, is that when each of the featured homes were constructed, they were the McMansions of their day: gaudy, ostentatious piles meant to telegraph wealth, power, and prestige. Similarly, today's true aristocrats build houses for the same reasons; it's just that our nobility's titles are awarded by a board of directors, not the queen.