Date: 2025-12-24 Page is: DBtxt003.php txt00012815

The Trump Presidency

Learning from History

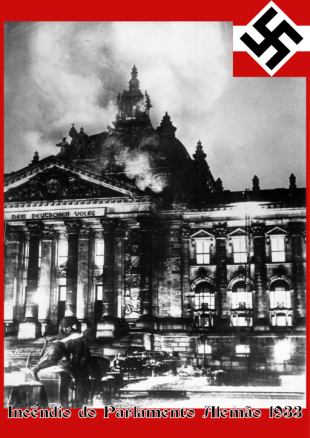

Could There Be an American Reichstag Fire? Don't Underestimate Trump ... February 27 is the anniversary of the fire that destroyed the Reichstag and gave Hitler a pretext to seize total power. Could this happen in the U.S.

Burgess COMMENTARY

Peter Burgess

Photo Credit: By Eugenio Hansen, OFS (Own work) [CC BY-SA 3.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0)], via Wikimedia Commons

Just cannot believe a judge would put our country in such peril. If something happens blame him and the court system. — Donald Trump, tweet, February 5

On the night of February 27, 1933, less than a month after Adolf Hitler became chancellor of Germany, fire gutted the central chamber of the Reichstag in Berlin, the nation’s parliament building. To this day, historians are still debating whether it was the work of a lone arsonist, the Dutch communist Marinus van der Lubbe, who was caught at the scene and soon confessed, or as journalist William L. Shirer later asserted in his classic Rise and Fall of the Third Reich, that there was “enough evidence to establish beyond a reasonable doubt that it was the Nazis who planned the arson and carried it out for their own political ends.”

But of one thing there was no doubt.

Within hours of the fire, hundreds of people were arrested and put in “protective custody” or sent to concentration camps, and the next morning (in the words of the Cambridge University historian Richard Evans), “the cabinet, which still had a non-Nazi majority, met to draw up an emergency decree that abrogated civil liberties across Germany. Signed by President Hindenburg the same day, it abolished freedom of speech, freedom of assembly and association, and freedom of the press, suspended the autonomy of federated states, such as Baden and Bavaria, and legalized phone-tapping, the interception of correspondence, and other intrusions.”

The decree was the first of two major measures that eliminated all institutional checks and gave Hitler absolute dictatorial powers. The second, passed a month later by the Reichstag, gave Hitler plenary power—the power to enact laws without any action by the parliament whatever. Quoting Evans again,

The Nazis used them to bludgeon their opponents into submission and their allies into compliance. By the summer of 1933 all opposition had been crushed, more than a hundred thousand Communists, Social Democrats, and other opponents of the Nazis had been sent to concentration camps, all independent political parties had been forced to dissolve themselves, and the Nazi dictatorship had been firmly established.

Could it happen here, as the historian Robert S. McElvaine of Millsaps College recently warned in the Huffington Post?

The odds are that it could not—not in the same way and certainly not to the same extent, despite Donald Trump’s megalomaniacal rhetoric and the radicals in his entourage. Trump has no global agenda, clings fanatically to no ideology, has no Weltanschauung, as Hitler had; his highest priority appears to be himself.

Nor is America in 2017 like Germany in 1933. The two cultures are vastly different and the technology that enabled Trump to gain political power is just as accessible to his opposition. It’s also likely, judging by his appellate court opinions, that Neil Gorsuch, Trump’s nominee to fill Antonin Scalia’s seat on the Supreme Court, will, despite his conservative leanings on issues like abortion, be faithful to the Constitution’s protections of the press and free speech; he will not eviscerate them. Moreover, in the view of CUNY historian Benjamin Hett, whose 2014 book Burning the Reichstag: An Investigation Into The Third Reich’s Enduring Mystery makes a strong case that the fire was a Nazi plot,

The media environment of today [he wrote me in an email]—with 24-hour cable news, the internet, Twitter, Facebook, etc., etc.—is so much more intrusive than in 1933 (and the federal government is so full of people who would be happy to leak incriminating information, not least in the intelligence services) that the Trump administration would have no chance of getting away with a deliberate terrorist attack as a pretext for a coup d’état. … The other important difference is that Trump is dramatically less popular than Hitler was in 1933 and there is significantly more pushback from the population to the things he is trying to do. Not that I wouldn’t put it past Trump and [Stephen] Bannon to be thinking about this kind of thing.

But as a refugee from Hitler (Class of ’41), I’m too much aware of the extent to which the Nazis were underestimated as low-class clowns and thugs until it was too late. Similarly, in the past election, the media, the pollsters, the Democrats and millions of other Americans, and not just the left, also underestimated Trump. In that context, I’m reminded of Hannah Arendt’s post-war observation that “in 1933, indifference was no longer possible. It was no longer possible even before that.”

Again there are troubling signs: the willingness of the Republican leadership in Congress to excuse or disregard Trump’s arrogant contempt for conflict of interest law and ethical standards and, worse, its spineless refusal to call for an independent investigation of the links between Trump and his people with the Kremlin; the administration’s draft memo on activation of “members of the state National Guard … in the apprehension, investigation and detention of aliens in the United States;” Trump’s call for “extreme vetting” of Muslim immigrants and the ill-disguised vilification of all Muslims as terrorists; the attacks on Mexican immigrants as criminals and rapists; the vastly broadened deportation criteria allowing the removal of virtually any undocumented immigrant, excepting only the “Dreamers” who were brought here as young children; the “America First” mantra, a favorite of isolationists, anti-Semites, and Nazi sympathizers in the years before Pearl Harbor; the invocation of “alternative facts” and other lapses into Orwellian Newspeak by Kellyanne Conway and the president’s other Trumpets; Trump’s attacks on the courts and “so-called” judges and on the media as the “enemy of the people.”

‘‘When you look at history,” warned John McCain, hardly a left-wing radical, “the first thing dictators do is shut down the press.” But maybe none of those things are as troubling or as apposite to Hitler’s Germany as the racism of some of the people around Trump and the instability, egomania, and psychological insecurity of Trump himself.

We’ve had periods of repression in the past, some supported by large segments of the population: the great Red Scare, accompanied by the Palmer Raids, the trial and execution of the anarchists Sacco and Vanzetti, and the rise of the second KKK, which at one time had between three and six million members, in the years immediately following the first World War; the McCarthyite witch hunts and the blacklists of the 1950s and 1960s; the enactment of the Patriot Act with its vastly broadened powers for government wire-tappers and other official snoopery after the September 11 attacks; the unconstitutional detention and internment of Japanese-Americans in the years immediately following Pearl Harbor. In the days after Trump’s election, one of his backers even cited the Korematsu decision upholding the interment, one of the most repugnant Supreme Court rulings in American history, as a possible legal precedent for registering all Muslims.

Even the extremists around Trump can’t organize anything like the Reichstag fire. But a shrewd terrorist group could well bomb some sensitive place in the United States—an attack on one or two of his hotels or golf clubs would probably drive Trump even beyond the fragile restraints of his already belligerently egocentric personality—and thereby provoke the larger war that extremists on both sides could well be itching for. Such a war—starting, say, with a retaliatory U.S. aerial attack on Tehran, or possibly a U.S. sanctioned Israeli attack on an Iranian facility—would quickly divert public attention from any of the administration’s scandals and open the doors to unprecedented repression of civil liberties. Could anyone count on Paul Ryan or Mitch McConnell or Jason Chaffetz to stand up to that?

Eric Larson, author of the highly regarded In the Garden of Beasts, about Berlin in the first years of the Hitler regime, has similar concerns, though he’s slightly more optimistic about Congress. Trump, he told me in answer to my emailed questions,

might try to use a terrorist event to pressure Congress into passing something akin to Hitler’s Enabling Act. Let’s hope that no such event occurs, and that if something does happen, that the GOP will at last stand up and say, “enough.” Republican senators and representatives are not idiots. They have to know this president is an authoritarian lunatic.

But would they have the political courage to act on that? Would the courts resist, as they resisted Trump’s travel ban, in a time of real national hysteria?

On those questions our most thoughtful civil libertarians are hardly reassuring. “In the past,” said Erwin Chemerinsky, the dean of the law school at the University of California Supreme at Irvine, wrote in an email, “the Supreme Court generally has done a poor job of standing up to the government’s restrictions of liberties during times of crisis.” Ira Glasser, executive director of the American Civil Liberties Union from 1978 to 2001, recited the “legion of examples,” from Dred Scott and Korematsu to the decisions upholding the anti-communist Smith Act, in which the Court found no violations of the right to free speech and association:

James Madison [Glasser said] predicted much of this unhappy history back in the 18th century, when he expressed skepticism that a Bill of Rights would work when it was most needed, calling it a “parchment barrier” during moments of fear and hysteria. Jefferson argued with him, saying that an independent court system would enforce constitutional limits, but although that has been true over extended periods of time, Madison had much the better argument during moments of madness and fear.

In his reductio ad absurdum response to my question, Richard Evans, the Cambridge historian, provided an ironic and hardly reassuring thought. “Fortunately the terrible terrorist attacks in Sweden and at Bowling Green,” he said, “did not prompt the president into assuming emergency powers.” But the international legal scholar John Shattuck, who’s been both a diplomat and university president in Central Europe, may have summarized the threat most succinctly. “Trump's security policies,” he said, “are creating greater insecurity and likelihood of terrorist attack, which in turn strengthens his hold on power. It's a vicious circle, similar to how Eastern European autocrats have used the refugee crisis to strengthen their hands.”

At bottom, there also remains this additional question: Not withstanding the obsessive lying, the Newspeak, and the malevolence and belligerence of people like Bannon and the Old South racism of men like Attorney General Jeff Sessions, is Trump focused or serious enough, and is his administration competent and organized enough, to consistently pursue any strategy? Still, it’s more than ironic that more than 80 years after the Reichstag Fire, some of us Hitler refugees, who could not have imagined such a thing even five years ago, are now looking to Angela Merkel and Germany as the most hopeful and stable outposts of Western democracy.

Peter Schrag, a longtime education writer and editor, is the co-author of When Europe Was a Prison Camp: Father and Son Memoirs, 1940-41 (Indiana University Press, 2015) and author of Paradise Lost: California's Experience, America's Future, and California: America's High-Stakes Experiment. He is a former editorial page editor of the Sacramento Bee.