Date: 2025-01-15 Page is: DBtxt003.php txt00013183

Urban Living / Cities

Congestion / Supply and Demand

America’s Cities Are Running Out of Room ... Everyone wants to live downtown, but only the rich can afford it. And it’s getting worse.

Burgess COMMENTARY

Peter Burgess

America’s Cities Are Running Out of Room

Everyone wants to live downtown, but only the rich can afford it. And it’s getting worse.

0:13

0:15

QuickTake: The American Dream of Home Ownership

QuickTake: The American Dream of Home Ownership

A shortage of homes for sale has bedeviled U.S. house hunters in recent years, so why don’t builders build more? One problem is that they’re running out of lots to build on—at least in the places that people want to live.

Cities that were sprawling before the Great Recession have begun to sprawl again. Space-constrained cities, meanwhile, have run out of room to build. That reality has spurred developers to focus on center-city neighborhoods where high-density building is allowed—and new units command exceedingly high prices.

At some point, said Issi Romem, chief economist at BuildZoom, vacant lots in desirable urban neighborhoods will run out. “If you have three days of rations left, you’ll be fine on day one, two, three,” said Romem, author of new research demonstrating home construction patterns. “On day 4, you have a problem.”

Historically, cities grew outward, as builders developed tracts on the periphery—then filled in the land between various developments over time. When these so-called expansive cities of the South and Southwest run out of infill land on which to build, developers simply pushed out further.

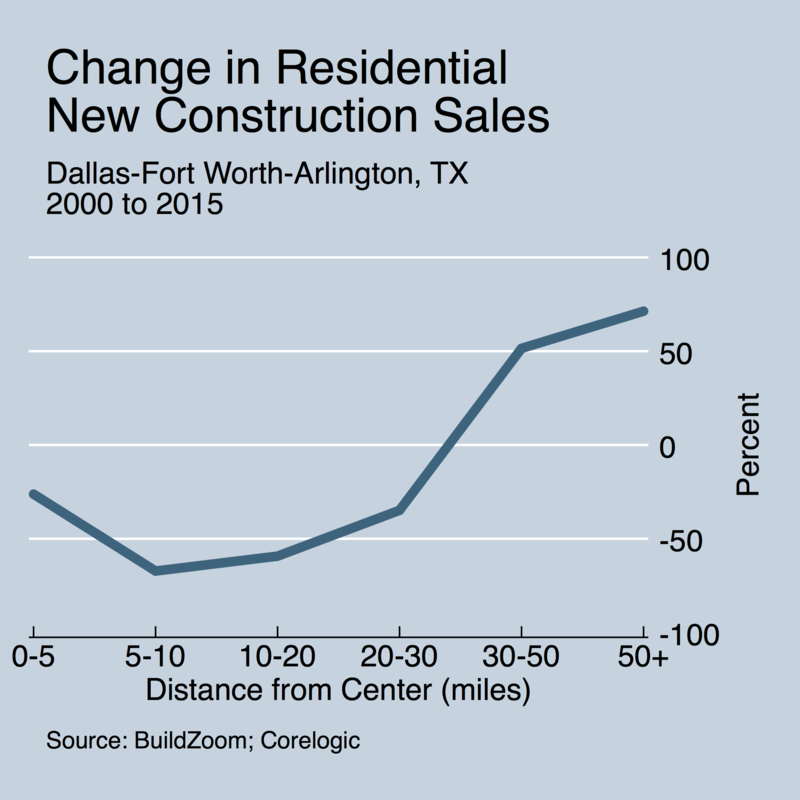

Some of these cities, like Austin and Nashville, have seen downtown boomlets. But more broadly, the building trends in those metros looks more like Dallas: Inside a 30-mile radius from the center of the city, new home sales decreased from 2000 to 2015. Outside the radius, though, sales are up by more than 50 percent. The same trend has played out to varying degrees in Phoenix, Atlanta, and San Antonio, among other cities.

In America’s most expensive cities, however, that dynamic has been turned inside out (or perhaps outside in). New construction trends in places like New York City have been tightly focused on downtown clusters where zoning rules permit high-density construction. These cities stopped expanding their geographic footprint decades ago, leaving builders to concentrate on finding buildable lots inside existing boundaries. As those lots became harder to find, land prices increase, reducing options for builders hoping to turn a profit. Developers building on pricey lots generally seek to offset land prices by building more densely, Romem said. In many cases, that means focusing on high-end apartments that offer better profit margins. The wealthiest residents are the only ones who can buy, and a vicious cycle is created.

Lately, there has been some give as oversupply of new high-end apartments forces landlords in New York and San Francisco to drop prices on expensive aeries. Still, the broader pattern continues to lean in the direction of higher rents.

What happens next depends on whether voters and their elected officials rewrite zoning rules to allow denser construction, said Romem, particularly in neighborhoods currently limited to single-family homes. Under current rules, he said, it’s unlikely new housing will get built at affordable prices, pushing city-dwellers into a game of musical chairs rigged to favor the rich.

“As long as these cities continue to do well economically, you’re going see poorer folks replaced by richer folks,” he said. “You’re going to read stories about teachers not being able to find place to live.”