Date: 2024-07-17 Page is: DBtxt003.php txt00013457

UK / Brexit / Capital Markets

London Stock Exchange

London's Shrinking Stock Market ... Smaller firms matter more than bagging giant IPOs like Aramco.

Burgess COMMENTARY

Peter Burgess

London's Shrinking Stock Market ... Smaller firms matter more than bagging giant IPOs like Aramco.

PHOTOGRAPHER: CHRIS JACKSON/GETTY IMAGES

Call it the curse of Brexit.

Worldpay Group Plc was the U.K.'s biggest initial public offering in 2015. Now the payments firm is set to be acquired and de-listed. Like ARM Holdings Plc, the pound's fall after Britain's vote to leave the European Union made the FTSE 100 company more vulnerable to a takeover.

Finding future home-grown champions will be a tougher and more important challenge for the City of London than bagging giant IPO candidates like Saudi Aramco.

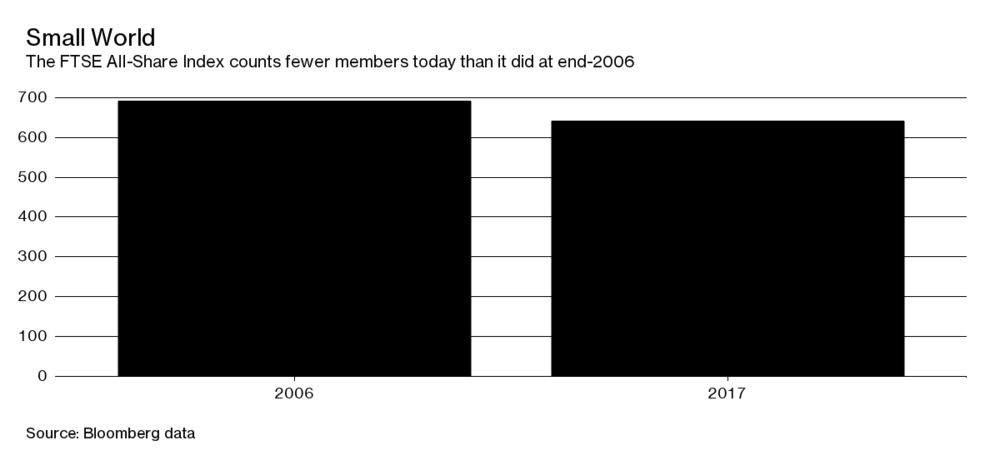

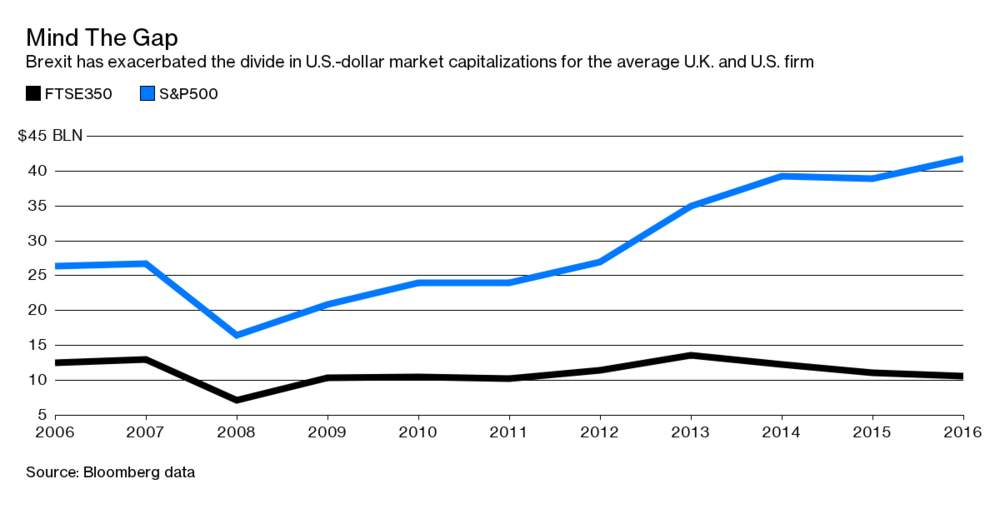

Waving farewell to prized businesses would be no bad thing if there was a pipeline of replacements. But the U.K.'s public markets are thinning out: the number of London-listed firms tracked by the FTSE All-Share Index has fallen to 642 from 692 in 2006, according to Bloomberg data. In dollar terms, the average U.K. firm's market value has been shrinking in recent years, a trend exacerbated by Brexit.

The U.K. is falling prey to de-equitization, something that has hit the U.S. particularly hard. There, the number of listed companies has fallen by about 50 percent in 20 years, according to Credit Suisse, reflecting a boom in mergers and a propensity for start-ups to stay private.

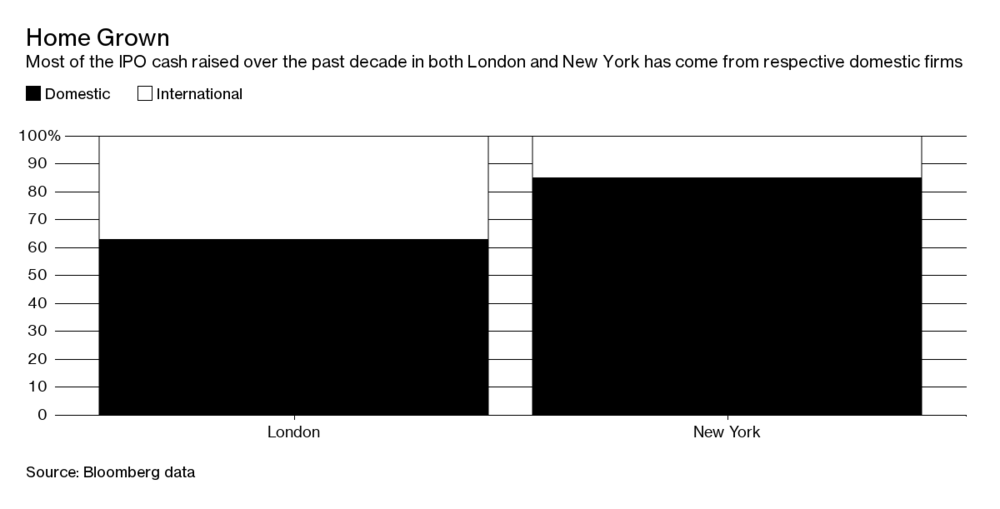

Fretting about whether London can attract global companies like Aramco looks like a distraction. Domestic listings, not foreign ones, account for the lion's share of U.K. IPOs over the past decade.

It is these firms that are either de-listing or, as small-business groups say, finding it harder to come to the market in the first place. That's why regulators need to look at whether smaller firms deserve a freer rein from rules that were designed with large global companies in mind.

Earlier this year, the Financial Conduct Authority reported investor grumblings over the size of late-stage venture capital fundraisings in the U.K., which are significantly smaller than in the U.S. U.K. technology companies are also 'disproportionately' vulnerable to takeovers compared with peers abroad, it said. Japan's SoftBank, for example, has in the space of a year bought ARM Holdings and poured cash into Improbable Worlds, a London-based virtual-reality start-up.

Efforts by the LSE to court small firms through the junior AIM market and the 'Elite' program to help businesses access investors are useful. But constructs like the recent partnership between Google owner Alphabet, Swiss drugmaker Novartis AG, institutional investors and European taxpayers show how public markets are being snubbed, as my colleague Chris Hughes has pointed out.

Leaving the single market will bring additional headaches for Britain if it raises the barriers to immigration and cuts off access to EU funds for venture capital.

The drum-beat for deregulation is therefore likely to get louder as policy makers search for ways to help more companies to access capital from the public markets. Britain's gold-plated regulatory regime goes beyond the EU's minimum requirements, and it could conceivably be changed without smashing years of rule harmonization.

On the other hand, the revolt among fund managers at proposals to bend the rules for Saudi Aramco shows how attached long-term investors are to the credibility of a premium London listing.

But there's still room to help smaller firms, and failure to do so would leave London's capital markets at risk of flunking their Brexit test.

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of Bloomberg LP and its owners.