Date: 2024-12-21 Page is: DBtxt003.php txt00013726

INDUSTRIAL SAFETY

TOXIC CHEMICALS IN THE HOUSTON AREA

Multi-part series by investigative journalists from the Houston Chronicle

TOXIC CHEMICALS IN THE HOUSTON AREA

Multi-part series by investigative journalists from the Houston Chronicle

A memorial cross is planted in West near the spot where 15 people died, including a dozen firefighters who raced in unaware of the dangers at the West Fertilizer Company. (Michael Ciaglo / Houston Chronicle)

Original article: http://www.houstonchronicle.com/chemical-breakdown/2/

Burgess COMMENTARY

Peter Burgess

Chemical Breakdown: Part 2

Story by Mark Collette and Matt Dempsey

In an instant, his face was on fire.

Flames burned Anselmo Lopez’s arms and chest, and the explosion knocked back three co-workers whose eardrums burst.

Lopez had been doing maintenance last October, pumping inert nitrogen through pipes at the SunEdison plant outside Houston, to flush out a highly volatile gas called silane.

When his crew opened a valve, silane leaked and combined with air. The mixture ignited.

Though SunEdison over the years had paid thousands in fines from the U.S. Occupational Safety and Health Administration, safety remained a problem. Lopez’s injury — which would require multiple skin grafts and lifelong care — was the fifth time in nearly a decade that the plant had a toxic release, fire or serious safety violation.

It’s unusual that OSHA inspectors had been there at all.

Most Americans don’t know about chemical stockpiles near homes and schools, and often, the government doesn’t, either. The U.S. regulatory system is poorly funded and has outdated, complex rules that go unenforced, leaving facilities that handle hazardous chemicals mostly to police themselves, a Houston Chronicle investigation found.

The result: A government that reacts only to the worst accidents and does little to prevent them, even though the same mistakes keep happening.

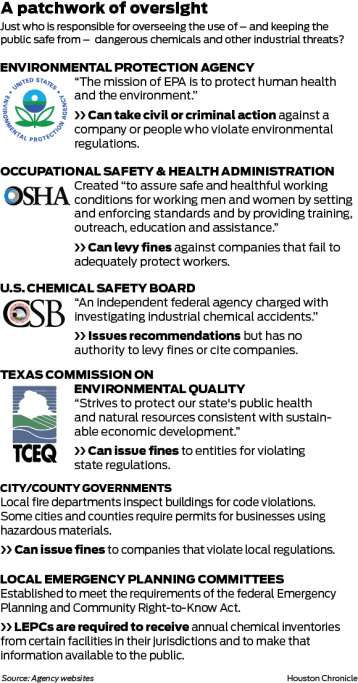

OSHA doesn’t have enough inspectors to perform its mission, and its fines are paltry, even by its own measure.

The Environmental Protection Agency left gaping holes in its regulations despite its own calls for change and the president’s mandate to make improvements.

And the U.S. Chemical Safety Board plugs along with a tiny budget, taking on massively complicated investigations and issuing recommendations that go largely ignored by federal agencies.

Not enough inspectors

Chemical safety experts from around the world gathered last year in Austin for the Global Congress on Process Safety.

Presenters and attendees talked in industry jargon — about good engineering practices and hazard studies and using data to recognize potential dangers.

Everyone was reminded about the importance of constant vigilance.

When someone wanted to lighten the mood, he’d bring up OSHA. As a punch line.

Some at the conference had little faith that OSHA inspectors are qualified to evaluate chemical process safety, and even when they are, there aren’t enough of them.

OSHA is charged with protecting American workers but has 1,840 inspectors — roughly the same since 1981 — for 8 million U.S. workplaces. Inspecting every facility one time would take 145 years, according to the AFL-CIO.

Only 267 OSHA inspectors have specialized training for about 15,000 chemical facilities.

In 2011, the agency began a chemical emphasis program, but it looks at a relatively small number of plants. An analysis by the Chronicle and researchers at the Texas A&M University Mary Kay O’Connor Process Safety Center ranked thousands of facilities in greater Houston on their potential to harm the public. OSHA did not inspect most of the top 55 facilities in the last five years.

Dr. Sam Mannan, director of the O’Connor center and one of the nation’s preeminent experts on chemical safety, advocates for third-party inspections because federal agencies aren’t doing enough. The EPA is embracing the idea in a proposed rule change, over the strong objections of industry.

Rigorous enforcement creates a dialogue between government and industry, Mannan said, and ensures that companies breaking rules don’t fall through cracks.

OSHA penalties are mostly unchanged since 1990. Fines for four deaths after a preventable gas leak in November 2014 at the DuPont plant in La Porte totaled $372,000. That's about half of 1 percent of an average day’s revenue for the corporation.

The head of OSHA, Assistant Labor Secretary David Michaels, told a Senate panel in December 2014 that “our criminal penalties are virtually meaningless.”

The imbalance between fines for environmental violations and catastrophic safety problems can reach the absurd.

In 2001, a sulfuric acid tank exploded at a refinery in Delaware, killing Jeff Davis.

“His body had virtually decomposed,” Michaels said.

Workers had long warned the company about problems with the tank. OSHA issued a $132,000 fine. Because the incident polluted air and water and killed wildlife, EPA won a $12 million civil settlement.

“Can you imagine telling Jeff Davis’ wife, Mary, their five kids that the fine for the hazards associated with his death was one-fiftieth of the fine associated with killing fish and crabs?” he said.

Not a wide enough net

The EPA is the only federal agency specifically tasked with protecting the public from chemical accidents and wields the biggest hammer in enforcement. But it traditionally has been focused on preventing and cleaning up environmental damage.

It commits less than 1 percent of its $8.6 billion budget to chemical safety. About 35 inspectors police more than 12,000 of the most dangerous facilities nationwide under its Risk Management Program.

That program, the agency’s chief prevention strategy, requires those facilities to develop emergency response procedures and to consider worst-case scenarios for toxic releases.

Only about 280 facilities in the Houston area are required to file such plans, according to federal data.

The state of chemical inspections in the U.S.

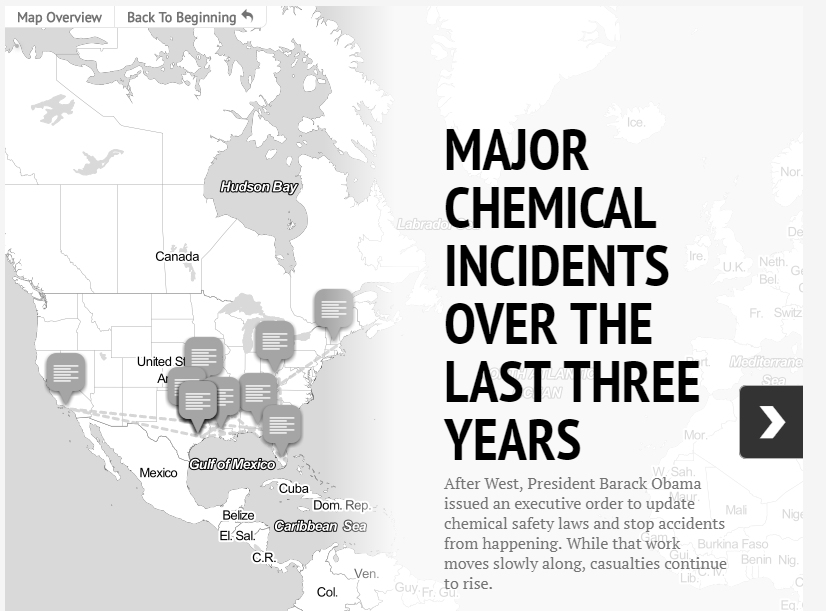

After a fertilizer plant explosion in West killed 15 people, many of them unprepared firefighters who got caught in the blaze, President Obama ordered changes. Specifically, he wanted to make sure that kind of thing never happened again, that first-responders, workers and the public at large were not surprised by deadly explosions or toxic releases. But in the three years since West, at least 82 people have been killed and 1,600 injured in over 400 incidents. The chemical industry continues to police itself. EPA and OSHA lack the staffing and funding to go after companies with suspect track records or to do much of anything in a proactive fashion.

And the EPA ignores an entire category of risk.

For years, experts have asked the EPA to regulate reactive chemical dangers, which the agency itself — along with OSHA — suggested after a New Jersey disaster in 1997.

In 2002, CSB researchers found 167 accidents over a 20-year period that involved uncontrolled chemical reactions, causing 108 deaths and hundreds of millions of dollars in property damage.

But regulations have never been updated to include reactive dangers.

There are other gaps. Fuel retailers are exempt under the RMP. Farmers using ammonia as fertilizer, such as the ammonium nitrate that killed 15 in the West Fertilizer Company explosion three years ago, also are exempt. Hundreds of dangerous chemicals aren’t covered.

The EPA has one other tool when it comes to avoiding chemical accidents — the General Duty Clause of the Clean Air Act.

The clause instructs businesses to identify hazards, design and maintain safe facilities, prevent accidental releases, and minimize consequences if a release occurs.

“It’s a powerful and broad enforcement tool for EPA,” said Jean Flores, an environmental law attorney in Dallas who represents industrial clients.

The EPA typically doesn’t use it to prevent accidents, mostly just to punish companies for chemical leaks.

Not enough follow-through

The Chemical Safety Board is to the chemical industry what the National Transportation Safety Board is to airlines, railroads and trucking firms. With fewer than 50 employees and an annual budget of just $11 million, the CSB has investigated only 16 of at least 340 chemical accidents since 2014.

Investigations are prioritized based on the number of deaths or damage. Even when it does investigate, the CSB has no authority to force change. It only makes recommendations.

In 2006, the board called on OSHA to create an industry standard for combustible dust after three separate explosions left 14 dead and more injured. After more accidents and deaths, the CSB in 2013 called the dust standard a “Most Wanted Chemical Safety Improvement.”

To date, no standard has been set.

In 2010, after a refinery explosion in Washington state, the CSB recommended requiring inherently safer technologies, like substituting equipment or chemicals for less dangerous ones. Water plants, for example, could use liquid chlorine instead of gas, which can spread into neighborhoods.

It hasn’t been done.

In Washington, that surprises no one. Since 2002, the CSB has issued 44 recommendations to federal agencies. Just 20 were adopted.

The NTSB’s recommendations over 40 years have had a clear impact on public safety. Investigations spurred improved regulations on everything from commercial truck driver training to de-icing aircraft. It helps that aviation and rail incidents require reports to the federal government, and all fatal motor vehicle crashes are reported to the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration.

There is no reporting requirement for chemical incidents.

The CSB relies primarily on media reports to track incidents nationwide, so not even the government has a clear accounting of the injuries, property and lives lost to chemical mishaps.

In all, fewer than 400 federal inspectors — through OSHA, EPA and CSB — provide oversight for the chemical industry, with a combined budget of less than $50 million a year.

The industry, by comparison, with about 15,000 manufacturing plants, has spent an average of $191 million annually on lobbying since 1998, according to the Center for Responsive Politics.

The explosion in West and its aftermath

A memorial cross is planted in West near the spot where 15 people died, including a dozen firefighters who raced in unaware of the dangers at the plant. ( Michael Ciaglo / Houston Chronicle)

A park in honor of the firefighters who died was built near the scene of the explosion. The fertilizer company is no longer in business. ( Michael Ciaglo / Houston Chronicle )

Repairs are still being made around West. ( Michael Ciaglo / Houston Chronicle )

The flooring is all that remains of a house damaged three years ago in a massive explosion at the West Fertilizer Company. ( Michael Ciaglo / Houston Chronicle )

Many homes, including this one, were damaged in the explosion. ( Michael Ciaglo / Houston Chronicle )

Crosses and flowers sit in the foundation of an apartment complex that was destroyed by the blast. ( Michael Ciaglo / Houston Chronicle )

Austin and Shay Garrett play with their 1-year-old son, Ryder, at the fireman-themed playground across from where the West Fertilizer Company exploded. The park was named after Parker Pustejovsky, whose father, Joey, a volunteer firefighter, was killed in the blast. Parker raised $220,000 to rebuild the park he used to play on with his father. ( Michael Ciaglo / Houston Chronicle )

Construction workers walk down North Reagan Street as crews continue to repair damage to the road and pipelines. ( Michael Ciaglo / Houston Chronicle )

On April 17, 2013, a mushroom cloud emerged from the explosion at the West Fertilizer plant. This picture was taken by an employee from Greg May Chevrolet in West.

Firefighters use flashlights to search a destroyed apartment complex in West.

An aerial shot of the damage. The plant is at the bottom of the photo. ( Smiley N. Pool / Houston Chronicle )

Rescue personnel and police search the debris in the aftermath. ( Smiley N. Pool / Houston Chronicle )

The plant was destroyed in the explosion.

Some of what was salvaged from an apartment complex that was destroyed in the blast.

A day after the explosion, people gather for a vigil.

Shona Jupe hugs a friend outside her former apartment building. Jupe was at her front door when the explosion happened. (AP Photo/The Dallas Morning News, Kye R. Lee)

Fire departments from around Texas pay their respects as they parade in for a memorial service on April 25, 2013. (Photo by Erich Schlegel/Getty Images)

Bishop Joe S. Vasquez speaks at the Church of the Assumption in the days after the explosion.

Jeff Clark (facing camera) comforts Dustin Matus after the mass. Matus' father, Jimmy, was killed in the explosion.

Caskets sit at the front of the stage for firefighters killed in the blast. (AP Photo/Charles Dharapak)

President Barack Obama attends the memorial for firefighters killed at the fertilizer plant. (AP Photo/Charles Dharapak)

On April 17, 2014, balloons are released in memory of those who died a year earlier in the West Fertilizer explosion. (AP Photo/Waco Tribune Herald, Jerry Larson)

Not enough action

One moment three years ago was supposed to redefine everything in chemical safety.

Firefighters rushed to a fire at West Fertilizer. Fourteen minutes later, 12 of them died in a blast that also killed three others and barely missed hundreds of students who had been in nearby classrooms hours earlier.

The perils of ammonium nitrate had not been explained to first-responders in the Central Texas community of West, nor to those who lived blocks away.

The Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives recently announced the initial fire was set intentionally by an unknown person. The CSB said the explosion could have been avoided with better regulatory oversight, plant construction, hazardous materials handling, and zoning. The town had grown perilously close to the plant over the years.

Vanessa Allen Sutherland, the board’s chairman, in January had harsh words about the state of chemical safety in America, citing “too many violent detonations and runaway reactions” and a “lack of adequate federal, state or local oversight …”

The board’s report on West reads like dozens that have come before — the major themes indistinguishable from one tragedy to the next. Government failed. Industry failed. Laws didn’t work as intended.

President Barack Obama, in West’s aftermath, issued Executive Order 13650. It called for an updated law on safety in chemical processing, mostly unchanged since 1992. It ordered federal agencies to figure out how to disclose more information to the public. And it asked them not just to improve emergency response and readiness, to thwart the kind of carnage seen at West, but also to stop accidents from happening.

Peter Boogaard, a Department of Homeland Security spokesman, said recently that the White House remains “committed to preventing similar incidents from occurring at chemical facilities and increasing overall chemical facility safety and security.”

The executive order working group — representing EPA, OSHA and others — has blown multiple deadlines and is in danger of leaving its work unfinished before the end of Obama’s presidency. OSHA has acknowledged it will take years to update process safety regulations. There is no guarantee the next administration will pick up the mantle.

Agency officials say some progress has been made: EPA is launching a national enforcement initiative in 2017-2019 aimed at chemical safety, but it would start with the same list of 12,000 facilities in its Risk Management Program. More than 400,000 locations are required to file hazardous chemical inventories.

The agency has proposed updates to the RMP. The changes would require additional hazard analysis for some companies, improved emergency preparedness and updated regulatory definitions, among other things. It won’t update or expand the list of chemicals.

The EPA says it will put renewed focus on Local Emergency Planning Committees to promote plant safety and improve emergency response.

The working group upgraded software to provide better modeling for chemical releases, took steps to simplify an array of federal databases on chemical facilities, expanded inspector training programs and, with West in mind, focused heavily on emergency planning and response.

Too heavily for Ron White, the former director of regulatory policy at the Center for Effective Government.

He’d like to see more proactive measures.

He suspects it will take the deaths of schoolchildren before the EPA will focus on prevention.

“It will take another disaster,” he said.

Read part 3: EPA’s fix is already broken

Mark Collette is a Houston Chronicle investigative reporter. E-mail: mark.collette@chron.com Twitter: @chronMC

Matt Dempsey is a Houston Chronicle data reporter. E-mail: matt.dempsey@chron.com Twitter: @mizzousundevil