Date: 2024-12-21 Page is: DBtxt003.php txt00013803

Economic Trends

New Economics Foundation / Frank Van Lerven

NORTHERN ROCK: TEN YEARS ON ... WHY DEBT IS STILL THE ISSUE

Burgess COMMENTARY

Peter Burgess

NORTHERN ROCK: TEN YEARS ON ... WHY DEBT IS STILL THE ISSUE

This week marks 10 years since the collapse of Northern Rock. As shockwaves reverberated throughout the banks, our financial system was quickly brought to its knees. One bank’s failure led to an inconceivable financial meltdown.

As the severity of the crisis sunk in, then Chancellor Gordon Brown was forced to put together an unprecedented bank bailout package. He also reportedly considered putting troops on the streets due to fears of civil unrest.

All the economic jargon and complicated financial analysis (think credit default swaps, sub-prime mortgages, asset-backed securities and derivatives) may seem abstract, but the pictures of queues of customers lining up outside Northern Rock branches are a reminder that the bank’s failure was ultimately about people.

In fact, the entire financial crisis and ensuing recession came at an incalculable human cost, the consequences of which we are still feeling today. The majority of people in Britain are still worse off now than before the crisis.

We have experienced the worst recovery from a recession since records began, and the biggest decade long decline in real wages. Of the 34 advanced economies in the OECD, only Greece has seen weaker wage growth. The typical working family is still £345 poorer than before the financial crisis, and average earnings will not reach 2007 levels until 2022.

People in the UK have been through a ‘lost decade’ of growth. While bank profits in the run-up to the crisis were privatised, their losses were clearly socialised, and people’s livelihoods are worse off for it.

DEBT IS STILL THE ISSUE

The economy tanked not because of a profligate public sector that wasn’t living within its means, but because of the massive growth in private debt (mortgage debt specifically), which somehow slipped under the radar.

Economists have shown that the connection between high private debt and financial crisis is not a recent phenomenon. Using data for 14 countries, making up 60% of world GDP, over 138 years of history (1870-2008). They found that:

“Private credit growth is a powerful predictor of financial crises, suggesting that such crises are ‘credit booms gone wrong’ and that policymakers ignore credit at their peril.”

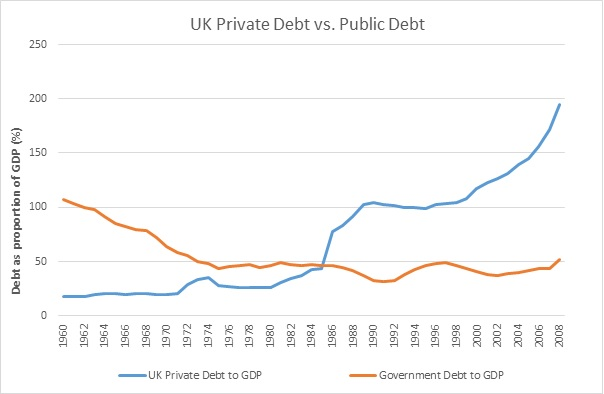

Before the 1980s, private debt in the UK had never gone beyond 75% relative to the UK economy’s income or GDP. By 2008, the level of private debt to GDP increased to 200%.

Meanwhile, throughout this entire period government debt remained steady between 35-50% of GDP. This is striking given that government debt and the ‘deficit’ is what gets all the headlines.

Source: World Bank

As long as politicians, the media, and mainstream academics keep ignoring the fundamental cause of the previous financial crisis, history somehow seems destined to repeat itself.

Of course, policy makers will say private debt is no longer a problem because the banking system is safer than it was 10 years ago. Banks are stress-testing households, they are more prudent in terms of who they lend to, and they hold more capital against loans in case things go bad.

To an extent this is true, but a Northern Rock type of bank failure is not necessary to inflict the human costs we suffered over the last decade. High levels of private debt have a massive macroeconomic impact, and can still lead to an economic meltdown.

When households and businesses in the private sector borrow rapidly, they spend more and consequently demand more goods and services. But eventually, if their income doesn’t increase at the same pace as their level of debt (i.e. if they borrow more than they can afford to), they will limit their spending in order to pay down debts that they feel are too high. As people stop spending, they reduce their demand for goods and services from businesses. With less revenue, businesses are forced to reduce employment levels or wages. Fewer jobs and lower wages force people to spend less and a vicious cycle begins – sending the economy into recession.

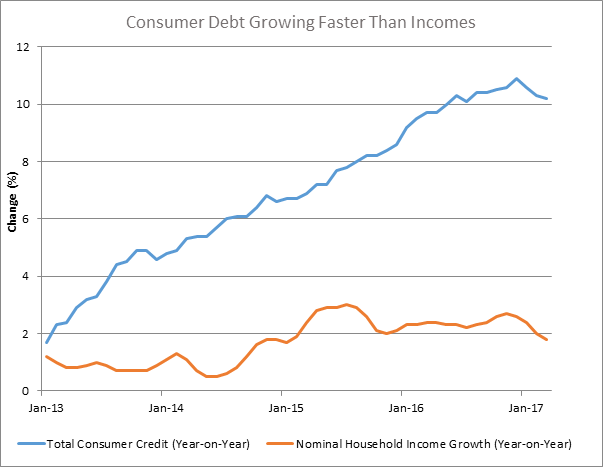

Consumer debt (including things like car finance, credit cards, and personal loans) is at a record high. As the public and business sectors have cut spending, consumer debt has been left to power our economy – growing at rates not seen since before 2008. Many predicted a recession in the aftermath of the Brexit vote, but thanks to ordinary people racking up debt on their credit cards, a recession may have been temporarily thwarted.

Propping up growth via consumer borrowing, while incomes stagnate, is hardly a sustainable growth strategy. Eventually, consumer debt will slow or come to a halt, and potentially bring our economy down with it.

Source: Bank of England and ONS

In the wake of Northern Rock, many asked what finance was ultimately for. Who does it serve? And who should it serve?

We need a financial system that serves all people, provides decent, productive and rewarding livelihoods for all and ensures the natural environment on which we all depend is protected.

Of course there is no single or straightforward answer as to how this transformation can be achieved, but we must at least begin by asking how it can better serve ordinary people.

People have the power to transform the financial system, but we must work, mobilise and learn how to exercise that power.