Date: 2024-09-27 Page is: DBtxt003.php txt00014346

The Trump Presidency

Trump / GOP Tax Reform Scam

BUSINESS ... How Trump's Corporate-Tax Plan Could Send American Jobs Overseas The president maintains his proposal would limit offshoring. A major provision of it would do just the opposite.

Burgess COMMENTARY

Peter Burgess

How Trump's Corporate-Tax Plan Could Send American Jobs Overseas

The president maintains his proposal would limit offshoring. A major provision of it would do just the opposite.

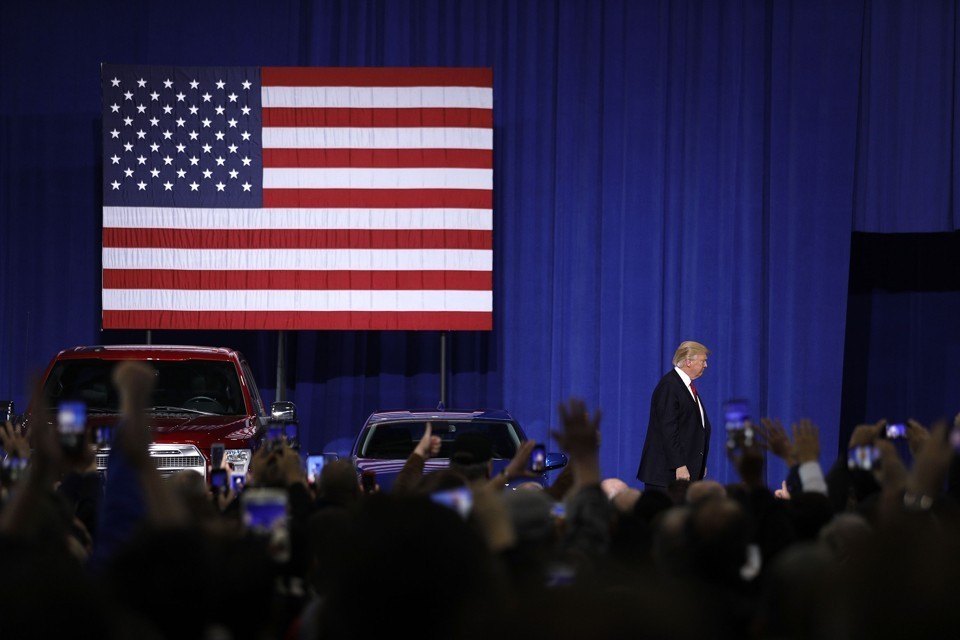

President Trump onstage in front of autoworkers in Ypsilanti, Michigan, in MarchBill Pugliano / Getty

GENE B. SPERLING NOV 1, 2017 BUSINESS

Share Tweet …

LinkedIn

Email

Print

TEXT SIZE

President Trump and his Council of Economic Advisors argue that cutting the corporate tax rate would be a major boon to American workers, in that it would substantially boost their household income. This is, as many economists and journalists have pointed out, wrong.

But there is another issue with the Trump- and GOP-proposed corporate-tax plan that has not drawn as much attention. A major provision of the plan—the full details of which are slated to be revealed on Thursday—fails its most basic claim: that it would “prevent companies from shifting profits to tax havens” and limit “offshoring.” Instead, the way that provision is designed, it would actually incentivize U.S. companies to move their operations overseas and to shift profits to tax havens.

Understanding why that’s the case requires understanding how the corporate-tax system works at the moment. Under the U.S.’s current system—a “worldwide” tax system—American corporations’ profits are taxed at the same rate regardless of whether they are earned domestically or abroad. A key difference between these two types of earnings, though, is that profits made abroad aren’t taxed in the U.S. until they are “repatriated” from a foreign subsidiary to a U.S. parent company. (In most cases, however, companies are already investing those foreign profits in American financial assets; they just can’t be returned to shareholders without triggering a corporate tax.)

The current system gets criticism from both the right and the left. Many progressives argue that by letting companies keep profits overseas indefinitely, the system incentivizes them to shift their activities and profits out of the U.S. and into countries with lower tax rates—especially tax havens. Meanwhile, many conservatives and pro-business interests argue that forcing U.S. multinationals to pay taxes on profits they make overseas (after subtracting the taxes they paid to the foreign country) makes them less competitive in foreign markets. There’s also a conservative argument that the system leads companies to stash money in overseas subsidiaries that they might otherwise bring back and invest in the United States if they didn’t get taxed on their foreign income upon repatriation.

Aware of those criticisms, President Obama suggested reforms in 2012 that sought to find some common ground. First, his plan would have imposed a one-time tax on foreign profits that have never been taxed, with all of the proceeds going toward financing a major infrastructure package. (Trump’s proposal has no such infrastructure provision.) Second, Obama sought to lower corporate rates while at the same time eliminating enough loopholes so that the overall amount of taxes that corporations pay wouldn’t change and the deficit wouldn’t increase. (Under Trump’s plan, the net tax cut to corporations is about $2 trillion over 10 years, according to an estimate from the nonpartisan Tax Policy Center.)

And third, Obama proposed a per-country minimum tax on foreign profits, meaning that there’d be a baseline rate—19 percent was what he put forward—that all companies would be required to pay on foreign profits, even if their operations and earnings were coming from countries with extremely low rates. Thus, if a U.S. company booked profits in a tax haven with a corporate rate of only 5 percent, that company would be taxed that year at a rate of 14 percent by the the U.S. government, for a total rate of 19 percent. The idea was that a per-country minimum tax would make it useless for a company to spend time and money shifting profits to tax havens.

The Trump-GOP plan will also propose a minimum tax rate on foreign income, according to multiple reports. But whereas Obama’s plan (which ultimately didn’t become law) assessed a company’s taxation in each country individually, the Trump framework would come up with an average for all foreign earnings combined, a so-called “global minimum.”

This might seem like a small difference, but the design of their global minimum tax creates perverse incentives for companies to offshore jobs and shift profits to tax havens—outcomes that a per-country minimum tax would avoid. How? Consider two examples, assuming for simplicity that the GOP plan would impose a domestic corporate tax rate of 20 percent (as the Treasury has said it will) and a rate of 10 percent on overseas earnings (it’s expected to be in the range of 10 to 15 percent, but that won’t be known for certain until Thursday). Say there’s a company with two branches that each produce $100 million in profits a year, one in Minneapolis that faces the domestic rate of 20 percent and one in Bermuda, a country that has a corporate tax rate of zero. If the GOP plan used Obama’s per-country-minimum approach, the company would pay $20 million in taxes on its profits in Minneapolis and $10 million on its profits in Bermuda. In total, the company would pay $30 million on $200 million of profits.

This situation changes dramatically if that per-country assessment is replaced by the global minimum in the Trump-GOP plan. All the company has to do to cut its tax bill is move its Minneapolis operation to a country with a corporate tax rate in the neighborhood of what the GOP is proposing, such as the U.K., France, and Germany. That’s because if the company pays $20 million to the U.K. government—instead of to the U.S. government—and still faces no taxes in Bermuda, then it would achieve a 10 percent average on its foreign profits, meaning it would avoid triggering the minimum tax altogether and cut its total tax bill from $30 million to $20 million. On top of this, all of the company’s tax revenues that used to go to the U.S. government now go to the U.K.

This is a big flaw in Trump’s plan: The more an American company moves its profitable operations to countries that have tax rates of 20 percent or higher—often rich countries that are seen as America’s economic competitors—the more that company can shift profits to tax havens without paying taxes on those profits. And the more that U.S. companies already take advantage of tax havens, the bigger the incentive they will have to offshore operations to other advanced countries: This provision of the GOP plan encourages companies to blend income from low-tax countries with that from higher-tax countries, completely avoiding paying money to the U.S. government.

Many economists agree about the problems with this global minimum tax. As Kimberly Clausing, a professor of economics at Reed College who specializes in international taxation, told the Senate Finance Committee in early October, companies would be able to “use taxes paid in Germany to offset the Bermuda income and then you have an incentive to move income to both Bermuda and Germany.” Similarly, Ed Kleinbard, a law professor at USC and a former chief of staff of Congress’s Joint Committee on Taxation, told Bloomberg, “Companies will double down on tax-planning technologies to create a stream of zero-tax income that brings their average down to that minimum rate.”

Why would Trump and Republicans in Congress support a plan designed to incentivize sending jobs overseas and transferring tax revenues from the U.S. to other countries? The answer is that such a plan would please large multinational companies, who lobbied heavily for a minimum tax on foreign earnings to be watered down. In other words, instead of a minimum tax that would discourage companies from moving jobs and shifting profits overseas, Trump and congressional Republicans have settled on one that would encourage more of both.

===================================================================================================

QUICK LINKS

James Fallows

Ta Nehisi Coates

How the Tax Plan Will Send Jobs Overseas

Companies are going to be able to save a ton of money by locating factories abroad.

John Minchillo / AP

Despite Donald Trump’s “America first” rhetoric, many suspected that the tax plan he would support would actually increase the incentives for U.S. multinationals to move both profits and operations overseas. I wrote about this inevitability a few weeks ago, [see above] before the details of the Trump-GOP tax plan emerged.

Now that the bill is advancing, it’s clear that things aren’t as bad as many feared. They’re worse.

As discussed in the previous piece, Trump administration economic officials argue that by lowering the corporate tax rate from 35 percent to 20 percent and moving to what is called a territorial system—mainly, companies pay taxes on foreign earnings only to the foreign nation where those profits are booked and never owe anything to the U.S. no matter how low the foreign nation’s tax rate is—would lead to more jobs and profits staying in or coming back to the United States.

Yet, it is clear that a territorial system could have just the opposite impact: It could give a permanent preference to foreign income and lead companies to shift more profits to tax havens knowing that they could permanently avoid virtually all taxation on such profits. One crucial safeguard against that perverse impact is to apply a strong minimum tax on the profits of U.S. multinationals in each country (a “country-by-country” minimum tax). If a U.S. company had to pay a minimum tax of, let’s say, 19 percent (as President Obama had proposed), even if they engaged in complex tax planning to book $100 million in profits in zero-tax Bermuda, they would have to pay $19 million in U.S. taxes to ensure the 19 percent minimum tax was enforced. Under such a country-by-country minimum tax, you can run, you can shift profits to tax havens, but you cannot hide from paying a 19 percent minimum no matter where you are. Under this type of true minimum tax on foreign earnings, U.S. multinationals would have little incentive to engage in the ongoing race to the bottom.

As discussed in my previous Atlantic piece, the GOP plan was rumored to use only a 10 percent minimum tax, and to make it worse, would make the minimum tax determination based on the average of a company’s total global profits. What was problematic about this design was that it not only encouraged companies to move profits to tax havens, but it actually encouraged them to simultaneously move jobs and operations such as manufacturing to industrialized countries that had typical tax rates and to shift more profits to tax havens. Why? Because if you had $100 million of profits in Bermuda facing no tax, you might have still had to pay $10 million in U.S. taxes to meet the new global minimum tax. But if you moved a factory to Germany that made $100 million and paid 20 percent in taxes there, you could still pay zero on your profits in Bermuda because the average taxes paid on your global profits (from both Bermuda and Germany) would be the global minimum rate of 10 percent. This perverse design means the more a U.S. multinational shifts jobs and operations to industrialized nations with similar tax rates to the U.S., the more it can get away with shifting more and more profits to tax havens.

So how did it look in the fine print? As several tax experts including the Tax Policy Center’s Steve Rosenthal, Brooklyn Law School’s Rebecca Kysar, and Reed College’s Kimberly Clausing have written, it is even worse than anticipated on at least two additional grounds. First, it turns out that the Republican idea of a minimum tax is that it only taxes what you make over what they think is a “routine” profit, deemed to be 10 percent in the Senate bill, on “tangible” investments (think factories and equipment, including for manufacturing). As Rosenthal notes, “because ‘routine’ returns are not subject to U.S. tax, this definition of ‘routine’ returns could give U.S. firms a perverse incentive to shift more tangible assets to lower-taxed overseas locations.” That means, under the GOP bills, if you shift less profitable operations to a tax haven you would pay zero taxes on those operations as long as you are only making 10 percent a year—whether that is $10 million or $100 million—while you would pay 20 percent if the operations were located in the United States. So, the “minimum” tax is really a much lower rate than 10 percent, and would essentially be an invisible, non-existent tax except on highly profitable operations and income from intangibles.

Second, this limitation to only excess profits encourages even more shifting of operations and jobs overseas through complex efforts to blend different income streams. How? Profits from “intangibles” like patents do not receive the 10 percent exemption for “routine” returns, so the minimum tax is seemingly designed to at least capture those well-known cases where major technology companies shift intangibles to low-tax nations and book their profits there. If a company does that and earns extraordinary profits, a global minimum tax would capture some piece of that. But again, here is where the GOP bill’s global “averaging” actually creates the incentives to move jobs and operations overseas.

Let’s say a U.S. multinational has highly profitable intangibles located in a tax haven that earn $50 million in income without any tangible investment. If the company has no other foreign profits or operations, then that income would face a mere $5 million in U.S. taxes from the 10 percent minimum tax under the GOP plan. But if the company decides to build a new $1 billion factory overseas that earns profits of only 5 percent ($50 million) from the factory, the company will not pay a penny in U.S. taxes on its income from the factory or the intangibles. Why? Because when you add the income together, the $50 million from the intangibles plus the $50 million from the new factory, it equals the “routine” profit of 10 percent on the $1 billion of new tangible investment, which will allow it to completely avoid paying taxes on any of the above mentioned profits.

This shows how deeply the tax plan fails when it comes to incentives to shift profits and operations overseas and to curtail the obsession of major multinational companies with international tax arbitrage that has nothing to do with innovation, productivity or job creation. Indeed, the ability to blend income from intangibles and routine profits, and from investment in higher tax nations with tax havens with zero taxes, leads to a worst of all worlds scenario: an even greater corporate focus on international tax minimization through a careful mixture of shifting profits and operations overseas.

If there was one thing the GOP international tax bill was advertised to accomplish, it was that it would favor locating jobs and profits in the United States. It does just the opposite—expanding the degree our tax system tilts the playing field against American taxpayers and American workers.

Related Video

==============================================================================================

Share Tweet Comments

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

GENE B. SPERLING is a contributing editor at The Atlantic. He was the national economic adviser to U.S. President Bill Clinton from 1996 to 2001 and to U.S. President Barack Obama from 2011 to 2014.

Twitter