Date: 2024-10-31 Page is: DBtxt003.php txt00014498

Jobs / Unemployment

Pew Research

Pew Research REPORT ... The Future of Jobs and Jobs Training

Burgess COMMENTARY

Peter Burgess

Pew-Research-Center-Future-of-Work-Jobs-Training-and-Skills.pdf

The Future of Jobs and Jobs Training

As robots, automation and artificial intelligence perform more tasks and there is massive disruption of jobs, experts say a wider array of education and skills-building programs will be created to meet new demands. There are two uncertainties: Will well-prepared workers be able to keep up in the race with AI tools? And will market capitalism survive?

(Bill O'Leary/The Washington Post)

Machines are eating humans’ jobs talents. And it’s not just about jobs that are repetitive and low-skill. Automation, robotics, algorithms and artificial intelligence (AI) in recent times have shown they can do equal or sometimes even better work than humans who are dermatologists, insurance claims adjusters, lawyers, seismic testers in oil fields, sports journalists and financial reporters, crew members on guided-missile destroyers, hiring managers, psychological testers, retail salespeople, and border patrol agents. Moreover, there is growing anxiety that technology developments on the near horizon will crush the jobs of the millions who drive cars and trucks, analyze medical tests and data, perform middle management chores, dispense medicine, trade stocks and evaluate markets, fight on battlefields, perform government functions, and even replace those who program software – that is, the creators of algorithms.

People will create the jobs of the future, not simply train for them, and technology is already central. It will undoubtedly play a greater role in the years ahead.

JONATHAN GRUDIN

Multiple studies have documented that massive numbers of jobs are at risk as programmed devices – many of them smart, autonomous systems – continue their march into workplaces. A recent study by labor economists found that “one more robot per thousand workers reduces the employment to population ratio by about 0.18-0.34 percentage points and wages by 0.25-0.5 percent.” When Pew Research Center and Elon University’s Imagining the Internet Center asked experts in 2014 whether AI and robotics would create more jobs than they would destroy, the verdict was evenly split: 48% of the respondents envisioned a future where more jobs are lost than created, while 52% said more jobs would be created than lost. Since that expert canvassing, the future of jobs has been at the top of the agenda at many major conferences globally.

Several policy and market-based solutions have been promoted to address the loss of employment and wages forecast by technologists and economists. A key idea emerging from many conversations, including one of the lynchpin discussions at the World Economic Forum in 2016, is that changes in educational and learning environments are necessary to help people stay employable in the labor force of the future. Among the six overall findings in a new 184-page report from the National Academies of Sciences, the experts recommended: “The education system will need to adapt to prepare individuals for the changing labor market. At the same time, recent IT advances offer new and potentially more widely accessible ways to access education.”

Jobholders themselves have internalized this insight: A 2016 Pew Research Center survey, “The State of American Jobs,” found that 87% of workers believe it will be essential for them to get training and develop new job skills throughout their work life in order to keep up with changes in the workplace. This survey noted that employment is much higher among jobs that require an average or above-average level of preparation (including education, experience and job training); average or above-average interpersonal, management and communication skills; and higher levels of analytical skills, such as critical thinking and computer skills.

A central question about the future, then, is whether formal and informal learning structures will evolve to meet the changing needs of people who wish to fulfill the workplace expectations of the future. Pew Research Center and Elon’s Imagining the Internet Center conducted a large-scale canvassing of technologists, scholars, practitioners, strategic thinkers and education leaders in the summer of 2016, asking them to weigh in on the likely future of workplace training.

Some 1,408 responded to the following question, sharing their expectations about what is likely to evolve by 2026:

In the next 10 years, do you think we will see the emergence of new educational and training programs that can successfully train large numbers of workers in the skills they will need to perform the jobs of the future?

The nonscientific canvassing found that 70% of these particular respondents said “yes” – such programs would emerge and be successful. A majority among the 30% who said “no” generally do not believe adaptation in teaching environments will be sufficient to teach new skills at the scale that is necessary to help workers keep abreast of the tech changes that will upend millions of jobs. (See “About this canvassing of experts” for further details about the limits of this sample.)

Participants were asked to explain their answers and offered the following prompts to consider:

... What are the most important skills needed to succeed in the workforce of the future?

... Which of these skills can be taught effectively via online systems – especially those that are self-directed – and other nontraditional settings?

... Which skills will be most difficult to teach at scale?

... Will employers be accepting of applicants who rely on new types of credentialing systems, or will they be viewed as less qualified than those who have attended traditional four-year and graduate programs?

Several common expectations were evident in these respondents’ answers, no matter how hopeful or fretful they were about the future of skills- and capabilities-training efforts. (It is important to note that many respondents listed human behaviors, attributes and competencies in describing desirable work skills. Although these aspects of psychology cannot be classified as “skills” and perhaps cannot be directly taught in any sort of training environment, we include these answers under the general heading of skills, capabilities and attributes.)

A diversifying education and credentialing ecosystem: Most of these experts expect the education marketplace – especially online learning platforms – to continue to change in an effort to accommodate the widespread needs. Some predict employers will step up their own efforts to train and retrain workers. Many foresee a significant number of self-teaching efforts by jobholders themselves as they take advantage of proliferating online opportunities.

Respondents see a new education and training ecosystem emerging in which some job preparation functions are performed by formal educational institutions in fairly traditional classroom settings, some elements are offered online, some are created by for-profit firms, some are free, some exploit augmented and virtual reality elements and gaming sensibilities, and a lot of real-time learning takes place in formats that job seekers pursue on their own.

A considerable number of respondents to this canvassing focused on the likelihood that the best education programs will teach people how to be lifelong learners. Accordingly, some say alternative credentialing mechanisms will arise to assess and vouch for the skills people acquire along the way.

A focus on nurturing unique human skills that artificial intelligence (AI) and machines seem unable to replicate: Many of these experts discussed in their responses the human talents they believe machines and automation may not be able to duplicate, noting that these should be the skills developed and nurtured by education and training programs to prepare people to work successfully alongside AI. These respondents suggest that workers of the future will learn to deeply cultivate and exploit creativity, collaborative activity, abstract and systems thinking, complex communication, and the ability to thrive in diverse environments.

One such comment came from Simon Gottschalk, a professor in the department of sociology at the University of Nevada, Las Vegas: “The skills necessary at the higher echelons will include especially the ability to efficiently network, manage public relations, display intercultural sensitivity, marketing, and generally what author Dan Goleman would call ‘social’ and ‘emotional’ intelligence. [This also includes] creativity, and just enough critical thinking to move outside the box.”

Another example is the response of Fredric Litto, a professor emeritus of communications and longtime distance-learning expert from the University of São Paulo: “We are now in the transitional stage of employers gradually reducing their prejudice in the hiring of those who studied at a distance, and moving in favor of such ‘graduates’ who, in the workplace, demonstrate greater proactiveness, initiative, discipline, collaborativeness – because they studied online.”

Other respondents mentioned traits including leadership, design thinking, “human meta communication,” deliberation, conflict resolution, and the capacity to motivate, mobilize and innovate. Still others spoke of more practical needs that could help workers in the medium term – to work with data and algorithms, to implement 3-D modeling and work with 3-D printers, or to implement the newly emerging capabilities in artificial intelligence and augmented and virtual reality. Jonathan Grudin, principal researcher at Microsoft, commented, “People will create the jobs of the future, not simply train for them, and technology is already central. It will undoubtedly play a greater role in the years ahead.”

Seriously? You’re asking about the workforce of the future? As if there’s going to be one?

ANONYMOUS SCIENTIFIC EDITOR

About a third of respondents expressed no confidence in training and education evolving quickly enough to match demands by 2026. Some of the bleakest answers came from some of the most respected technology analysts. For instance, Jason Hong, an associate professor at Carnegie Mellon University, wrote, “There are two major components needed for a new kind of training program at this scale: political will and a proven technology platform. Even assuming that the political will (and budget) existed, there’s no platform today that can successfully train large numbers of people. MOOCs [Massive Open Online Courses] have a high dropout rate and have serious questions about quality of instruction. They are also struggling with basic issues like identification of individuals taking the courses. So in short, we can train small numbers of individuals (tens of thousands) per year using today’s community colleges and university systems, but probably not more.”

Several respondents argued that job training is not a primary concern at a time when accelerating change in market economies is creating massive economic divides that seem likely to leave many people behind. An anonymous scientific editor commented, “Seriously? You’re asking about the workforce of the future? As if there’s going to be one? … ‘Employers’ either run sweatshops abroad or hire people in the ‘first world’ to do jobs that they hate, while more and more unskilled and skilled people end up permanently on welfare or zero-hour contracts. And the relatively ‘job-secure’ qualified people who work in the ‘professions’ are probably a lot closer than they think they are to going over that same cliff. The details of how they earn their credentials aren’t going to be an issue.”

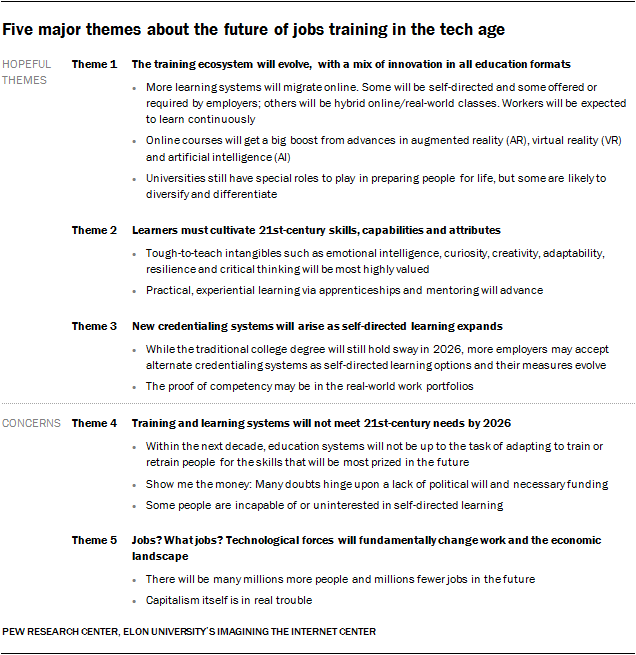

Most participants in this canvassing wrote detailed elaborations explaining their positions, though they were allowed to respond anonymously. Their well-considered comments provide insights about hopeful and concerning trends. These findings do not represent all possible points of view, but they do reveal a wide range of striking observations. Respondents collectively articulated five major themes that are introduced and briefly explained in the 29-page section below and then expanded upon in more-detailed sections. Some responses are lightly edited for style or due to length.

The following section presents a brief overview of the most evident themes extracted from the written responses, including a small selection of representative quotes supporting each point. Some responses are lightly edited for style or due to length.

------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Theme 1: The training ecosystem will evolve, with a mix of innovation in all education formats

These experts envision that the next decade will bring a more widely diversified world of education and training options in which various entities design and deliver different services to those who seek to learn. They expect that some innovation will be aimed at emphasizing the development of human talents that machines cannot match and at helping humans partner with technology. They say some parts of the ecosystem will concentrate on delivering real-time learning to workers, often in formats that are self-taught.

Commonly occurring ideas among the responses in this category are collected below under headings reflecting subthemes.

More learning systems will migrate online. Some will be self-directed and some offered or required by employers; others will be hybrid online/real-world classes. Workers will be expected to learn continuously

Most experts seem to have faith that rapid technological development and a rising wariness of coming impacts of the AI/robotics revolution are going to spur the public, private and governmental actions needed for education and training systems to be adapted to deliver more flexible, open, adaptable, resilient, certifiable and useful lifelong learning.

Educators have always found new ways of training the next generation of students for the jobs of the future, and this generation will be no different.

JUSTIN REICH

Jim Hendler, a professor of computer science at Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute, predicted, “The nature of education will change to a mix of models. College education (which will still favor multi-year, residential education) will need to be more focused on teaching students to be lifelong learners, followed by more online content, in situ training, and other such [elements] to increase skills in a rapidly changing information world. As automation puts increasing numbers of low- and middle-skill workers out of work, these models will also provide for certifications and training needs to function in an increasingly automated service sector.”

Michael Wollowski, an associate professor of computer science at the Rose-Hulman Institute of Technology, commented, “We will definitely see a vast increase in educational and training programs. We will also see what might be called on-demand or on-the-job kind of training programs. (We kind of have to, as with continued automation, we will need to retrain a large portion of the workforce.) I strongly believe employers will subscribe to this idea wholeheartedly; it increases the overall education of their workforce, which benefits their bottom line. Nevertheless, I am a big believer in the college experience, which I see as a way to learn what you are all about, as a person and in your field of study. The confidence in your own self and your abilities cannot be learned in a short course. It takes life experience, or four years at a tough college. At a good college, you are challenged to be your best – this is very resource-intensive and cannot be scaled at this time.”

Justin Reich, executive director at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) Teaching Systems Lab, observed, “Educators have always found new ways of training the next generation of students for the jobs of the future, and this generation will be no different. Our established systems of job training, primarily community colleges and state universities, will continue to play a crucial role, though catastrophically declining public support for these institutions will raise serious challenges.”

David Karger, a professor of computer science at MIT, wrote, “Most of what we now call online learning is little more than glorified textbooks, but the future is very promising. … No matter how good our online teaching systems become, the current four-year college model will remain dominant for quite some time. … Online teaching will increase the reach of the top universities, which will put pressure on lesser universities to demonstrate value. One potential future would be for those universities to abandon the idea that they have faculty teaching their own courses and instead consist entirely of a cadre of (less well paid) teaching assistants who provide support for the students who are taking courses online.”

A few respondents said already established institutions cannot be as fully successful as new initiatives. Jerry Michalski, founder at REX, commented, “Today’s educational and training institutions are a shambles. They take too long to teach impractical skills and knowledge not connected to the real world, and when they try to tackle critical thinking for a longer time scale, they mostly fail. The sprouts of the next generation of learning tools are already visible. Within the decade, the new shoots will overtake the wilting vines, and we will see all sorts of new initiatives, mostly outside these schooling, academic and training institutions, which are mostly beyond repair. People will shift to them because they work, because they are far less expensive and because they are always available.”

Barry Chudakov, founder and principal at Sertain Research and StreamFuzion Corp., says education has been liberated because, thanks to digital innovation, everyone can embed learning continuously in their everyday lives. He wrote, “The key to education in the next 10 years will be the understanding that we now live in a world without walls – and so the walls of the school (physical and conceptual) need to shatter and never go up again. In the (hopefully near) future, we will not segregate schooling from work and real-world thinking and development. They will seamlessly weave into a braid of learning, realization, exposure, hands-on experience and integration into students’ own lives. And, again, the experience of being a student, now confined to grade school, secondary school and university, will expand to include workers, those looking for work, and those who want or need to retrain – as well as what we now think of as conventional education. One way we will break down these walls – we are already doing so – will be to create digital learning spaces to rival classrooms as ‘places’ where learning happen[s]. Via simulation, gaming, digital presentations – combined with hands-on, real-world experience – learning and re-education will move out of books and into the world. The more likely enhancement will be to take digital enhancements out into the world – again, breaking down the walls of the classroom and school – to inform and enhance experience.”

An anonymous respondent echoed the sentiment of quite a few others who do not think it is possible to advance and enhance online education and training much in the next decade, writing, “These programs have a cost, and too few are willing to sacrifice for these programs.” More such arguments are included in later sections of this report.

Online courses will get a big boost from advances in augmented reality (AR), virtual reality (VR) and artificial intelligence (AI)

Some respondents expressed confidence in the best of current online education and training options, saying online course options are cost-effective, evolving for the better, and game-changing because they are globally accessible. Those with the most optimism expect great progress will be made in augmented reality (AR), virtual reality (VR) and AI. While some say 2026 will still be “early days” for this tech, many are excited about its prospects for enhancing learning in the next decade.

Already, today there are quite effective online training and education systems, but they are not being implemented to their full potential.

EDWARD FRIEDMAN

Edward Friedman, professor emeritus of technology management at the Stevens Institute of Technology, wrote, “Already, today there are quite effective online training and education systems, but they are not being implemented to their full potential. These applications will become more widely used with familiarity that is gained during the next decade. Also, populations will be more tech-savvy and be able to make use of these systems with greater personal ease. In addition, the development of virtual reality, AI assistants and other technological advances will add to the effectiveness of these systems. There will be a greater need for such systems as the needs for new expertise in the workforce [increase] and the capacity of traditional education systems proves that it is not capable of meeting the need in a cost-effective manner.”

The president of a technology LLC wrote, “Training, teaching are all going online, partly because of high costs of campus education.”

Richard Adler, distinguished fellow at the Institute for the Future, predicted, “AI, voice-response, telepresence VR and gamification techniques will come together to create powerful new learning environments capable of personalizing and accelerating learning across a broad range of fields.”

Ray Schroeder, associate vice chancellor for online learning at the University of Illinois, Springfield, commented, “It is projected that those entering the workforce today will pursue four or five different careers (not just jobs) over their lifetime. These career changes will require retooling, training and education. The adult learners will not be able to visit physical campuses to access this learning; they will learn online. I expect that we will see the further development of artificially intelligent teaching specialists such as ‘Jill Watson’ at Georgia Tech, the virtual graduate assistant who was thought to be human by an entire class of computer science students. I anticipate the further development and distribution of holoportation technologies such as those developed by Microsoft using HoloLens for real-time, three-dimensional augmented reality. These teaching tools will enable highly sophisticated interactions and engagement with students at a distance. They will further fuel the scaling of learning to reach even more massive online classes.”

Fredric Litto, an professor emeritus of communications and longtime distance-learning expert from the University of São Paulo, replied, “There is no field of work that cannot be learned, totally or in great part, in well-organized and administered online programs, either in traditional ‘course’ formats, or in self-directed, independent learning opportunities, supplemented, when appropriate, by face-to-face, hands-on, practice situations.”

Tawny Schlieski, research director at Intel and president of the Oregon Story Board, explained, “New technologies of human/computer interaction like augmented and virtual reality offer the possibility of entirely new mechanisms of education. … Augmented and virtual reality tools … make learning more experiential, they engage students with physical movement, and they enable interactive and responsive instructional assets. As these tools evolve over the next decade, the academics we work with expect to see radical change in training and workforce development, which will roll into (although probably against a longer timeline) more traditional institutions of higher learning.”

Universities still have special roles to play in preparing people for life, but some are likely to diversify and differentiate

Many respondents said real-world, campus-based higher education will continue to thrive during the next decade. They generally expect that no other educational experience can match residential universities’ capabilities for fully immersive, person-to-person learning, as well as mentoring and socializing functions, before 2026. They said a residential university education helps build intangible skills that are not replicable online and thus deepens the skills base of those who can afford to pay for such an education, but they expect that job-specific training will be managed by employers on the job and via novel approaches. Some say major universities’ core online course content, developed with all of the new-tech bells and whistles, will be marketed globally and adopted as baseline learning in smaller higher education locales, where online elements from major MOOCs can be optimally paired in hybrid learning with in-person mentoring activities.

The most important skills to have in life are gained through interpersonal experiences and the liberal arts. … Human bodies in close proximity to other human bodies stimulate real compassion, empathy, vulnerability and social-emotional intelligence.

FRANK ELAVSKY

Uta Russmann, communications/marketing/sales professor at the FHWien University of Applied Sciences in Vienna, Austria, said, “In the future, more and more jobs will require highly sophisticated people whose skills cannot be trained in ‘mass’ online programs. Traditional four-year and graduate programs will better prepare people for jobs in the future, as such an education gives people a general understanding and knowledge about their field, and here people learn how to approach new things, ask questions and find answers, deal with new situations, etc. – all this is needed to adjust to ongoing changes in work life. Special skills for a particular job will be learned on the job.”

Frank Elavsky, data and policy analyst at Acumen LLC, responded, “The most important skills to have in life are gained through interpersonal experiences and the liberal arts. … Human bodies in close proximity to other human bodies stimulate real compassion, empathy, vulnerability and social-emotional intelligence. These skills are imperative to focus on, as the future is in danger of losing these skillsets from the workforce. Many people have gained these skills throughout history without any kind of formal schooling, but with the growing emphasis on virtual and digital mediums of production, education and commerce, people will have less and less exposure to other humans in person and other human perspectives.”

Isto Huvila, professor at Uppsala University, replied, “The difference between educating to perform and educating to make the future is the difference between vocational [education] and higher (university) education. … Spending four years at a university is not only about learning skills but about bildung (self-cultivation) and socialising in a group that is capable of fostering collaboration much better than an ad hoc group of people. But this does not mean that alternative means and paths of learning and accreditation would not be useful as … complementary to the traditional system that has limitations as well.”

Dana Klisanin, psychologist/futurist at Evolutionary Guidance Media R&D, wrote, “Educational institutions that succeed will use the tools of social media and game design to grant students’ access to teachers from all over the world and increase their motivation to succeed. … Online educational programs will influence the credentialing systems of traditional institutions, and online institutions will increasingly offer meet-ups and mingles such that a true hybrid educational approach emerges.”

------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Theme 2: Learners must cultivate 21st‑century skills, capabilities and attributes

Will training for skills most important in the jobs of the future work well in large-scale settings by 2026? Respondents in this canvassing overwhelmingly said yes, anticipating that improvements in such education would continue. However, many believe the most vital skills are not easy to teach, learn or evaluate in any education or training setting available today.

Tough-to-teach intangible skills, capabilities and attributes such as emotional intelligence, curiosity, creativity, adaptability, resilience and critical thinking will be most highly valued

Dozens of descriptive terms were applied by respondents as they noted the skills, capabilities and attributes they see as important in workers’ lives in the next decade.

The skills needed to succeed in today’s world and the future are curiosity, creativity, taking initiative, multi-disciplinary thinking and empathy. These skills, interestingly, are the skills specific to human beings that machines and robots cannot do …

TIFFANY SHLAIN

While coding and other “hard skills” were listed as being easiest to teach to a large group in an online setting, “soft,” “human” skills were seen by most respondents as crucial for survival in the age of AI and robotics.

Devin Fidler, research director at the Institute for the Future, predicted, “As basic automation and machine learning move toward becoming commodities, uniquely human skills will become more valuable. There will be an increasing economic incentive to develop mass training that better unlocks this value.”

Susan Price, a digital architect at Continuum Analytics, commented, “Increasingly, machines will perform tasks they are better suited to perform than humans, such as computation, data analysis and logic. Functions requiring emotional intelligence, empathy, compassion, and creative judgment and discernment will expand and be increasingly valued in our culture.”

Tiffany Shlain, filmmaker and founder of the Webby Awards, wrote, “The skills needed to succeed in today’s world and the future are curiosity, creativity, taking initiative, multi-disciplinary thinking and empathy. These skills, interestingly, are the skills specific to human beings that machines and robots cannot do, and you can be taught to strengthen these skills through education. I look forward to seeing innovative live and online programs that can teach these at scale.”

Ben Shneiderman, professor of computer science at the University of Maryland, observed, “Students can be trained to be more innovative, creative and active initiators of novel ideas. Skills of writing, speaking and making videos are important, but fundamental skills of critical thinking, community building, teamwork, deliberation/dialogue and conflict resolution will be powerful. A mindset of persistence and the necessary passion to succeed are also critical.”

Louisa Heinrich, founder at Superhuman Limited, commented, “Lateral and system-thinking skills are increasingly critical for success in an ever-changing global landscape, and these will need to be re-prioritised at all levels of education.”

An anonymous technologist commented, “Programming and problem solving, learning how to work with artificial intelligence and robotics will become more important, and more and more workers will be replaced by software/hardware-based ‘workers.’ Automation will reduce the need for the current workforce, and the divide between the upper class and the lower class will continue to eat the middle class.”

Some who are pessimistic about the future of human work due to advances in capable AI and robotics mocked the current push in the U.S. to train more people in technical skills. An anonymous respondent commented, “Teach a billion people to program and you’ll end up with 900,000,000 unemployed programmers.”

An anonymous program director for a major U.S. technology funding organization predicted, “We will see training for the jobs of the past, and for service jobs. The jobs of the future will not need large numbers of workers with a fixed set of skills – most things that we can train large numbers of workers for, we will also be able to train computers to do better.”

Among the many other skills mentioned were: process-oriented and system-oriented thinking; journalistic skills, including research, evaluation of multiple sources, writing and speaking; understanding algorithms, computational thinking, networking and programming; grasping law and policy; an evidence-based way of looking at the world; time management; conflict resolution; decision-making; locating information in the flood of data; storytelling using data; and influencing and consensus building. A few people mentioned that young adults need to be taught how to have face-to-face interaction, including one who said they “seem to be sorely lacking in these skills and can only interact with a cellphone or laptop.”

Practical experiential learning via apprenticeships and mentoring will advance

Because so many intricacies of the workplace – the human, soft and hard – are learned on the job, respondents said they expect apprenticeships and forms of mentoring will regain value and evolve along with the 21st‑century workplace.

D. Yvette Wohn, assistant professor of information systems at the New Jersey Institute of Technology, wrote, “Formalized apprenticeships that require both technical skills and interpersonal interaction will become more important.”

Ian O’Byrne, an assistant professor of literacy education at the College of Charleston, replied, “In the future we’ll see more opportunities for online, personalized learning. This will include open, online learning experiences (e.g., MOOCs) where individuals can lurk and build up capacity or quench interests. I also believe that we’ll see a rise in the offering of premium or pay content that creates a space where one-to-one learning and interaction will allow mentors to guide learners while providing critical feedback. We will identify opportunities to build a digital version of the apprenticeship learning models that have existed in the past. Alternative credentials and digital badges will provide more granular opportunities to document and archive learning over time from traditional and nontraditional learning sources. Through evolving technologies (e.g., blockchain), this may provide opportunities for learners to document and frame their own learning pathways.”

An instructional designer with 19 years of experience commented, “The pattern I’m seeing is toward individualized learning – almost on the level of tutoring or apprenticeship. We’ve seen again and again that the broader the audience focus, the less the course seems to deliver. As for what the skills of the future are, they’ll be specialized to their fields with a university degree assumed to be a certificate in the ability to learn more about a particular subject specialty. You may get a degree in computer software development, but the truth is that you still need to be taught how to write software for, say, the mortgage company or insurance company that hires you. The key to the future will be flexibility and personal motivation to learn and tinker with new things.”

------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Theme 3: New credentialing systems will arise as self-directed learning expands

As they anticipate the appearance of effective new learning environments and advances in digital accountability systems, many of these experts believe fresh certification programs will be created to attest to workers’ participation in training programs and the mastery of skills. Some predict that many more workers will begin using online and app-based learning systems.

While the traditional college degree will still hold sway in 2026, more employers may accept alternate credentialing systems, as learning options and their measures evolve

Charlie Firestone, communications and society program executive director and vice president at The Aspen Institute, replied, “There will be a move toward more precise and better credentialing for skills and competencies, e.g., badging and similar techniques. Employers will accept these more as they prove probative. And online learning will be more prevalent, even as an adjunct to formal classroom learning. New industries such as green energy and telemedicine will increase new employment opportunities. Despite all of these measures, the loss of jobs from artificial intelligence and robotics will exceed any retraining program, at least in the short run.”

Sam Punnett, research officer at TableRock Media, wrote, “I suspect employers will recognize the new credentialing systems. Particularly those certificates awarded for studies in emerging disciplines (currently data science appears ‘all the rage’) and those that reflect an upgrade of previously acquired skills. Traditional credentials will continue to hold value, but I believe they will be considered in light of a candidates perceived ability in ‘learning how to learn.’ The four-year degree and subsequent graduate studies will continue to be less of a guaranty towards employment without work experience. … Certificates are being viewed more favourably, and many universities are lagging in their connection between their pedagogies and working-world requirements.”

William J. Ward, a university communications professor, @DR4WARD, commented, “Higher Education is doing a poor job of preparing students with the skills they need to succeed in the workforce. Online and credentialing systems are more transparent and do a better job on delivering skills. People with new types of credentialing systems are seen as more qualified than traditional four-year and graduate programs.”

The proof of competency may be in the real-world work portfolios

Many workplaces place a higher value on real-world work portfolios than they do on a degree or certification, yet their hiring systems – including AI bots programmed to scan resumés – still use the commonly accepted credentials as a basis for interviewing candidates. Some respondents hope to see change.

Schools today turn out widget makers who can make widgets all the same. They are built on producing single right answers rather than creative solutions.

JEFF JARVIS

A software engineering and system administration professional commented, “The reliability of the traditional educational system is already being questioned – in some fields it’s considered common sense that certifications and degrees mean little, and that a portfolio, references, and hands-on interviews are much more important for assessing a candidate’s ability. The unfortunate reality is that many HR departments still post job listings saying degrees and certifications are required, as a way of screening candidates. Both of those cost a lot of money, and neither mean a lot for a candidate’s competence. I hope this will change (both job listings and quality of degrees/certifications), but don’t see it happening soon.”

Meryl Krieger, career specialist at Indiana University, Bloomington’s Jacobs School, replied, “Credentialing systems will involve portfolios as much as resumés – resumés simply are too two-dimensional to properly communicate someone’s skillset. Three-dimensional materials – in essence, job reels – that demonstrate expertise will be the ultimate demonstration of an individual worker’s skills. I see credentialing as a piece of a very complex set of criteria; these will also incorporate an individual’s ability to communicate and work with teams (huge in employer requests for new employees), which can more readily be documented and tracked through online portfolio tools than through traditional resume formats. Thus, the educational and training programs of the future will become (in their best incarnations) sophisticated combinations of classroom and hands-on training programs. The specific models will necessarily be responding to individual industry requirements.”

Jeff Jarvis, a professor at the City University of New York Graduate School of Journalism, wrote, “Schools today turn out widget makers who can make widgets all the same. They are built on producing single right answers rather than creative solutions. They are built on an outmoded attention economy: Pay us for 45 hours of your attention and we will certify your knowledge. I believe that many – not all – areas of instruction should shift to competency-based education in which the outcomes needed are made clear and students are given multiple paths to achieve those outcomes, and they are certified not based on tests and grades but instead on portfolios of their work demonstrating their knowledge.”

While the first three themes found among the responses to this canvassing were mostly hopeful about advances in education and training for 21st‑century jobs, a large share of responses from top experts reflect a significant degree of pessimism for various reasons. Some even say the future of jobs for humans is so baleful that capitalism may fail as an economic system. The next themes and subthemes examine these responses.

------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Theme 4: Training and learning systems will not meet 21st‑century needs by 2026

A large share of respondents predicted that online formats for knowledge transfer will not advance significantly in the next decade. The 30% who expressed pessimism were often deeply doubtful about the capabilities of current education systems to adapt, to pivot to respond to new challenges as quickly as necessary. Interestingly, being able to adapt and respond to looming challenges was seen by nearly everyone in this canvassing as one of the most highly prized future capabilities; these respondents especially agree that it is important, and they say that our human institutions – government, business, education – are not adapting efficiently and are letting us down. Many of them say that current K-12 or K-16 education programs are incapable of making adjustments within the next decade to serve the shifting needs of future jobs markets.

Among the other reasons listed by people who do not expect these kinds of transformative advances in job creation and job skill upgrading:

It may not be possible to train workers for future skills, for many reasons, including that there will not be any jobs to train them for or that jobs change too quickly.

There is no “political will,” nor is there evidence leaders will provide funding, for mass-scale improvement in training. Several observed that if education advances cannot be monetized with the appropriate profit margin, they are not moved forward.

Many workers are incapable of taking on or unwilling to make the self-directed sacrifices they must to adjust their skills.

The “soft” skills, capabilities and attitudes respondents assume will be necessary in future workers are difficult to teach en masse or at all, and they question how any teaching scheme can instill such sophisticated traits in large numbers of workers.

Some among the 70% of respondents who are mostly optimistic about the future of training for jobs also echoed one or more of the points above – mentioning these tension points while hoping for the best. Following are representative statements tied to these points and more from all respondents.

Within the next decade, education systems will not be up to the task of adapting to train or retrain people for the skills likely to be most prized in the future

Thomas Claburn, editor-at-large at Information Week, wrote, “I’m skeptical that educational and training programs can keep pace with technology.”

Traditional models train people to equate what they do with who they are (i.e., what do you want to be when you grow up) rather than to acquire critical thinking and flexible skills and attitudes that fit a rapidly changing world.

PAMELA RUTLEDGE

Andrew Walls, managing vice president at Gartner, wrote, “Barring a neuroscience advance that enables us to embed knowledge and skills directly into brain tissue and muscle formation, there will be no quantum leap in our ability to ‘up-skill’ people. Learning takes time and practice, which means it requires money, lots of money, to significantly change the skill set of a large cohort.”

B. Remy Cross, assistant professor of sociology, Webster University, commented, “Lacking a significant breakthrough in machine learning that could lead to further breakthroughs in adaptive responses by a fully online system, it is too hard to adequately instruct large numbers of people in the kinds of soft skills that are anticipated as being in most demand. As manufacturing and many labor-intensive jobs move overseas or are fully mechanized, we will see a bulge in service jobs. These require good people skills, something that is often hard to train online.”

John Bell, software developer and teacher at Dartmouth College, replied, “Even today, access to information is not the limiting factor in skills education for anyone who can go online. … While there have been generational gains in the developments of online communities, a large-scale educational experience (either MOOC or on-demand broadcasts) will not be able to duplicate that.”

Stowe Boyd, managing director of Another Voice and a well-known thinker on work futures, discussed the intangibles of preparing humans to partner with AI and bot systems: “While we may see the creation and rollout of new training programs,” he observed, “it’s unclear whether they will be able to retrain those displaced from traditional sorts of work to fit into the workforce of the near future. Many of the ‘skills’ that will be needed are more like personality characteristics, like curiosity, or social skills that require enculturation to take hold. Individual training – like programming or learning how to cook – may not be what will be needed. And employers may play less of a role, especially as AI- and bot-augmented independent contracting may be the best path for many, rather than ‘a job.’ Homesteading in exurbia may be the answer for many, with ‘forty acres and a bot’ as a political campaign slogan of 2024.”

Luis Miron, a distinguished university professor and director of the Institute for Quality and Equity in Education at Loyola University in New Orleans, wrote, “Bluntly speaking, I have little confidence in the educational sector, K-16, having the capacity and vision to offer high-quality online educational programs capable of transforming the training needs of the wider society. The most important skills are advanced critical thinking and knowledge of globalization affecting diverse societies – culturally, religiously and politically.”

Pamela Rutledge, director of the Media Psychology Research Center, wrote, “The core assumptions driving educational content are not adapting as fast as the world is changing. Traditional models train people to equate what they do with who they are (i.e., what do you want to be when you grow up) rather than to acquire critical thinking and flexible skills and attitudes that fit a rapidly changing world. We have traditional institutions invested in learning as a supply-side model rather [than] demand-side that would create proactive, self-directed learners. This bias impacts the entire process, from educators to employers. It is changing, but beliefs are sticky and institutions are cumbersome bureaucracies that are slow to adapt. New delivery systems for skills related to technology will be more readily accepted than traditional ones because they avoid much of the embedded bias. … Successful education models will begin developing ‘mixed methods’ to leverage technology with traditional delivery and rewrite certification processes with practice-relevant standards.”

Justin Reich, executive director at the MIT Teaching Systems Lab, observed, “There will continue to be for-profit actors in the sector, and while some may offer choice and opportunity for students, many others will be exploitative, with a great[er] focus on extracting federal grants and burdening students with debt than actually educating students and creating new opportunities.”

Show me the money: Many doubts hinge upon lack of political will and necessary funding

John Paine, a business analyst, commented, “The competing desires 1) to make educational activity available to all and 2) to monetize the bejeezus out of anything related to the internet will limit the effectiveness of any online learning systems in a more widespread context.”

danah boyd, founder of Data & Society, commented, “I have complete faith in the ability to identify job gaps and develop educational tools to address those gaps. I have zero confidence in us having the political will to address the socio-economic factors that are underpinning skill training. For example, companies won’t pay for reskilling – and we don’t have the political power to tax them at the level needed for public investment in reskilling. Furthermore, we have serious geographic mismatches, underlying discriminatory attitudes, and limited opportunities for lower- [to] mid-level career advancement. What’s at stake are not simply skills gaps – it’s about how we want to architect labor, benefits and social safety nets. And right now, we talk about needing to increase skills, but that’s not what employers care about. It just sounds nice. When computer science graduates from CUNY and Howard University can’t get a job, what’s at stake is not skills training.”

Some people are incapable of or uninterested in self-directed learning

Among the future worker capabilities with the highest value in these respondents’ eyes are the ability to adapt, or “pivot,” and the motivation to up-skill as needed. Many respondents emphasized that the most crucial skill is that people have to learn how to learn and be self-motivated to keep learning.

My biggest concern with self-directed learning is that it requires a great deal of internal motivation. And I am not confident that individuals will find their way …

DAVID BERSTEIN

David Bernstein, a former research director, wrote, “The most important skills needed to succeed in the workplace will be flexibility and the ability to adapt and continuously learn. … My biggest concern with self-directed learning is that it requires a great deal of internal motivation. And I am not confident that individuals will find their way, just as those who enter college today don’t know what they want to be when they grow up, often until after they graduate. So everyone will still need some basic skills (interpersonal communications, basic arithmetic, along with some general culture awareness) [so] they can have that flexibility. … Any 3-year-old can use their parent’s smartphone or tablet without reading the manual. What I worry about is how well they will adapt when they are 35 or 55.”

Calton Pu, professor and junior chair in software at the Georgia Institute of Technology, wrote, “The most important skill is a meta-skill: the ability to adapt to changes. This ability to adapt is what distinguished Homo sapiens from other species through natural selection. As the rate of technological innovation intensifies, the workforce of the future will need to adapt to new technology and new markets. The people who can adapt the best (and fastest) will win. This view means that any given set of skills will become obsolete quickly as innovations change the various economic sectors: precision agriculture, manufacturing 4.0, precision medicine, just to name a few. Therefore, the challenge is not only to teach skills, but also how to adapt and learn new skills. Whether the traditional programs or new programs will be better at teaching adaptive learning remains to be seen.”

Cory Salveson, learning systems and analytics lead at RSM US, responded, “The nature of work today, and in future, is such that if people want to keep increasingly scarce well-paying jobs, they will need to educate themselves in an ongoing manner for their whole lives.”

Some of these experts say those who aren’t motivated to continue to learn and grow will be left behind.

Scott Amyx, CEO of Amyx+, said online training is advancing and will continue to evolve, but, “The education system is at an inflection point. Many ambitious federal and state programs have fizzled, to produce dismal to no statistical change in the caliber of K-12 education. … It’s those less-educated and less-skilled who are most sensitive to technological displacement. Online mediums and self-directed approaches may be limited in effectiveness with certain labor segments unless supplemented by human coaching and support systems.”

Beth Corzo-Duchardt, a professor at Muhlenberg College, replied, “Self-directed study is [a] variable that changes the alchemy of teaching and learning. It is true that most online courses require self-direction. Indeed, when I advise students, I don’t recommend that students take online courses unless they have demonstrated an aptitude for self-direction. But in-person courses may also be self-directed. This works well for some students but not others. Students who are self-directed often have had a very good foundational education and supportive parents. They have been taught to think critically and they know that the most important thing you can learn is how to learn. And they are also are more likely to come from economic privilege. So, not only does the self-direction factor pose a problem for teaching at scale, the fact that a high degree of self-direction may be required for successful completion of coursework towards the new workforce means that existing structures of inequality will be replicated in the future if we rely on these large-scale programs.”

------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Theme 5: Jobs? What jobs? Technological forces will fundamentally change work and the economic landscape

Among the 30% of respondents who said they did not think things would turn out well in the future were those who said the trajectory of technology will overwhelm labor markets, killing more jobs than it creates. They foresee a society where AI programs and machines do most of the work and raise questions about people’s sense of identity, the socio-economic divisions that already distress them, their ability to pay for basic needs, their ability to use the growing amount of “leisure time” constructively and the impact of all of this on economic systems. It should also be noted that many among the 70% who expect positive change in the next decade also expressed some of these concerns.

There will be many millions more people and millions fewer jobs in the future

The problem of future jobs is not one of skills training – it is one of diminishing jobs. How will we cope with a workforce that is simply irrelevant?

JENNIFER ZICKERMAN

Cory Doctorow, activist-in-residence at MIT Media Lab and co-owner of Boing Boing (boingboing.net), responded, “It’s an article of faith that automation begets more jobs [than it] displaces (in the long run); but this is a ‘theory-free’ observation based on previous automation booms. The current automation is based on ‘general purpose’ technologies – machine learning, Turing complete computers, a universal network architecture that is equally optimized for all applications – and there’s good reason to believe that this will be more disruptive, and create fewer new jobs, than those that came before.”

Glenn Ricart, Internet Hall of Fame member and founder and chief technology officer of US Ignite, said, “Up to the present time, automation largely has been replacing physical drudgery and repetitive motion – things that can and should improve the quality of people’s work lives. But in the next decade or two, there is likely to be a significant amount of technological innovation in machine intelligence and personal assistants that takes a real swipe out of the jobs we want humans to have in education, health care, transportation, agriculture and public safety. What are the ‘new jobs’ we want these people to have? If we haven’t been able to invent them in response to international trade pacts, why are we sure we will be able to create them in the future?”

Richard Stallman, Internet Hall of Fame member and president of the Free Software Foundation, commented, “I think this question has no answer. I think there won’t be jobs for most people a few decades from now, and that’s what really matters. As for the skills for the employed fraction of advanced countries, I think they will be difficult to teach. You could get better at them by practice, but you couldn’t study them much.”

Jennifer Zickerman, an entrepreneur, commented, “The problem of future jobs is not one of skills training – it is one of diminishing jobs. How will we cope with a workforce that is simply irrelevant?”

Capitalism itself is in real trouble

The question isn’t how to train people for nonexistent jobs, it’s how to share the wealth in a world where we don’t need most people to work.

NATHANIEL BORENSTEIN

Nathaniel Borenstein, chief scientist at Mimecast, replied, “I challenge the premise of this question [that humans will have to be trained for future jobs]. The ‘jobs of the future’ are likely to be performed by robots. The question isn’t how to train people for nonexistent jobs, it’s how to share the wealth in a world where we don’t need most people to work.”

Paul Davis, a director based in Australia, predicted, “Whilst such programs will be developed and rolled out on a large scale, I question their overall effectiveness. Algorithms, automation and robotics will result in capital no longer needing labor to progress the economic agenda. Labor becomes, in many ways, surplus to economic requirements. This … shift will dramatically transform the notion of economic growth and significantly disrupt social contracts; labor’s bargaining position will be dramatically weakened. The nature of this change may require the world to shift to a ‘Post Economic Growth’ model to avoid societal dislocation and disruption.”

John Sniadowski, a systems architect, replied, “The skill sets which could have been taught will be superseded by AI and other robotic technology. By the time the training programs are widely available, the required skills will no longer be required. The whole emphasis of training must now be directed towards personal life skills development rather than the traditional working career-based approach. There is also the massive sociological economic impact of general automation and AI that must be addressed to redistribute wealth and focus life skills at lifelong learning.”

Tom Sommerville, agile coach, wrote, “Our greatest economic challenges over the next decade will be climate change and the wholesale loss of most jobs to automation. We urgently need to explore how to distribute the increasing wealth of complex goods and services our civilization produces to a populace that will be increasingly jobless in the traditional sense. The current trend of concentrating wealth in the hands of a diminishing number of ultra-rich individuals is unsustainable. All of this while dealing with the destabilizing effects of climate change and the adaptations necessary to mitigate its worst impacts.”

Some of these experts projected further out into the future, imagining a world where the machines themselves learn and overtake core human emotional and cognitive capacities.

Timothy C. Mack, managing principal at AAI Foresight, said, “In the area of skill-building, the wild card is the degree to which machine learning begins to supplant social, creative and emotive skill sets.”

Responses from additional key experts regarding the future of jobs and jobs training

This section features responses by several more of the many top analysts who participated in this canvassing. Following this wide-ranging set of comments on the topic, a much more expansive set of quotations directly tied to the set of four themes begins on Page 40.

‘There will be a parallel call for benefits, professional development and compensation that smooths out rough patches’ in an ‘on-demand labor life’

Baratunde Thurston, a director’s fellow at MIT Media Lab, Fast Company columnist and former digital director of The Onion, replied, “Online training and certification will grow significantly in part due to the high expense of formal higher education along with its declining payoffs for certain occupations. Why go $100,000 in debt for a four-year university, when you can take a more targeted course with more guaranteed income generation potential at the end? From the employer perspective, this type of learning will only grow. We are creating a system of on-demand labor akin to ‘cloud-based labor’ where companies ‘provision’ labor resources at will and release them at will, not by the year or month but by the job, labor unit, or small time unit, including minutes. The automation of human labor will grow significantly. And having a workforce trained in discrete and atomizable bits of skills will be seen as a benefit by employers. This of course is a terrible, soulless, insecure life for the workers, but since when did that really change anything? There will also be a parallel call for benefits, professional development, and compensation that smooths out the rough patches in this on-demand labor life, but such efforts will lag behind the exploitation of said labor because big business has more resources and big tech moves too fast for human-scale responses of accountability and responsibility. To quote Donald Trump, ‘Sad!’ ”

We will see much more personalized, adaptive forms of education

Doc Searls, journalist, speaker and director of Project VRM at Harvard University’s Berkman Klein Center for Internet & Society, wrote, “I don’t expect the evolution of work in the connected world to require ‘new educational and training programs.’ Instead, I expect we’ll see much more adaptive forms of education, especially of the self-made kind. Look at Linux and open-source development. The world runs on both now, and they employ millions of human beings. Many, or most, of the new open-source programmers building and running our world today are self-taught, or teach each other, to a higher degree than they are educated by formal schooling. Look at Khan Academy and the home-schooling movement, both of which in many ways outperform formal institutional education. The main qualification for programming work isn’t a degree. It’s proven capability. This model for employment of self and others will also spread to other professions. (By the way, I don’t like the term ‘job.’ It demeans work, and reduces the worker to a position in an org chart.) The great educator John Taylor Gatto, who won many awards for his teaching and rarely obeyed curricular requirements, says nearly all attempts to reform education make it worse. We are by nature learning animals. We are each also very different: both from each other and from who we were yesterday. As a society we need to take advantage of that, and nurture our natural hunger for knowledge and productive work while respecting and encouraging our diversity, a fundamental balancing feature of all nature, human and otherwise.”

‘We will likely see a radical economic disruption in education, using new tools and means’

Jeff Jarvis, professor at the City University of New York Graduate School of Journalism, wrote, “At a roundtable on the future convened by Union Square Ventures a few years ago, I heard this economic goal presented: We need to see the marginal cost of teaching another student fall to zero to see true innovation come to education, allowing change to occur outside the tax-based (and thus safe) confines of public education. I don’t think we’ll ever reach zero; MOOCs are not the solution! But we will likely see a radical economic disruption in education – using new tools and means to learn and certify learning – and that is the way by which we will manage to train many more people in many new skills.”

The current education system is perpetuating the shortage of talent

Cory Doctorow, activist-in-residence at MIT Media Lab and co-owner of Boing Boing (boingboing.net), responded, “There is, for the immediate and medium term, a huge shortage of IT talent, of course – especially security researchers and professionals. In part, this is driven by the legal and educational framework that takes a zero tolerance approach to the ‘hacking’ that kids historically engaged in on their way to becoming security researchers. If a kid today hacks her school’s censoring firewall to look at a blocked site, she is expelled (and possibly arrested), not streamed into an [Advanced Placement] computer science class. We also have a poorly constituted math curriculum for understanding ‘algorithms’ (which is really understanding the statistics of machine learning models). An earlier and more enduring focus on stats and statistical literacy – which can readily be taught using current affairs, for example, analyzing the poll numbers from elections, the claims made by climate change scientists, or even the excellent oral arguments in the Supreme Court Texas abortion law case – would impart skills that transferred well into IT, programming and, especially, security.”

The most important skill at the moment of the ‘Cambrian Explosion of robotics’ is adaptability

Amy Webb, futurist and CEO at the Future Today Institute, commented, “Gill Pratt, a former program manager of the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA), recently warned of a Cambrian Explosion of robotics. About 500,000 years ago, Earth experienced its first Cambrian Explosion – a period of rapid cellular evolution and diversification that resulted in the foundation of life as we know it today. We are clearly in the dawn of a new age, one that is marked not just by advanced machines but, rather, machines that are starting to learn how to think. Soon, those machines that can think will augment humankind, helping to unlock our creative and industrial potential. Some of the workforce will find itself displaced by automation. That includes anyone whose primary job functions are transactional (bank tellers, drivers, mortgage brokers). However, there are many fields that will begin to work alongside smart machines: doctors, journalists, teachers. The most important skill of any future worker will be adaptability. This current Cambrian Explosion of machines will mean diversification in our systems, our interfaces, our code. Workers who have the temperament and fortitude to quickly learn new menu screens, who can find information quickly, and the like will fare well. I do not see the wide-scale emergence of training programs during the next 10 years due to the emergence of smart machines alone. If there are unanticipated external events – environmental disasters, new pandemics and the like – that could devastate a country’s economy and significantly impact its workforce, which might catalyze the development of online learning opportunities.”

A lot of knowledge can be imparted by machines and doesn’t require ‘human interaction’

Mike Roberts, Internet Hall of Fame member and first president and CEO of the Internet Corporation for Assigned Names and Numbers (ICANN), responded, “MOOCs and related efforts are in their infancy, so ‘yes,’ there will [be] considerable expansion as more is learned about what works and what doesn’t work. These developments are contributing to a crisis of self-confidence in higher ed, where traditional scholarship is being challenged on many fronts, including the basic definition of ‘education.’ Human brains are complex, and it becomes tiresome to see simplistic approaches to education issues. Generally, an ‘educated’ person possesses a level of knowledge about the world that allows him or her to use analytical skills – induction, deduction, probability, etc. – to arrive at conclusions that guide behavior. The jury is very much out on the extent to which acquisition of knowledge and reasoning skills requires human interaction. We now have empirical evidence that a substantial percentage – half or more – can be gained through self-study using computer-assisted techniques. The path forward for society as a whole is strewn with obstacles of self-interest, ignorance, flawed economics, etc. If one believes in ‘the singularity,’ it doesn’t matter, because human-machine symbiosis will bury the problem!”

‘What should people know to be informed participants in a democracy?’

Judith Donath of Harvard University’s Berkman Klein Center for Internet & Society replied:

“A lot has been written about the need for STEM [science, technology, engineering and mathematics] education. Here I want to focus on other areas.

1) Teaching and Healing: As computers, robots and other machines take over many jobs, we need to reposition the social status of jobs that involve interpersonal care: day care, teachers, nurse, elderly, coach. The issue is not just training but cultural re-evaluation of teaching and healing as highly respected skills. While technology can assist with this work, we mustn’t lose sight of the importance of human connections as an end in and of themselves.

2) Craft and Repair: For the benefit of both the individual and the environment, we need to strongly support learning design, craft, building, repair. Few of us make anything we use – from the building we live in to the objects we own – and these things are mostly manufactured as cheaply as possible, to be easily bought, discarded, and bought again, in a process of relentless acquisition that often brings little happiness. Education here should be integrated into everyday life, not just for when one is ‘in school.’ E.g., much rental housing is in bad repair, with tenants waiting weeks, months, years for even simple fixes – a running toilet, broken lights, a hole in a wall. Very easily accessible learning for how to fix these things themselves (and making it economically rewarding, in the case of a common good) – is a simple, basic example of the kind of ubiquitous craft learning that at scale would be enormously valuable. Some of this can be taught online – a key component is also online coordination.

3) An Informed Citizen: What should people know, what skills should they have, to be informed participants in a democracy? Certainly science and technology are important, but we need to refocus liberal education, not ignore it. History, in all its complexity. Critical thinking – how to debate, how to recognize persuasive techniques, how to understand multiple perspectives, how to mediate between different viewpoints. Key skill: how to research, how to evaluate what you see and read.”

‘Learning in private is selfish. Public learning is becoming the norm.’

David Weinberger, a senior researcher at Harvard University’s Berkman Klein Center for Internet & Society, said, “Judging from what we’re seeing happening now on the web, it seems likely that many of [the innovative platforms] will be peer-to-peer. Sites like Stack Overflow for software engineers demonstrate a new moral sense that learning in private is selfish. Public learning is becoming the norm.”

Most of the focus will be on childhood education for the world

Brad Templeton, chair for computing at Singularity University, wrote, “We will see the start of these technologies, but they will not be widespread at the hard problem of adult retraining in 10 years. Instead, most focus will be on childhood education for the poorer sectors of the world. The most important skill, flexibility, won’t be taught easily this way, but must become a focus of K-12 education.”

Look at what MOOCs have done already

John Markoff, former senior writer at The New York Times, said, “We have now passed through the first generation of MOOCs, and a new generation of online learning technology is beginning to emerge. Udacity is a good example of the trajectory. Sebastian Thrun was one of the inventors of the MOOC concept. After starting a company to pursue the idea, he pivoted, focusing specifically on skill-oriented education that is coupled directly to the job market.”

The internet fosters innovation

Vint Cerf, vice president and chief internet evangelist at Google and an Internet Hall of Fame member, noted, “The internet can support remote training and learning. These need not be MOOCs. Even mobiles can be sources of education. I hope we will see more opportunities arising for sharing this kind of knowledge.”

The main teaching goal: ‘We will make you better than a robot. We let you cooperate with robots.’

Marcel Bullinga, trend watcher and keynote speaker @futurecheck, replied, “The future is cheap, and so is the future of education. I saw an ad already for $1,000 bachelor’s-level training – with an app, of course. Schools and universities will transform in the same way as shops have done in the past 10 years from analog/human-first to digital/mobile/AI-first. New online credential systems will first complement, then gradually replace the old ones. The skills of the future? Those are the skills a robot cannot master (yet). Leadership, design, human meta communication, critical thinking, motivating, cooperating, innovating. In my black-and-white moments I say: Skip all knowledge training in high schools. Main teaching goal: ‘We enable you to survive in an ever-changing world with ever-changing skills and not-yet-existing jobs of the future. We make you better than a robot. We let you cooperate with robots. We build your self-trust. We turn you into a decent, polite, social person. And most importantly, we do not mix education with religion – never.’”

Acceptance and quality of training programs ‘will map to existing systemic biases’

Anil Dash, entrepreneur, technologist, and advocate @AnilDash, predicted, “These credentials will start to become widespread, but acceptance and quality of the training programs will map to the existing systemic biases that inform current educational and career programs.”

The most essential deep learning will not come from online systems

Henning Schulzrinne, Internet Hall of Fame member and professor at Columbia University, wrote, “Training programs have had the problem that short-duration generic programs are often not very effective except as a way to incrementally add very specific skills (‘learn how to operate the new industry-specific tool X in a week’) to the existing repertoire. The subject-matter-specific part of a B.S. degree in a technical or scientific field takes at least two years, often more, and these are high-intensity, full-time years, often without other responsibilities such as family, mostly for students at an age where learning is still natural and easy. A large part of this time is spent not in a classroom but becoming fluent through monitored practice, including group work, internships and other high-intensity, high-interaction apprentice-like programs. It is hard to see how workers can afford to spend two years without income support while still fulfilling their ‘adult’ responsibilities such as taking care of their family or elderly parents. There are possibilities for adding limited skill sets to otherwise qualified workers, e.g., the ability to program in Python for somebody who already has an economics degree, increasing their ability to get their work done. The MOOC-style programs have shown themselves to be most effective for this ‘delta’ learning for practicing professionals, not turning a high school graduate into somebody who can compete with a college graduate.”

We may soon be at the point where ‘adaptive algorithms learn jobs faster than humans’

Jamais Cascio, distinguished fellow at the Institute for the Future, responded, “We will certainly see attempts to devise training and education to match workers to new jobs, but for the most part they’re likely to fall victim to two related problems. 1) The difficulty of projecting what will be the ‘jobs of the future’ in a world where the targets keep shifting faster and faster. Jobs that seem viable may fall victim to a surprising development in automation (see, for example, filmmaking); new categories of work may not last long enough to support large numbers of employees. 2) We’re in an era of general-purpose computing, which means that our systems are not physically or procedurally limited to a narrow type of work. Automation and semi-automation (e.g., self-checkout stands) don’t need to completely eliminate a job to make it unable to support large numbers of workers. As learning systems improve, we will soon (if we’re not already) be at a point where adaptive algorithms can learn new jobs faster than humans.”

‘Very unlikely’ that a new training regime will be successful

Kate Crawford, a well-known internet researcher studying how people engage with networked technologies, wrote, “We clearly need new educational and training programs to address the deepening precarity of the labor market. But to make it ‘successful,’ in that the right training could be developed to make it possible that everyone will have jobs, is very unlikely.”

New information flows will require new ways to think about education and learning

Paul Jones, clinical professor and director at the University of North Carolina, replied, “We learn more today by training and information sipping than in the past. Training is useful but not the end of education – only a kind of education. As for sipping: you need not know the name of every bear to know you should avoid bears. Yet the continual construction of knowledge and cultures requires more from us. So far, training formally as in Kahn Academy and Lynda.com are unarguably effective for continual updates for basic skills. No programmer or developer could keep up without the informal training of Stack Overflow. Wikipedia hasn’t destroyed bar trivia, but it has made a dent in our conversational expertise. Who played guitar lead on “All or Nothing”? No need for debate. A little information sip will let us know. We’re fine and informed – but not educated or learned. But what is left out? Collaborative construction of knowledge in new areas, deeper investigation into known areas, and the discovery of entirely new areas of knowledge. This is our challenge: how to create wisdom from knowledge, not just jobs from training and information.”

‘We need to think about co-evolving work and workers’