Date: 2024-12-21 Page is: DBtxt003.php txt00014532

Energy / Oil

Market Supply and Demand

Peak oil demand and long-run oil prices ... BP chief economist Spencer Dale and Bassam Fattouh, director of The Oxford Institute for Energy Studies, argue that this focus seems misplaced.

Burgess COMMENTARY

Peter Burgess

Peak oil demand and long-run oil prices

The point at which oil demand will peak has long been a focus of debate. BP chief economist Spencer Dale and Bassam Fattouh, director of The Oxford Institute for Energy Studies, argue that this focus seems misplaced. The significance of peak oil is that it signals a shift from an age of perceived scarcity to an age of abundance – and with it, a likely shift to a more competitive market environment

Global oil markets are changing dramatically.

The advent of electric vehicles and the growing pressures to decarbonise the transportation sector means that oil is facing significant competition for the first time within its core source of demand. This has led to considerable focus within the industry and amongst commentators on the prospects for peak oil demand – the recognition that the combined forces of improving efficiency and building pressure to reduce carbon emissions and improve urban air quality is likely to cause oil demand to stop increasing after over 150 years of almost uninterrupted growth.

At the same time, the supply side of the oil market is experiencing its own revolution. The advent of US tight oil has fundamentally altered the behaviour of oil markets, introducing a new and flexible source of competitive oil. More generally, the application of new technologies, especially digitalisation in all its various guises, has the potential to unlock huge new reserves of oil over the next 20 to 30 years.

The prospect of peak oil demand, combined with increasingly plentiful supplies of oil, has led many commentators to conclude that oil prices are likely to decline inextricably over time. If the demand for oil is drying up and the world is awash with oil, why should oil prices be significantly higher than the cost of extracting the marginal barrel? The days of rationing and scarcity premiums must surely be numbered?

These developments are important. Growth in oil demand is likely to slow gradually and eventually peak. And plentiful supplies of oil are likely to alter fundamentally the behaviour of oil producing economies.

However, this paper argues the current focus on the changing nature of the oil market is largely misplaced.

ee-2018-16x9-grad.jpg

Energy Outlook – 2018 edition

Bob Dudley and Spencer Dale will launch the new report at 2.30pm GMT on 20 February 2018. Register for the live webcast now

Quick links

Peak oil demand and long-run prices

Peak oil demand

From scarcity to abundance

Long-run oil prices

Conclusions

Download 'Peak oil demand and long-run oil prices'

(PDF 472.3 KB)

Much of the popular debate is centred around when oil demand is likely to peak. A cottage industry of oil executives and industry experts has developed trading guesses of when oil demand will peak: 2025, 2035, 2040?1 This focus on dating the peak in oil demand seems misguided for at least two reasons.

First, no one knows: the range of uncertainty is huge. Small changes in assumptions about the myriad factors determining oil demand, such as GDP growth or the rate of improvement in vehicle efficiency, can generate very different paths.

Second, and more importantly, this focus on the expected timing of the peak attaches significance to this point as if once oil stops growing it is likely to trigger a sharp discontinuity in behaviour: oil consumption will start declining dramatically or investment in new oil production will come to an abrupt halt. But this seems very unlikely. Even after oil demand has peaked, the world is likely to consume substantial quantities of oil for many years to come. The comparative advantages of oil as an energy source, particularly its energy density when used in the transport system, means it is unlikely to be materially displaced for many decades. And the natural decline in existing oil production means that significant amounts of investment in new oil production is likely to be required for the foreseeable future.

The date at which oil demand is likely to peak is highly uncertain and not particularly interesting.

Rather, the importance of ‘peak oil demand’ is that it signals a break from the paradigm that has dominated oil markets over the past few decades.

In the past, any mention of peak oil would have been interpreted as a reference to peak oil ‘supply’: the belief that there was a limited supply of oil and that as oil became increasing scarce, its price would tend to rise. This basic belief has had an important influence on oil markets since the 1970s and before. Oil producing countries rationed their oil supplies safe in the belief that if they didn’t produce a barrel of oil today they could produce it tomorrow, potentially at a higher price. Oil companies spent huge sums of money exploring and securing oil resources that were expected to become increasingly harder and more expensive to find.

Peak oil demand signals a break from a past dominated by concerns about adequacy of supply. A shift in paradigm: from an age of scarcity (or, more accurately, ‘perceived’ scarcity) to an age of abundance, with potentially profound implications for global oil markets as they become increasingly competitive, and for major oil producing countries as they reform and adjust their economies for an age in which they can no longer rely on oil revenues for the indefinite future.

One key implication of this paradigm shift is its impact on long-run price trends. The move to oil abundance is indeed likely to herald a more competitive market environment. But the assumption that oil prices will be determined simply by the cost of extracting the marginal barrel of oil risks ignoring an important aspect of global oil production. Many of the world’s major oil producing economies, with some of the largest proven reserves, rely very heavily on oil revenues to finance other aspects of their economies. The current structure of these economies would be unsustainable if oil prices were set close to the cost of extraction. Many oil producers would be forced to run large and persistent fiscal deficits or to cut back sharply on social provisions, which, in turn, would likely have knock on implications for global oil production and prices.

The argument is not that large oil producers cannot change the structure of their economies: the age of abundance means that structural reform to reduce oil dependency is more important than ever2. But history has shown that economic reform and diversification can be a long and challenging process. As such, the pace and extent of that reform process is likely to have an important bearing on oil prices over the next 20 or 30 years. It is not enough simply to consider the marginal cost of extraction, developments in these “social costs” of production are also likely to have an important bearing on oil prices over the foreseeable future.

The rest of the paper is structured as follows. The next section considers the outlook for oil demand and notes that under many alternative scenarios the world is likely to need significant amounts of oil for the foreseeable future. Section 3 examines the challenges posed by this shift in oil paradigm – from scarcity to abundance – for major oil producing economies and how they might respond; while Section 4 discusses the determination of longer-run oil prices in an age of abundance. Section 5 concludes.

Section 2: Peak oil demand

The broad consensus amongst energy commentators and forecasters is that global oil demand is likely to continue growing for a period, driven by rising prosperity in fast-growing developing economies. But that pace of growth is likely to slow overtime and eventually plateau, as efficiency improvements accelerate and a combination of technology advances, policy measures and changing social preferences lead to an increasing penetration of other fuels in the transportation sector. Some projections show oil demand peaking during the period they consider, others beyond their forecast horizons.

The aim of this section is not to propose a particular path for oil demand or to argue that one projection is more plausible than another. Rather it is simply to highlight two points:

the point at which oil demand is likely to peak is very uncertain and depends on many assumptions;

even once oil demand has peaked, consumption is unlikely to fall very sharply – the world is likely to consume significant amounts of oil for many years to come.

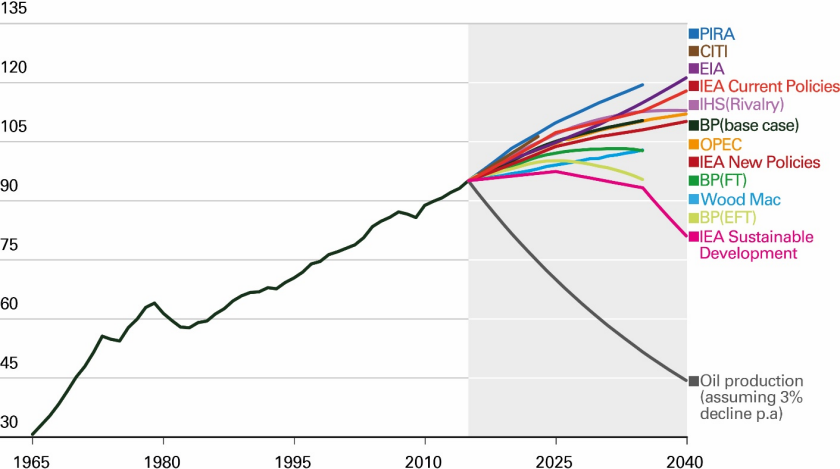

Chart 1 shows a range of forecast for oil demand over the next 25-30 years from a variety of public and private sector organisations.

Chart 1 – World oil demand (Mb/d)

peak-oil-chart-1-world-oil-demand-bp.png

There is wide range of estimates of the point at which oil demand is likely to peak. Some projections suggest global oil demand could peak soon after 2025, others expect demand to continue to grow out to 2040 and beyond. Indeed, different projections from the same organisation can point to quite different estimates depending on the assumptions used. For example, the IEA’s Sustainable Development scenario, which is predicated on a sharp tightening in climate policies, suggests oil demand may peak in the mid-2020s, whereas its “New Policies” scenario, which envisages a less sharp break in environmental policies, points to demand continuing to grow in 2040. A comparison of BP’s “Even Faster Transition” case with its base case points to a similar difference3. BP’s Energy Outlook also highlights how relatively small differences in assumptions about GDP growth or improvements in vehicle efficiency can radically shift the likely timing of the peak in demand.

The point here is that any estimate of when oil demand will peak is highly dependent on the assumptions underpinning it: slight differences in those assumptions can lead to very different estimates. Beware soothsayers who profess to know when oil demand will peak.

Chart 1 also illustrates that even those projections that predict oil demand will peak during their forecast period, do not envisage a sharp drop off in demand. The vast majority of the projections in Chart 1 expect the level of oil demand in 2035 or 2040 to be greater than it is today. Even those projections which suggest that oil demand may peak relatively early, such as the IEA Sustainable Development scenario, do not see a very sharp drop off in oil demand. The Sustainable Development scenario considers a scenario in which climate policies tighten sufficiently aggressively for carbon emissions to decline at a rate thought to be broadly consistent with achieving the goals set out at the Paris COP21 meetings. But even if this case, global oil demand is projected to be above 80 Mb/d in 2040, compared with 95 Mb/d today.

The key point here is that inherent advantages of oil as an energy source, particularly its energy density when used in the transport sector, means that the eventual peaking in oil demand is not expected to trigger a significant discontinuity or sharp fall in demand.

Moreover, the persistent decline in existing oil production means that significant investments in new oil production are needed just to maintain existing levels of production. Chart 1 includes an illustrative path for global oil production assuming that, as from today, no new investments are made and existing levels of production decline at a rate of 3% per year4. This implies a huge and ever widening gap between oil supply and the demand profiles. Under almost any scenario, the world is likely to require significant amounts of investment in new oil production for many years to come.

Recent developments in US oil demand tell a similar story. As shown in Chart 2, US oil demand peaked in 2005. Over the subsequent 8 years it declined at an average rate of around 1.0% per year, far slower than average decline rates for oil production. Moreover, since oil prices fell in 2014, US oil demand has begun to grow again and, if prices remain low for the next few years, could potentially exceed its previous peak. Indeed, US gasoline consumption reached its highest ever level in 2016 after falling for much of the previous 10 years.

Chart 2 – US oil and gasoline demand (Mb/d)

peak-oil-chart-2-us-oil-and-gasoline-demand-bp.png

* BP Statistical Review of World Energy 2017

** US Energy Information Administration, August 2017

The response of US oil demand to the recent period of low prices highlights an important issue when considering the likely profile of demand once global oil demand peaks. If the peaking in oil demand (or even just the prospect of peaking) causes prices to fall, this is likely to trigger a so-called “rebound effect”, in which falling prices stimulate higher demand.

As the US experience shows, these price effects are powerful and, at least for a period, can offset the underlying forces causing demand growth to slow, potentially leading to multiple peaks in demand5.

In summary, the point at which oil demand peaks is uncertain and sensitive to the assumptions used. Moreover, there is little evidence or reason to believe that the peak in oil demand, whenever it happens, will trigger a sharp discontinuity in either oil demand or investment spending. Or even that the peak in oil demand will be unique.

Section 3: From scarcity to abundance

Rather, the real significance of peak oil demand is that it signals a shift in paradigm from an age of (perceived) scarcity to an age of abundance. The conventional wisdom that dominated oil market behaviour over the past few decades, based around the notion of peak oil ‘supply’ and the belief that oil would become increasingly scarce and valuable over time, has been debunked6.

Over the past 35 years or so, for every barrel of oil consumed, two have been added to estimates of Proved Oil Reserves7. In its recent Outlook8, BP estimated that based on known oil resources and using only today’s technology, enough oil could be produced to meet the world’s entire demand for oil out to 2050, more than twice over! And future oil discoveries and improvements in technology are likely to only increase that abundance. The world isn’t going to run out of oil. Rather, it seems increasingly likely that significant amounts of recoverable oil will never be extracted.

The recognition that there is an abundance of oil is likely to trigger profound changes in global oil markets and the behaviour of oil producing economies, although the pace at which these changes take hold is a key source of uncertainty.

Most fundamentally, it is likely to cause global oil markets to become increasingly competitive. Over the past few decades – during the age of (perceived) scarcity – the oil market hasn’t behaved like a normal market. In particular, high-cost producers have been able to exist and compete alongside low-cost producers, even though high-cost oil is many times more expensive to produce. The laws of competitive markets, in which high-cost producers are driven out of the market, haven’t applied.

The reason is because owners of large, low-cost resources have until now effectively rationed their supplies of oil: rather than using their competitive advantage to maximise market share, they have preserved their resources for the future. This made sense during the age of scarcity, since concerns about peak supply suggested the value of these oil resources was likely to increase over time. Moreover, rationing supplies in this way provided a clear and transparent way of managing a country’s oil such that it was distributed fairly across future generations. A high reserves-to-production ratio – implying a country could continue producing oil at the same rate for 80, 90, 100+ years – was a sign of both strength and intergenerational fairness.

But the shift to an age of abundance changes all that. Faced with the possibility that significant amounts of recoverable oil may never be extracted, low-cost producers have a strong incentive to use their comparative advantage to squeeze out high-cost producers and gain market share – just as with any other competitive market. Moreover, if some oil may never be extracted, a high reserves-to-production ratio is no longer such a sign of strength. Better to have money in the bank than oil in the ground. This suggests that the oil market is likely to become increasingly competitive over time as producers fight for market share.

A corollary of this increasing competitiveness is that the distribution of economic rents within global oil markets is likely to shift. In particular, the high rents enjoyed by resource owners are likely to decline, with consumers benefitting as a result. In particular, to gain market share, low-cost producing economies will need to adopt a “higher volume, lower price” strategy to the benefit of oil consumers. In response, owners of higher-cost resources will need to offer increasingly attractive contracts and fiscal terms to ensure their oil remains competitive and able to attract the private-sector investment needed to extract it.

But the forces and dynamics prompted by this shift to an age of abundance and more competitive oil markets are likely to pose significant challenges to major oil producing countries and, as such, may take some time before they have their full effect.

At one level, there is a significant operational issue. If a low-cost producer wishes to adopt a “higher volume, lower price” strategy they will need to increase their production capacity. This is a major undertaking. For a country to increase their production from say 3 Mb/d to 6 Mb/d would take tens of billions of dollars and probably several decades. A change in strategy from rationing to maximising market share is costly, requiring huge investments, and cannot be implemented overnight9.

Even more challenging, major oil producers will need to restructure their economies. The sensitivity of oil prices to even relatively small shifts in supply means that adopting a “higher volume, lower price” strategy is likely to lead to a drop in oil revenues, particularly so if a number of producers adopt a similar strategy around the same time.

If they can no longer rely on oil revenues to provide their main source of income for the indefinite future, economies are likely to seek to diversify, developing other industries and productive activities. The Vision 2030 plan announced last year by Saudi Arabia is perhaps the most prominent example of a major oil producer responding to the changing environment – to the shift in paradigm – and starting to prepare their economy for the challenges posed by an age of abundance. But we know from history that deep and lasting economic diversification of this nature can be a long and challenging process.

Moreover, many oil producers may take a long time to develop alternative industries and activities that are as profitable as extracting low-cost oil. The difficulty of finding alternative sources of earning means the shift in oil paradigm may represent a reduction in wealth for many major oil producing economies, requiring an eventual adjustment in living standards.

For countries with a floating exchange rate, the depreciation of their exchange rate as the perceived value of their oil resources is marked down means that some of the required adjustment in living standards will happen quasi-automatically as imported goods and services become more expensive. The sharp devaluation of the Russian rouble following the oil price fall in 2014 is a good example of this. But for those countries with some form of pegged exchange rate system (as, for example, is the case for most countries in the Middle East), much of the burden will initially be borne by the country’s central finances and reserves, and so will be dependent on how and when the authorities choose to distribute that burden across the population more generally.

Importantly, the success that major oil producing countries have in reforming their economies and the pace at which they adjust living standards is likely to have an important bearing on the evolution on oil prices over the next 20-30 years.

Section 4: Long-run oil prices

The traditional textbook approach to oil price determination is based around the assumption that oil is an exhaustible resource, such that the world will eventually run out of oil. In these textbook models, oil commands a premium, over and above its immediate economic value, reflecting the perceived scarcity of oil and the presumption that this scarcity will intensify overtime.

The canonical Hotelling model10, named after the pioneering work of British economist Harold Hotelling, posited that a resource owner should extract their oil such that the value of their oil resources rose in line with the real interest rate. The intuition underpinning this result follows straightforwardly from the recognition that a resource owner should be indifferent between extracting oil today and investing the proceeds at the real interest rate versus the alternative of extracting oil tomorrow. The key economic assumption underlying the Hotelling result is that the fixed supply of oil means it could be treated akin to a financial asset, whose value would rise overtime as it became increasingly scarce.

But in an age of abundance, in which the world is likely to never run out of oil, the key assumptions underpinning this pricing approach no longer hold. What will determine oil prices over the next 20-30 years as we move from (perceived) scarcity to abundance and global oil markets become increasingly competitive?

As argued in Section 2, it seems likely that the world will demand significant amounts of oil for several decades to come. The key issue is not so much a lack of demand, but rather at what price the world’s major oil producing countries are able to supply 80/90/100 Mb/d of oil on a sustainable basis over the next 20 or 30 years?

Conventional economics would suggest that as global oil markets become increasing competitive, the oil price should tend towards the cost of producing the marginal barrel of oil. Estimates by Rystad Energy suggest that, in 2017, the average total cost of oil produced by the five major Middle-Eastern oil producers (Saudi Arabia, UAE, Iran, Iraq and Kuwait), who account for around 30% of world production, was less than $10. Likewise, Rystad estimate that around 40% of the world’s oil supplies in 2017 were produced at an average cost of less than $15 per barrel.

These estimates of the physical cost of production might suggest that, as global markets become increasingly competitive, and low-cost producers gain market share, the (real) oil price will drift inextricably lower. In particular, that oil prices will tend towards the cost of extracting the marginal barrel of oil.

But this focus on extraction costs ignores the fact that many of the world’s major oil producers depend on oil revenues to finance other aspects of their economies, such as health, education, public sector employment etc. As a result, the oil price needed to maintain the political and economic structure of these economies is far higher than simply the physical cost of extraction. There is an additional “social cost” of production that also needs to be taken into account when considering the longer-run evolution of oil prices. The argument here is not that the market price will always be sufficient to cover social costs in all oil producing economies. But simply that these social costs will have an important bearing on where oil prices stabilise in the long run and so need to be considered as well as the physical costs of production.

One very imperfect proxy for this social cost of production is to compare the physical cost of production with estimates of fiscal break-even prices, ie estimates of the level of oil prices needed to ensure that an economy’s fiscal deficit is in balance. For example, the IMF estimate that in 201611, the five major Middle-Eastern oil producers had an average fiscal break-even price of around $60 p/b, compared with estimates of an average (physical) cost of production of around $10.

Inferring an estimate of these social costs of production from fiscal break-even prices is fraught with difficulties. Estimates can vary significantly depending on the precise definitions and assumptions used. Moreover, estimates can vary substantially from year-to-year for a variety of cyclical factors, which may not reflect changes in the sustainable structure of an economy. For example, in a period of low oil prices, countries highly dependent on oil revenues may cut back on various infrastructure projects and other forms of investment spending causing their fiscal break-even price to fall in the short run. But many of these cuts may not be sustainable in the longer-run, which is what matters when considering the determination of oil prices in the medium term. In addition, fiscal break-even prices consider the level of prices required to achieve a measure of only internal balance within oil producing economies. The long-run sustainability of an oil producer also depends on the level of oil prices needed to ensure external balance, in terms of their current account deficit12.

Even so, fiscal break-even prices do provide a rough sense of the order of magnitude of the social costs of production, and suggest that for many of the world’s major oil producers the social cost of production is much greater than the physical cost.

The size of these social costs is of course simply a consequence of these economies being highly concentrated on the oil sector. As the economies diversify, the social costs should naturally decline as the economy is supported by a broader economic base. But as noted earlier, economic diversification is not likely to happen quickly, and so social costs of production in many of the world’s major oil producing economies are likely to remain material for a sustained period.

The size and persistence of these social costs have potentially important implications for the sustainable level of oil prices over the next 20 to 30 years.

In particular, a low-cost oil producer cannot sustainably seek to gain market share by adopting a “higher volume, lower price” strategy if it requires selling oil at a price below its total cost of production (including social costs). If the oil price doesn’t cover an economy’s total costs, it implies that some aspect of the economy is unsustainable.

In the short run, this instability is likely to manifest in large and persistent fiscal deficits, causing reserves to run down and debt to increase. It is quite possible – indeed in many circumstances desirable – for oil producing economies to run fiscal deficits during periods of temporary weakness in oil prices. Reserves can be rebuilt once prices recover and it is potentially very costly to make significant adjustments in government spending or the real economy in response to short-run, cyclical price fluctuations.

But fiscal deficits cannot be sustained indefinitely. Creditors are likely to become increasingly unwilling to lend money to economies that are unable to reform sufficiently to bring total production costs below the oil price in the foreseeable future. The alternative strategy of transferring the burden onto the general public by reducing levels of support and welfare is likely to be deeply unpopular.

It seems unlikely that oil prices will stabilise around a level in which many of the world’s major oil producing countries are either running large and persistent fiscal deficits or reducing levels of social support. At some point, the potential for ensuing socio-economic tensions could start to disrupt oil production and so cause oil prices to rise.

Indeed, for this reason, it is likely that many low-cost producers will delay adopting a more competitive strategy until they have made significant progress in reforming their economies. This is likely to slow the speed at which the new competitive oil market emerges. The shift to a more competitive market environment won’t just happen on its own accord, it requires a critical mass of low-cost producers to both recognise the need to adopt a more competitive strategy and, more importantly, to have reformed their economies sufficiently for them to be able to adopt such a strategy sustainably. If a majority of low-cost producers have high levels of social costs of production (and hence high fiscal break-even rates) this is likely to slow the pace at which the more competitive market environment takes hold.

Either way, the key implication is that the level of oil prices over the next 20 to 30 years is likely to depend importantly on the success that oil producers have in diversifying their economies and hence in reducing their social costs of production.

This is not meant to suggest that these countries will not respond to the shift from scarcity to abundance by reforming their economies. But history has shown that structural reform is a long and challenging process that is typically measured in decades rather than years. For that reason, as we move from an environment of perceived scarcity to abundance and oil markets become increasingly competitive, it seems likely that the average level of oil prices over the next 20 or 30 years will depend more on developments in the social cost of production across the major oil producing economies in the world than on the physical cost of extraction.

Two other points are worth highlighting from this analysis.

First, the differing levels of social costs across oil producing countries will have an important bearing on which producers are best placed to increase their market share over time. The argument that low-cost producers should use their comparative advantage to increase their market share is typically framed in terms of the physical cost of production: for example, Middle East producers gaining share relative to higher-cost producers, such as the UK or Canada.

But ultimately the ability of oil producing economies to adopt a more competitive “higher volume, lower price” strategy depends on their total cost of production, including social costs. Unless low “physical” cost producers are able to diversify their economies and provide a stable investment environment, they may lose out to less oil dependent (more-diversified) economies, even if the physical costs of production in these economies is many times greater.

Second, the emergence of US tight oil as a major new source of global oil supply does not significantly affect this analysis. It is quite possible, indeed likely, that US tight oil will increase substantially over the next 20 years. But suppose US tight oil production were to double or even quadruple, to say 10 or 20 Mb/d, that would still mean that the world’s other oil producers would probably need to provide upwards of 70 or 80 Mb/d of oil for the next 20 or 30 years. The oil price required to produce that amount of oil on a sustainable, stable basis will depend critically on the total cost of oil production in these countries, including social costs. The world cannot survive on US oil alone.

Section 5: Conclusions

Peak oil demand is all the rage.

The prospect that global oil demand will gradually slow and eventually peak has created a cottage industry of executives and commentators trying to predict the point at which demand will peak. This focus seems misplaced. The date at which oil demand will stop growing is highly uncertain and small changes in assumptions can lead to vastly different estimates. More importantly, there is little reason to believe that once it does peak, that oil demand will fall sharply. The world is likely to demand large quantities of oil for many decades to come.

Rather, the significance of peak oil is that it signals a shift in paradigm – from an age of (perceived) scarcity to an age of abundance – and with it is likely to herald a shift to a more competitive market environment. This change in paradigm is also likely to pose material challenges for oil producing economies as they try both to ensure that their oil is produced and consumed, and at the same time diversify their economies fit for a world in which they can no longer rely on oil revenues to provide their main source of revenue for the indefinite future.

The extent and pace of this diversification is likely to have an important bearing on oil prices over the next 20 or 30 years. It seems likely that many low-cost producers will delay the pace at which they adopt a more competitive “higher volume, lower price” strategy until they have made material progress in reforming their economies. More generally, it seems unlikely that oil prices will stabilise around a level in which many of the world’s major oil producing economies are running large and persistent fiscal deficits. As such, the average level of oil prices over the next few decades is likely to depend more on developments in the social cost of production across the major oil producing economies than on the physical cost of extraction.

Spencer Dale

Group chief economist, BP

Bassam Fattouh

Director of The Oxford Institute for Energy Studies

Many thanks to Catherine Ojo for excellent research assistance and to Rystad Energy for supplying the data on oil production costs.

Notes

(1) ... See for example: James Arbib and Tony Seba, ‘Rethinking Transportation 2020-2030’, A RethinkX Sector Disruption Report, May 2017; Reda Cherif, Fuad Hasanov, and Aditya Pande, ‘Riding the Energy Transition: Oil Beyond 2040’, IMF Working Paper, May 2017; Bloomberg, ‘Energy Giant Shell Says Oil Demand Could Peak in Just Five Years’, 2 November 2016; Financial Times, ‘Big energy fears peak oil demand is looming’, March 15, 2017. [Back to article]

(1) ... The need to reform and diversify their economies has long been understood by oil producing countries, but the shift in paradigm adds greater urgency to this process. [Back to article]

(1) ... BP's Energy Outlook – 2017 edition. [Back to article]

(1) ... A 3% decline rate is, if anything, a relatively conservative assumption. Major energy consultants typically assume decline rates of between 4%-6%, See, for example: IEA Energy World Outlook 2013 (p 457); Global 4.5% Oil Production Decline Rate Means No Near-Term Peak; and WoodMac forecasts stable non-OPEC decline rates through 2020. [Back to article]

(1) ... Most studies which point to a sharp fall in oil demand appear to allow for little impact from these types of rebound effects. This requires strong assumptions about either oil demand being very price inelastic, even over the longer run, or global taxes/carbon prices varying to offset any fall in wholesale prices. [Back to article]

(1) ... This critique of resource exhaustibility as a framework for analysing the oil market is not of course new – many economists have argued that available oil resources are endogenous to a variety of economic and technical factors. See, for example, Alderman, M.A. 1990, Mineral depletion, with special reference to petroleum. Review of Economics and Statistics, 72(1). [Back to article]

(1) ... BP’s Statistical Review of World Energy. [Back to article]

(1) ... BP's Energy Outlook – 2017 edition. [Back to article]

(1) ... An alternative to increasing actual oil production in the short run would be for a country to sell forward some of its future oil output. One implication of the decision by Saudi Arabia to conduct an IPO of Saudi Aramco is that it effectively capitalises a proportion of its future oil revenues. [Back to article]

(1) ... Hotelling, H. 1931. The economics of exhaustible resources. Journal of Political Economy 39 (2). [Back to article]

(1) ... IMF Regional Economic Outlook, Middle East and Central Asia, October 2017. [Back to article]

(1) ... See, for example, “Using external breakeven prices to track vulnerabilities in oil exporting countries”, Brad Sester and Cole Frank. [Back to article]