Date: 2024-12-21 Page is: DBtxt003.php txt00014574

WEF Davos 2018

World Bank Projection

The World Bank’s assessment of the global economy starts off well. But this rosy picture of the present is tempered by a stark warning about the future.

Burgess COMMENTARY

Peter Burgess

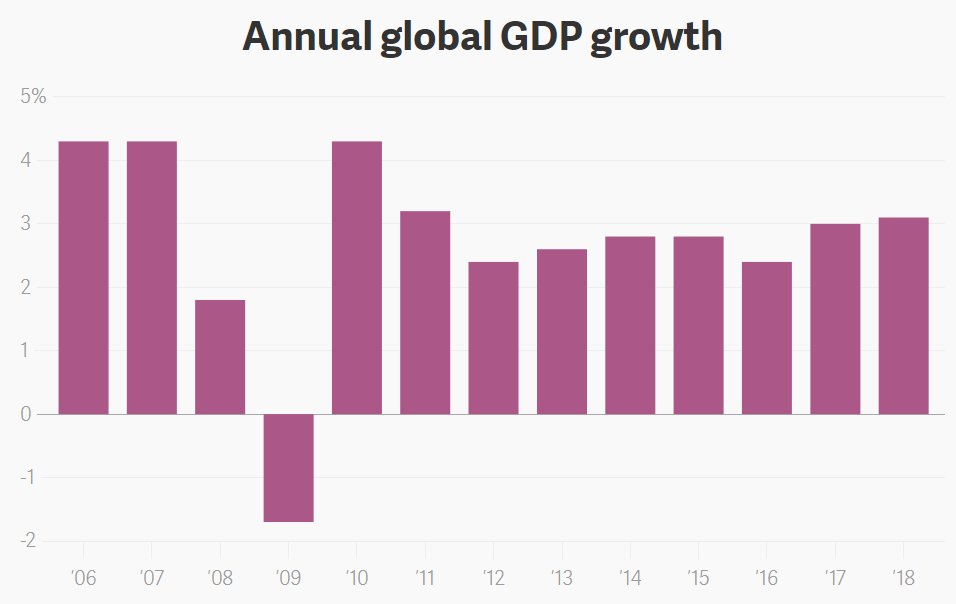

The World Bank’s assessment of the global economy starts off well. We’re in the midst of a “broad-based cyclical upturn,” which is expected to last several years. Annual global GDP growth is forecast to rise to 3.1% this year and stay at this level or just below until 2020.

And it notes that, for the first time since the 2008 financial crisis, every major region in the world is experiencing an increase in economic growth thanks to more investment, manufacturing, trade, and higher commodity prices—in other words, operating “at or near full capacity,” the organization’s report said this week.

But this rosy picture of the present is tempered by a stark warning about the future. “This is no time for complacency,” said the bank’s president, Jim Yong Kim.

There has been a slowdown in “potential growth” (a measure of how fast an economy can expand at full employment) due to years of meager productivity growth, weak investment, and changing demographics that have left many countries with ageing workforces. The World Bank says this deceleration affects economies that make up 65% of global GDP.

Between 2013 and 2017, global potential output growth was half a percentage point below its long-term average. In many countries, the output gap—the difference between the actual output and the maximum potential output of an economy—is closing or already closed. This will restrain future economic growth, the World Bank said. The slowdown in potential growth could extend into the next decade and shave a quarter of a percentage point off global GDP growth in that time.

The problem isn’t irreparable. As the slack in the global economy is diminished, the World Bank says policymakers need to make structural reforms to sustain long-term growth, such as better policies to improve education, healthcare systems, and infrastructure.

However, the organization warns that governments and “politically powerful groups” are likely to resist reform, without specifying any in particular. Calls for politicians to make reforms instead of rely on monetary policy and fiscal stimulus have been made for years by plenty of groups, including the International Monetary Fund and several central banks in advanced economies.

Overall, the risks to the World Bank’s outlook are more likely to be negative than positive, the report says. A sudden tightening of financing conditions as central banks remove stimulus, the potential for more trade protectionism, and escalating geopolitical tensions could all disrupt current economic growth. Though, like 2017, several large economies have the potential to perform better than expected.

Perhaps Donald Trump can allay some of those fears at Davos?

Read this next: The economic surprise of 2017 was Europe’s best year in a decade