Date: 2024-12-26 Page is: DBtxt003.php txt00015732

Corporate Debt

A serious hangover

A $1 Trillion Powder Keg Threatens the Corporate Bond Market // They were once models of financial strength—corporate giants like AT&T Inc., Bayer AG and British American Tobacco Plc.

Burgess COMMENTARY

Peter Burgess

A $1 Trillion Powder Keg Threatens the Corporate Bond Market

They were once models of financial strength—corporate giants like AT&T Inc., Bayer AG and British American Tobacco Plc.

Then came a decade of weak sales growth and rock-bottom interest rates, a dangerous cocktail that left many companies feeling like they had just one easy way to grow: by borrowing heaps of cash to buy competitors. The resulting acquisition binge left an unprecedented number of major corporations just a rung or two from junk credit ratings, bringing them closer to a designation that historically has made it much more expensive to fund daily business and harder to navigate economic downturns.

In fact, a lot of these companies might be rated junk already if not for leniency from credit raters. To avoid tipping over the edge now, they will have to deliver on lofty promises to cut costs and pay down borrowings quickly, before the easy money ends.

Bloomberg News delved into 50 of the biggest corporate acquisitions over the last five years, and found:

... By one key measure, more than half of the acquiring companies pushed their leverage to levels typical of junk-rated peers. But those companies, which have almost $1 trillion of debt, have been allowed to maintain investment-grade ratings by Moody’s Investors Service and S&P Global Ratings.

... The vast majority of the 50 deals—valued at $1.9 trillion collectively—were financed with debt.

... This M&A-fueled leveraging of corporate balance sheets contributed to a surge in debt rated in the bottom investment-grade tier and now represents almost half of the outstanding market, Bloomberg Barclays index data show.

“The rating agencies are giving companies too much wiggle room,” said Tom Murphy, a money manager at Columbia Threadneedle Investments. “There’s been some pretty heroic assumptions around cost savings and debt repayments laid out by some borrowers involved in mergers.”

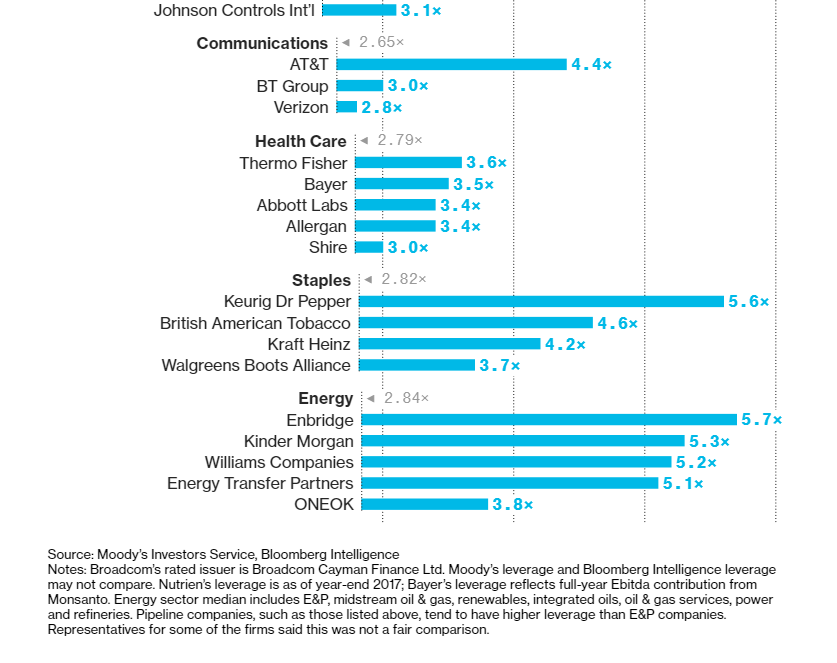

Levered Up

After a decade-long buying spree, many companies have pushed their leverage to levels that are typical of junk-rated borrowers in their sectors

Current leverage

2×

3×

4×

5×

6×

◀ 1.95× industry median leverage for BBB rated companies

Consumer Discretionary

4.4×

Newell Brands

3.5×

Marriott Int’l

Technology

◀ 1.95×

2.0×

Broadcom*

Materials

◀ 2.19×

4.5×

LafargeHolcim

3.4×

Nutrien

Industrials

◀ 2.54×

3.1×

Johnson Controls Int’l

Communications

◀ 2.65×

4.4×

AT&T

3.0×

BT Group

2.8×

Verizon

Health Care

◀ 2.79×

3.6×

Thermo Fisher

3.5×

Bayer

3.4×

Abbott Labs

3.4×

Allergan

3.0×

Shire

Staples

◀ 2.82×

5.6×

Keurig Dr Pepper

4.6×

British American Tobacco

4.2×

Kraft Heinz

3.7×

Walgreens Boots Alliance

Energy

◀ 2.84×

5.7×

Enbridge

5.3×

Kinder Morgan

5.2×

Williams Companies

5.1×

Energy Transfer Partners

3.8×

ONEOK

Source: Moody’s Investors Service, Bloomberg Intelligence

Notes: Broadcom’s rated issuer is Broadcom Cayman Finance Ltd. Moody’s leverage and Bloomberg Intelligence leverage may not compare. Nutrien’s leverage is as of year-end 2017; Bayer’s leverage reflects full-year Ebitda contribution from Monsanto. Energy sector median includes E&P, midstream oil & gas, renewables, integrated oils, oil & gas services, power and refineries. Pipeline companies, such as those listed above, tend to have higher leverage than E&P companies. Representatives for some of the firms said this was not a fair comparison.

Take Campbell Soup Co. The company borrowed more than $6 billion in the past year to buy Snyder’s-Lance Inc., the maker of pretzels and other snacks. The acquisition more than doubled the company’s debt load to nearly $10 billion, according to data compiled by Bloomberg. The company now has more than 5 times as much debt as earnings before interest, taxes, depreciation and amortization, a measure known as Ebitda, according to Moody’s.

While ratings firms evaluate a number of criteria, a company with leverage that high would be considered junk if judged on that metric alone. For example, two Campbell Soup competitors, Pinnacle Foods Inc. and Lamb Weston Holdings Inc., have lower leverage and are rated below investment-grade. But Moody’s and S&P kept Campbell at investment-grade, saying they expected the merged food company to generate enough revenue to pay down its debt quickly.

A spokesman for Campbell Soup said that it expects asset sales will allow it to cut its leverage ratio to 3 times Ebitda by 2021.

Mitigating Factors

Both Moody’s and S&P say that a company can’t be judged by its debt burden alone and that they consider a range of factors—from a company’s size and standing in its industry to the track record of its management. Both said their ratings historically have held up and that they not only assess current, but future credit risks and business conditions.

“A simple ‘point in time’ snapshot of leverage fails to account for an issuer’s expected deleveraging trajectory in the wake of an M&A deal and can present a distorted view of both an issuer’s rating and the analytical process underpinning the rating,” said Stephanie Leavitt, a spokeswoman for Moody’s.

Campbell’s plan to cut debt was cast into doubt shortly after the deal closed. In May, the soup maker’s chief executive officer unexpectedly resigned, and the company forecast earnings well below analyst expectations. Facing a potential downgrade to junk, the company said it would pay down debt by selling assets it had spent years acquiring, including its international unit and its fresh-food business.

Dr. Pepper Snapple Group Inc. stretched the bounds when it quadrupled its debt load as it combined with Keurig Green Mountain Inc. in an $18.7 billion deal in July. The merged company, Keurig Dr. Pepper Inc., was left with around $17 billion of borrowings, which Moody’s estimated would be 5.6 times the company’s Ebitda. That’s well above the median ratio of three times for a staples company in the highest junk tier.

Moody’s and S&P kept the company at investment grade, on the expectations that it would be able to nearly halve its leverage ratio within three years with its cash flow as well as by cutting costs and eliminating duplication. But cutting debt so much relative to Ebitda isn’t usually easy, said Marie Choi, a credit analyst at TCW Group Inc., which managed around $200 billion of assets as of June 30.

“It usually takes a lot longer than two to three years to go from 6 times to 2–3 times leverage,” Choi said.

A spokeswoman for Keurig Dr. Pepper said it has managed to rapidly cut leverage after past deals. After its predecessor loaded up on debt to fund a 2016 buyout by JAB Holding Co., it cut its ratio in half to 2.7 times in just two years.

The problem, says Choi, is that the credit raters are taking companies’ assumptions at face value instead of taking a more skeptical approach. In the Keurig deal, she said, Moody’s methodology placed nearly equal weighting on the company’s promises to pay down its debt as it did its ability to pay.

AT&T, Bayer

Moody’s and S&P also cut AT&T slack as it amassed the biggest corporate debt load in the world—a whopping $190 billion—to finance purchases of Time Warner and DirecTV. Bayer’s $63 billion acquisition of Monsanto in June pushed its leverage beyond that of a typical investment-grade company. And British American Tobacco was cut just two levels by Moody’s when it bought the portion of Reynolds American that it didn’t already own for $54.5 billion last year.

AT&T’s chief financial officer recently said the telecom giant will generate enough cash flow after the Time Warner acquisition to manage its obligations. A spokesman for Bayer said the company is well positioned to restore its credit rating to the A tier. A representative for British American Tobacco said that given its global presence and stable cash flow, it can take on more debt than a regional company with the same rating.

Those corporations weren’t the only ones to keep their investment-grade ratings. Companies that completed the 50 deals reviewed by Bloomberg News were downgraded by about one notch on average, but their ratings didn’t fall as much as one would expect. Their total debt-to-Ebitda ratios are still about one step higher than companies with similar ratings in the same industry, according to leverage guidelines established in June by Bloomberg Intelligence analysts Joel Levington and Noel Hebert.

Down the Spectrum

Companies’ credit ratings have dropped one level on average when funding megadeals

Rating change:

Downgraded

Upgraded

No change

Rating

BB

BB+

BBB−

BBB

BBB+

A−

A

A+

AA−

AA

AA+

AAA

Teva Pharmaceutical Industries

Dell Technologies

NXP Semiconductors

Shire

Newell Brands

Kinder Morgan

Energy Transfer Partners

Becton Dickinson and Co

Williams Companies

ONEOK

Kraft Heinz

GLP Pte

Broadcom

Allergan

Walgreens Boots Alliance

Nutrien

Marriott International

LafargeHolcim

Keurig Dr Pepper

Enbridge

DowDuPont*

BT Group

AT&T

Suntory Beverage & Food*

Thermo Fisher Scientific

Reynolds American

British American Tobacco

Bayer

Abbott Laboratories

Verizon Communications

Sempra Energy

Johnson Controls Int’l

AbbVie

Reckitt Benckiser Group

Merck KGaA, Darmstadt

Comcast

General Electric

Anheuser−Busch InBev

Medtronic

Chubb

CK Hutchison Holdings

Visa

Royal Dutch Shell

Pfizer

Berkshire Hathaway

Microsoft

Johnson & Johnson

Source: Moody’s Investors Service, S&P Global Ratings

Notes: DowDuPont’s rated issuer is Dow Chemical Co. Suntory Beverage & Food rated issuer is Suntory Holdings Ltd.

“There are deals out there that definitely look like late-cycle type of maneuvers,” said Brian Kennedy, a portfolio manager at Loomis Sayles & Co. “Whether or not the cycle continues long enough for these to be deleveraging transactions remains to be seen.”

Companies have had little reason to keep their credit ratings high during a decade of easy money, as investors worldwide shifted trillions of dollars into riskier bonds in search of higher yields. A company that was looking to borrow debt for seven years would pay just 0.5 extra percentage point in interest annually if it were rated in the BBB tier instead of the A tier, according to Bloomberg data. That amounts to just $5 million more a year for every additional $1 billion the company borrows. In October 2011, that difference would have been almost twice as high.

The result has been a surge in debt issuance in the lowest rungs of investment-grade—the biggest share of it driven by corporate acquisitions. There’s now about $2.47 trillion of U.S. corporate debt rated in the BBB tier, more than triple the level at the end of 2008. It now makes up a record 49 percent of the investment-grade bond market and has eclipsed the entire U.S. junk bond market, according to Bloomberg Barclays Index data. In 1993, for example, just 27 percent of blue-chip corporate bonds were rated at the BBB tier.

The Big Downgrade

More than half of the U.S. investment-grade index now sits in the lowest ratings tier

Rating type:

BBB

A

AA

AAA

Value

$5T

4

3

2

1

0

1998

2000

2002

2004

2006

2008

2010

2012

2014

2016

2018

Source: Bloomberg Barclays indices

The worry now is that, with so many of those BBB ratings dependent on the ability of companies to deliver on their debt-cutting promises, any hiccup in the economy or exodus of investor cash will lead to a surge of downgrades to junk. That could lift companies’ borrowing costs substantially, adding new strains to those companies. And if it were to happen en masse, it could overwhelm the $1.3 trillion U.S. speculative-grade debt market and potentially cause the weakest borrowers to lose access to capital.

In the last three economic downturns, between 7 and 15 percent of the investment-grade bond universe was downgraded to high yield, according to a report this month from Morgan Stanley. But the percentage could be higher this time around because so much of the market is rated in the BBB tier, according to the report by strategists led by Adam Richmond. When it’s all said and done, some $1.1 trillion of investment grade debt could end up as junk, they wrote.

That’s the risk, but some analysts say that mass downgrades are unlikely. For one thing, companies on the verge of junk status usually have ways to improve their credit quality, such as selling businesses, S&P wrote in a note in July.

Corporations are also generating more cash flow relative to their debt than they have historically, and that money is what ultimately pays borrowings, S&P said. By its calculations, a measure of operating cash flow is now equal to about 19 percent of debt, up from 17 percent in 2008. And while companies that acquire may seem to have high ratings relative to their debt levels, most have been good at paying down borrowings on time, and they haven’t been downgraded during this cycle any more often than other BBB companies, S&P said.

Even with those caveats, big borrowers that seem solid can end up with junk ratings. In July 2015, Teva Pharmaceutical Industries Ltd. agreed to buy the generic-drug business of Allergan Plc for about $40.5 billion, a deal that left the company with debt equal to more than 4.5 times Ebitda, a level usually associated with junk ratings.

Teva’s Fall

Moody’s didn’t lower the company to speculative-grade then. Instead, over the following months Moody’s cut the company by three notches to Baa3, noting that it expected the drugmaker to cut its debt over time using its “strong and stable cash flow.” The company’s debt levels did fall, but its earnings fell faster thanks to declines in U.S. generic drug prices and increased competition. In January of this year, Moody’s cut the company to junk. Bonds that the company issued just two years ago at around 100 cents on the dollar now trade closer to 80 cents.

When a downturn comes, assumptions that seemed reasonable before may turn out to have been overly optimistic, said Jesse Fogarty, a senior portfolio manager at Insight Investment.

“There hasn’t been a lot of delivering on this deleveraging,” Fogarty said. “At some point, these companies that have releveraged, do they have the ability to deleverage as promised? There will be some accidents where rating agencies are less willing to make that jump from investment-grade to high-yield and give them the benefit of the doubt.”

With assistance from Misyrlena Egkolfopoulou.

Edited by: Dan Wilchins and Shannon Harrington

Photo: Jeff Hutchens/Getty Images

Methodology: Bloomberg News compiled 50 of the biggest corporate acquisitions announced by investment-grade companies since the beginning of 2013 and examined their credit ratings now and before the announcements. Only completed deals were included. Financial companies were excluded, as were companies acquired by government-backed entities or those that aren't rated by Moody's and S&P. The ratings were combined into a composite number that is reflected in the graphic. It does not take ratings outlooks into account.

The companies listed in the first chart, titled “Levered Up” have two BBB-tier ratings from Moody’s and S&P. The leverage points for each company are the latest data from Moody’s, as measured by total debt to Ebitda. The median guidelines were established by Bloomberg Intelligence in June and are broken out by sector and rating, also measured as total debt to Ebitda.

Bloomberg gave each of the 47 companies identified a chance to comment on the data. Most either declined or didn’t respond. Those that did respond pointed to their efforts to pay down debt and their cash flow levels.

Kinder Morgan and Enbridge, both oil & gas pipeline companies, said that comparing their leverage to drillers isn’t appropriate because pipelines offer steadier cash flows, which supports higher debt levels. Kinder Morgan said its leverage is in line with its midstream peers.

Nutrien, a fertilizer maker formed when Potash Corp. of Saskatchewan Inc. combined with Agrium Inc., said it is shedding equity stakes as part of its merger, which should improve its net debt position in the coming months. Pharmaceutical company Merck KGaA said it follows a conservative financial policy and maintains a strong investment-grade rating.

A spokeswoman for Teva declined to comment.

Debt levels for Marriott are within the hotel operator’s targeted range as of June 30, a spokeswoman said. The company’s credit ratings are based on a number of factors, and just comparing leverage to an industry median is “very misleading”, she said.

Japan-based Suntory Beverage & Food and biotech company Shire said their respective debt repayment plans were on track. Dell Technologies, General Electric and Allergan referred to recent communications with investors in which each outlined debt reduction plans and efforts to strengthen their balance sheets.