Date: 2024-12-21 Page is: DBtxt003.php txt00016151

Geopolitics

Globalism -v- Localism

The major defect MAGA and Brexit share

Burgess COMMENTARY

I was born in 1940 and too young to have direct experience and opinions related to World War II while it was ongoing. However, during my young life and throughout my education I learned a lot about the war effort and the role of 'Empire'in helping it do be won. I could not disagree more with the conclusions that seem to have been drawn by Jonathan Fennell and indeed, a growing number of researchers who seem to be rewriting history.

Peter Burgess

The major defect MAGA and Brexit share

In June 1945, Winston Churchill, who had just overseen the British contribution to victory in the Second World War, was voted out of office in one of the most unexpected election outcomes of the twentieth century. Remarkably, the very soldiers who had enabled victory on the battlefield were central to the routing of the Conservative Party at the ballot box; they, and their social networks, voted overwhelmingly for Labour.

Churchill was a man of grand vision, of big ideas, and there was no greater mission in his life than the defeat of Nazi Germany and Imperial Japan and the retention of Britain’s special place in the world. The necessity to defeat the Axis and maintain the Empire, however, blinded him to a key dynamic: he fundamentally undervalued and misunderstood the central aspiration of his citizen soldiers in a second world war; they desired immediate and profound social change. For the ordinary citizen soldier, his participation in the war was, at heart, about building a better post-war world at home – a world with better housing, health care provision and jobs.

Churchill’s inability to fully empathize with his citizen soldiers was to have profound implications for his great mission. Churchill, and others in charge of strategy, were convinced that ordinary English, Welsh, Scots, Irish, Africans, Australians, Canadians, Indians, New Zealanders and South Africans would fight with the required determination and intensity to guarantee victory and save the Empire in its hour of need. This was the key assumption, or understanding, that drove British strategy during much of the first half of the war. It was accepted that in a newly raised citizen army men would be inadequately trained and might not be provisioned with the theoretically ideal scale or quality of materiel. But, it was expected, in this great crisis, the “great crisis of Empire,” that in spite of these drawbacks they would rise to the challenge.

As we know, they did not always meet these lofty ambitions. The defeats in France in 1940 and at Singapore and in the desert in 1942 put a nail in the Imperial coffin. In the end, Britain did not even achieve her initial reason for going to war: the restoration of a free, independent Poland. As the war dragged on, the British and Commonwealth Armies played an increasingly smaller role proportionally in fighting the Axis. On 1 September 1944, with the Normandy campaign completed, General Bernard Montgomery reverted to commanding an army group of roughly fifteen divisions. His erstwhile American subordinate, General Omar Bradley, on the other hand, rose to command close to fifty in what clearly signaled a changing of the guard. By the end of March 1945, of the 4 million uniformed men under the command of General Dwight D. Eisenhower in North-West Europe, over 2.5 million were American, with less than 900,000 British and about 180,000 Canadian. The British and Commonwealth Armies advanced across Europe into an imperial retreat.

The result was that the the post-war empire was a “pale shadow” of its former self. The cohesion of its constituent parts had been irretrievably damaged. Much of its wealth had been lost or redistributed. Nowhere was this more apparent than in the Far East. The loss of Singapore was not only a serious military defeat, but it was also a blow to British prestige. Barely two years after the war, and only five years after Churchill had uttered his famous words, that he had “not become the King’s first minister in order to preside over the liquidation of the British Empire,” Britain’s Imperial presence in India had ended. The loss of the subcontinent removed three-quarters of King George VI’s subjects overnight, reducing Britain to a second-rate power.

The history of Britain and the Commonwealth cannot, therefore, be understood outside of the context of the performance of British and Commonwealth soldiers in the Second World War. The Empire failed not only because of economic decline, or a greater desire for self-determination among its constituent peoples, but also because it failed to fully mobilize its subjects and citizens for a second great world war. Africans, Asians and even the citizens of Britain and the Dominions demonstrated, at times, an unwillingness to commit themselves fully to a cause or a polity that they believed did not adequately represent their ideals or best interests. This manifested in morale problems on the battlefield, which, in turn, influenced extremely high rates of sickness, battle exhaustion, desertion, absence without leave and surrender in key campaigns. When the human element failed, the Empire failed.

Today, the Anglo-Saxon world is enmeshed in another era of what some might term big ideas, although thankfully not in a world war. In the United Kingdom, instead of imperial unity we talk about Brexit and in the United States, President Trump’s vision for America, to make it Great Again, has captured the imagination of a significant cohort of the population. Whether one agrees with these movements or not, they are certainly radical; however, in a similar vein to Churchill’s grand vision of the 1940s, they are vulnerable to ignoring the needs of the many in preference to the visions of the few. In Britain, there is hardly a week that goes by without the announcement of a new set of figures outlining the collapse of basic public services and amenities. Violent crime is up, hospital waiting times have risen and child poverty is increasing, just to mention a few social metrics. It seems evident to many, that leaving Europe will not address the fundamental issues faced by people who voted Brexit. Trump’s presidency, the evidence suggests, will harm the welfare of those who were most likely to vote for him; tax cuts for the wealthy and building a wall along the Mexican border will not bring back a lost prosperity to middle America.

Trump and the Brexiteers might heed lessons from the Second World War. The American President, Franklin D. Roosevelt believed that the efforts demanded by the state to meet the global cataclysm that was the Second World War, required legitimacy, accorded by citizens who were invested materially and ideologically in that same state. In this sense, he linked intimately the questions of social change and social justice with the performance of American armies on the battlefield. By comparison, in his obsession with defeating the Axis, the British Prime Minister lost sight of the goals and ambitions of the ordinary man, the smallest cog in the “machinery of strategy,” but a vital one all the same. For the citizen soldier, the war was not an end in itself; it was a step on the road toward a greater aspiration, political and social reform. To succeed, big ideas had to take account of the little stories of ordinary people. If they do not, they are very likely bound to fail.

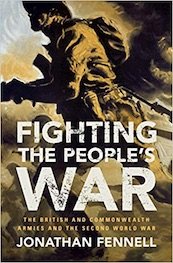

Jonathan Fennell is the author of Fighting the People’s War, the first single-volume history of the British and Commonwealth armies in WW2. His book will be published on February 7, 2019 (Cambridge University Press).