Date: 2025-01-15 Page is: DBtxt003.php txt00016683

US Politics

The Future ... About Mayor Pete Buttigieg

Mayor Pete and the Order of the Kong: How Buttigieg’s Harvard pals helped spur his rise in politics

Peter Burgess

Mayor Pete and the Order of the Kong: How Buttigieg’s Harvard pals helped spur his rise in politics

From left to right: Randall Winston, Nat Myers, Pete Buttigieg, Previn Warren, Ganesh Sitaraman, and Ryan Rippel on a pre-graduation trip to Acadia National Park in 2004.(PETE BUTTIGIEG CAMPAIGN)

A tired-looking Senator Ted Kennedy was nearing the end of a question-and-answer session with students at Harvard’s Institute of Politics when a young man in a white button-down shirt approached the microphone. It was January 2003, President George W. Bush was enjoying high approval ratings, and an ambitious college junior with his own political aspirations wanted to know whether Democrats would ever find their way out of the wilderness.

“Thank you, sir. My name’s Peter. I’m a student at the college,” said a 21-year-old Pete Buttigieg in a surprising baritone. “It feels like a lot of your colleagues have adopted a posture of being for whatever the Republicans are for, only less: The tax cuts just a smaller one, and the war, just maybe not quite as quick as the Republican war.”

As the Lion of the Senate appeared to snap to attention, Buttigieg asked whether the rest of the Democratic Party would ever “sort out what it thinks the meaning of opposition is.”

More than 15 years later, that skinny college junior with a bone to pick with the Democratic Party is putting forward his own vision for a liberal opposition as a presidential candidate — one that is deeply informed by his time in Cambridge. When Buttigieg, the mayor of South Bend, Ind., first broke through as a candidate during a CNN town hall in March, he pondered the future of American democracy and questioned the merits of the fixation among religious conservatives with sexuality in paragraph-length answers that his friends from his Harvard years recognized immediately as quintessential, undergraduate Pete.

“You listen to Pete talk now in town halls or otherwise and he’s saying the exact same things — it’s almost uncanny,” said Jason Semine, a former classmate.

Whether he’s arguing that Democrats should take back God, morality, and freedom from Republicans or that liberals too often play on conservatives’ political turf instead of articulating their own vision and values, Buttigieg’s rhetoric as a candidate sounds nearly identical to his political musings when he was at Harvard, according to interviews with more than a dozen of his former classmates.

That’s in part because Buttigieg honed these very ideas for years with a group of like-minded Harvard students he met through the Institute of Politics, or IOP, who endlessly discussed, over late-night Chinese food and beer, how the Democratic Party could make its way out of its Bush-era malaise. The group of political junkies, who became the center of his social world at Harvard and remain influential players in his candidacy today, also talked about political philosophers, novels, the Founding Fathers, and, occasionally, girl problems and their social lives.

The six young men sometimes jokingly referred to themselves as “The Order of the Kong,” after the Chinese restaurant in Harvard Square called The Hong Kong where they began meeting as freshmen over dumplings and scallion pancakes. They migrated to a back corner table of a dive bar called Charlie’s Kitchen later in college, once they were old enough to drink. Much of Buttigieg’s political outlook was shaped in these late-night back-and-forths, which ranged from Bill Clinton’s legacy to Democrats’ lackluster opposition to the Iraq war. Its members have gone on to advise a US senator and lead a government agency in California, though Buttigieg has lapped them all in pure ambition by aiming for the White House at 37, which would make him the youngest president ever if elected next year.

“I fell in with a group of friends who were mostly studying social studies and government and were generally a little more sophisticated than I was on those issues,” Buttigieg said in an interview. “I was a little more attentive to the humanities, and I think where we really connected is we were aware that there was a relationship between kind of big deep abstract ideas like we were studying in class and what was happening around us politically.”

The IOP’s forums and political discussion groups were the original catalyst for their discussions, but they continued to seek each other out privately to discuss sweeping ideas about society and progressivism that didn’t quite fit into the institute’s culture, which was more focused on tactical political questions.

“Whether or not it was spoken, all [of us were] oriented towards a life of service in some form or another,” said Ryan Rippel, a member of Buttigieg’s group who is now a director at the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation.

Although they started their discussions as teenagers, Buttigieg and his friends took themselves seriously from the very beginning. At one point, they convinced the renowned social theorist Roberto Mangabeira Unger to join them at Charlie’s, where they quizzed the elegantly dressed scholar in the dimly lit bar about the future of the American left. Two of the group’s members — Previn Warren and Ganesh Sitaraman — even published a book about the lack of youth engagement in politics while they were still undergraduates. (They give a shout-out to Buttigieg in its pages for supporting the book idea from the start.)

The group continues to deeply influence Buttigieg as a presidential candidate. Warren is now the campaign’s general counsel. And Sitaraman, a constitutional law professor and longtime adviser to Senator Elizabeth Warren, inspired one of the few original policy proposals of Buttigieg’s candidacy thus far.

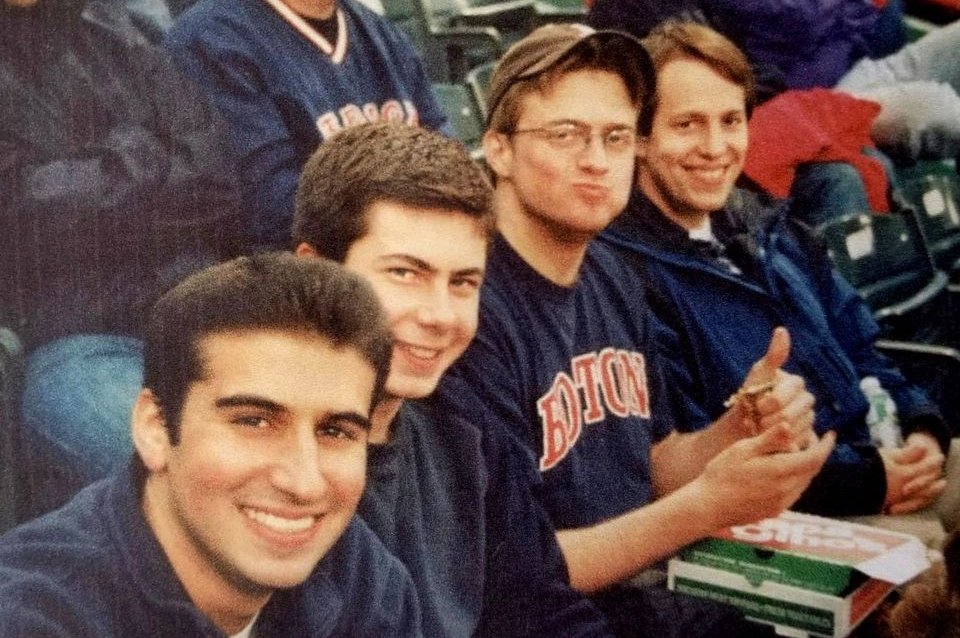

From left to right: Ilan Graff, Pete Buttigieg, Nat Myers, and Clarke Tucker at Fenway Park in 2003. (COURTESY OF CLARKE TUCKER)

At the CNN town hall in March, Buttigieg floated his friend’s idea of transforming the Supreme Court by expanding the size of the court and directing the Republican-appointed justices and the Democrat-appointed justices to unanimously pick another five justices from the lower courts to join them. Sitaraman’s idea, which he published in the Yale Law Journal, is to depoliticize the court by forcing the court’s liberal and conservative members to agree on new judges. “If we want to save that institution, I think we better be ready to tune it up as well,” Buttigieg told voters in New Hampshire.

Buttigieg said in the interview that he’s followed Sitaraman’s work closely. “In addition to being a friend from college, he’s somebody whose ideas I think are very interesting,” he said.

Back in the early 2000s, long before a CNN town hall was in the cards for any of them, the friends were consumed with the big-picture question of how Democrats could steer themselves out of the country’s decades-long centrist consensus and into a new, more muscular vision of the left. Buttigieg grappled with the topic in a series of columns for the Harvard newspaper. Just a few years later, Barack Obama would get elected in part by harnessing the progressive energy of young people like Buttigieg and his friends. But at the time, they had trouble imagining their party producing a liberal leader who could win.

“There was a real sense that Democrats weren’t framing issues in a way that spoke to our values,” said Randall Winston, another member of the club who became executive director of California’s Strategic Growth Council, an agency focused on meeting the state’s climate sustainability goals. “We as a group had an ongoing conversation about that.”

That frustration was apparent in Buttigieg’s question to Kennedy, who agreed with Buttigieg that some of his colleagues appeared too scared to run on liberal values at the time.

“They were looking for some sort of new progressive force,” recalled Harvard history professor James Kloppenberg, who joined the discussion group for a beer at Charlie’s their senior year.

Buttigieg and his friends constantly discussed how liberals could brand their issues to better appeal to voters. One of Buttigieg’s hobbyhorses was that conservatives managed to “own” moral and religious issues, according to former classmates, while the left missed out on opportunities to reframe issues such as health care and the social safety net as moral.

During his campaign, Buttigieg has created breakout moments for himself by harnessing that sort of high-toned insight, even as he’s received some blowback for lacking a fleshed-out platform of concrete policy proposals. (On Thursday, Buttigieg addressed that criticism by unveiling his first list of policy proposals on his campaign’s website.) In the CNN town hall that first attracted him widespread attention, Buttigieg criticized Vice President Mike Pence’s interpretation of Scripture as overly focusing on sexual morality while ignoring the doctrinal duties of welcoming the stranger and helping the poor.

“That’s what I get in the Gospel when I’m in church,” said Buttigieg, who grew up Roman Catholic but now attends an Episcopal church. And his campaign trail riff on how Democrats, not Republicans, are the “party of freedom” appears to draw heavily from the American philosopher John Dewey, whose works he read in Kloppenberg’s class.

That foundational circle of friends is just one part of Buttigieg’s loyal network from his Harvard days who are key to his presidential run. For someone who nearly everyone describes as an introvert born without the backslapping, gregarious politician gene, Buttigieg had a talent for making and keeping friends. In addition to Warren, who is his campaign’s general counsel, another former classmate, Stephen Brokaw, is his political director. Other Harvard friends, like fellow IOP member Joe Green, who was Facebook cofounder Mark Zuckerberg’s roommate, say they are eager to introduce him to donors in Silicon Valley and boost his candidacy any way they can.

Buttigieg, an only child of humanities professors at Notre Dame, arrived at Harvard in the fall of 2000 exhilarated by the place after a childhood in the slower pace of South Bend. He didn’t appear to have any trouble adjusting to college life, even though he wrote in his memoir, “Shortest Way Home,” that he worried about how he would “measure up” to his talented classmates. He quickly formed tight bonds with his Harvard-assigned roommates, and the seven of them decided to live together all four years.

“We’ve always felt like his brothers,” said Steve Koh, who shared bunk beds with Buttigieg freshman year. “Out of all of us, I felt like he was the one who most deeply treasured the brotherhood.”

Buttigieg named his group of roommates “the chateau” because he thought their freshman dorm looked like a castle, and he worked to create traditions to bind them together, like throwing an annual holiday party. With his politically minded friends, Buttigieg also played a key role in keeping them connected and building a mythology around their bond, a role that he continues today.

“There were certainly moments when Peter played a fatherly role to all of us,” said Rippel. “He was very mature beyond his years.”

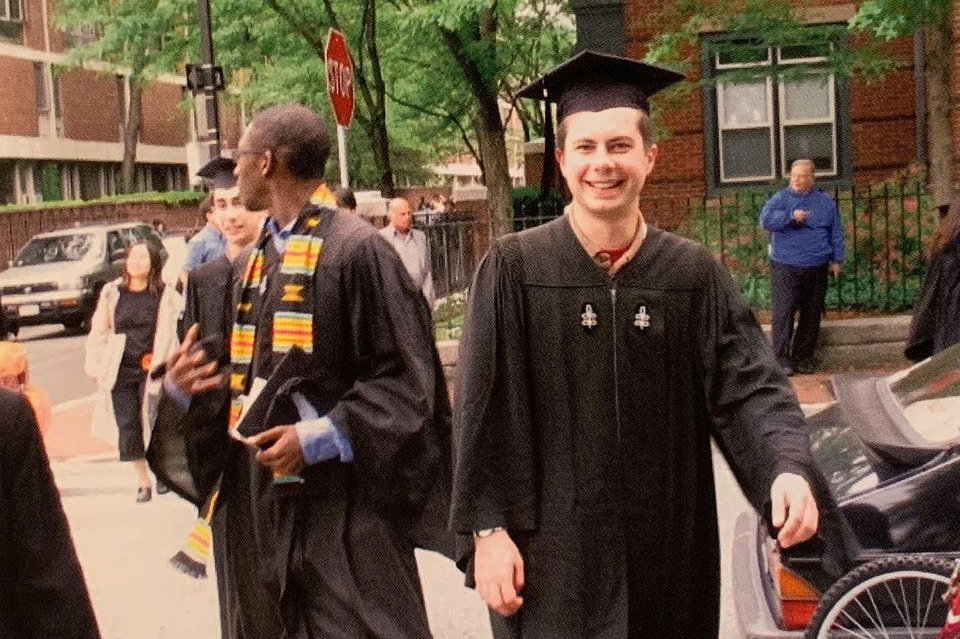

Pete Buttigieg at Harvard's Commencement in 2004.(PETE BUTTIGIEG CAMPAIGN)

Buttigieg didn’t strike many of his classmates as a mini Mr. President at the time — a breed that certainly existed on campus. Most people he knew imagined he’d run for office of some kind, but he managed not to manifest the naked ambition that landed a few of his classmates in a subtle send-up in the school newspaper for openly airing their presidential ambitions as undergraduates.

A James Joyce fan who was the most literary-minded of his friends, he majored in history and literature, not government. Buttigieg said in the Globe interview that he was uncertain about his career path while in college. “I didn’t know for sure if I’d be a journalist or an intellectual or an elected official, but I certainly thought about things like running for office and what people who run for office ought to equip themselves with in terms of language and in terms of knowledge, in terms of philosophy,” he said.

His resume told a subtly different story, one of a student who very quickly caught the campaign bug. He volunteered for Democrat Al Gore’s 2000 presidential campaign, worked at the Kennedy library, spent a summer campaigning for a Democratic House candidate in Indiana, and became president of the IOP four years after his spin as president of his high school senior class. He spent so much time at the institute’s star-studded forums and political discussions in college that his parents asked if he went to Harvard or the IOP.

By the time he was a sophomore, some friends were already pledging to help him in the future when he decided to climb up the political ladder.

“I told him my junior year, I said, ‘Peter, when you run for office, I will drop everything and help you,’ ” recalled his friend Sandhya Ramadas. “I don’t think he ever said to me at any time . . . ‘I’m going to run for office,’ but I just knew that he would.”

Even within his talented core group of political friends, Buttigieg stood out as a creature of particularly wide skills and interests. He was steadily acquiring the eight languages he now speaks, starting with Arabic his freshman year. And he also played the guitar, piano, and a didgeridoo, a long wooden pipe invented by indigenous Australians that he somehow picked up during college.

Pete Buttigieg walking along the Charles River in his college days. (PETE BUTTIGIEG CAMPAIGN)

One member of the Order of the Kong, Nat Myers, who would later be Buttigieg’s best man, recalled walking into Buttigieg’s room in Leverett House one day and seeing his friend peering at a piece of sheet music while holding a violin. Myers, stressed from the piles of schoolwork he faced, was incredulous at this conspicuous display of free time and mental energy. “He ordered an instrument on e-Bay and was teaching himself to play it. And it’s like, who does that?” Myers recalled.

He was an intimidating wunderkind, but his friends insist Buttigieg was impossible to resent, no matter how much he appeared to relish his many academic detours into musical and literary nooks and crannies while maintaining a Rhodes Scholar-level GPA and, by senior year, leading the IOP, one of the campus’s most important student groups.

“If it was anybody else, it would be so deeply obnoxious, right?” said Andy Frank, a former classmate who led the Harvard Democrats.

Buttigieg disarmed people with what seemed like a genuine curiosity about them and their lives. He was also a good listener. Known for speaking only when he really had something to say, he could surprise people when he finally dropped his thoughts on a topic.

“I always felt that if he was asking you something, he genuinely wanted to know the answer,” said Nicole Cliffe, a former classmate who dated one of Buttigieg’s roommates in college. “He’s not braggy.”

Cliffe recalled a time Buttigieg intervened when some men were harassing her at a bar, by stepping between them to defuse the situation. “He just did it very quietly and with great ease,” she said.

His college years weren’t exclusively filled with deep political discussions.

Eric Lesser, now a Massachusetts state senator who is a few years younger than Buttigieg, said the young Mayor Pete was a “normal college student like anyone else” and recalled smoking cigars with him to celebrate finishing finals. He had a sense of humor, too: Friends recalled him inserting trivia about the country of Malta, where his father was from, into every conversation possible, as a running joke about his obscure ancestry.

Buttigieg also dated at least one woman in college, and describes himself in his memoir as years away from “facing the reality” of his sexuality at the time. He didn’t come out until a decade later, when he was 33 years old and already the mayor of South Bend. His friends said it never occurred to him at the time he might be gay.

But the core of Buttigieg’s college experience, and the part that has stuck with him the most as a presidential candidate, was the ongoing discussion with his group of friends attempting to apply the political theory and history they consumed in class to the political moment. “The same questions and problems that I wrestled with then are certainly on my mind now,” Buttigieg said.

On their last day of college, right before Buttigieg would head out to work on John Kerry’s doomed 2004 presidential campaign, the nostalgic Order of the Kong decided to take one last outing as undergraduates. They piled into a van and drove the five hours to Maine’s Acadia National Park, with Buttigieg behind the wheel. They hiked all day and drove back through the night, arriving on campus by sunrise of Commencement Day. They were ending one journey and ready for the next.

“We wanted to do as much as we could in our last day as college seniors,” Rippel recalled, “and go as far as we could get.”

------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Liz Goodwin can be reached at elizabeth.goodwin@globe.com. Follow her on Twitter @lizcgoodwin

VIDEO Remarkably unremarkable: Pete Buttigieg rises in the polls as the first major openly gay candidate for president Pete Buttigieg questions Ted Kennedy in 2003

Buttigieg asked whether the rest of the Democratic Party would ever “sort out what it thinks the meaning of opposition is.”