Date: 2025-07-10 Page is: DBtxt003.php txt00017332

Corporate Purpose

More than simply profit for stockholders

Exorcising the Ghost of Milton Friedman

Peter Burgess

For someone who died more than a decade ago, Milton Friedman has been in the news a lot recently. The Business Roundtable, a collective of almost 200 CEOs of big US companies, is largely to blame.

Last month, the Roundtable issued a revised statement on the purpose of a corporation. The new statement says that corporations have a duty to serve the interests of all stakeholders: customers, employees, suppliers, communities and shareholders. This flies in the face of Friedman’s hugely influential doctrine of ‘shareholder primacy’ — the idea that the sole purpose of corporations is to maximise the amount of money they make for their shareholders.

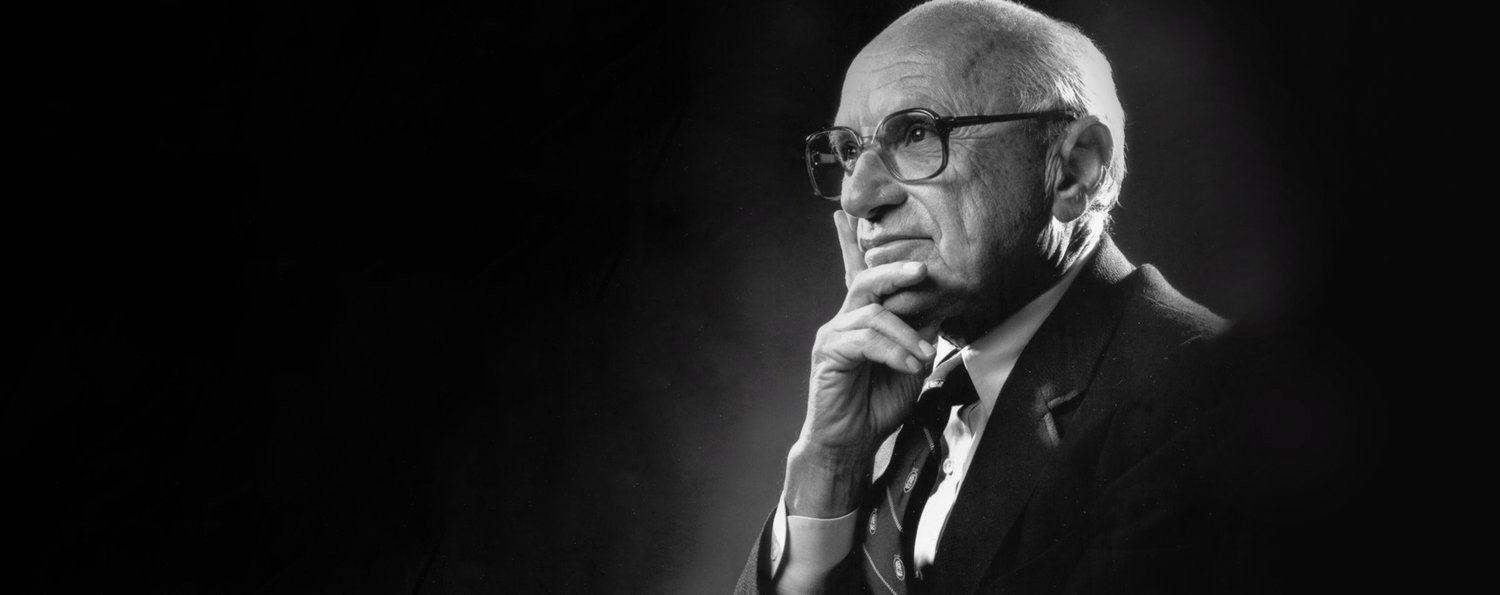

Milton Friedman, whose ideas have profoundly shaped contemporary capitalism

The Roundtable statement was criticised as dangerously radical by those who remain wedded to shareholder primacy (see, for example, the reactions of The Economist and the Council of Institutional Investors), whilst critics at the other end of the political spectrum dismissed it as self-serving PR (see Anand Giridharadas’ response on Twitter).

In between, a third group, made up of people (like me) who have long argued that stakeholder capitalism should supplant shareholder capitalism, welcomed the statement with cautious optimism and called on the Roundtable CEOs to back up their words with actions.

In a Harvard Business Review blog I wrote with my colleague John Elkington, we put forward six ways in which CEOs can prove they care about more than shareholder value.

These include taking action to narrow the gap between executive pay and median workers’ wages, giving employees an ownership stake and a seat at the boardroom table, and committing to procure goods and services locally wherever possible.

Crucially, too, we argue that committing to the logic of stakeholder capitalism means welcoming, rather than resisting, necessary legislative and regulatory interventions, such as a meaningful price on carbon emissions and the breakup of monopolies and oligopolies. (This idea of companies using their political influence for good is something I explored in a previous blog.)

It’s also something John and I cover in a recent article for the 2019 Global Goals Yearbook, in which we set out a new leadership agenda for companies, based on the initial findings of the Tomorrow’s Capitalism Inquiry.

Image Source: 2019 Global Goals Yearbook, p. 12

‘Companies’, we argue, ‘are going to have to step up to become much more active and effective agents of systems change, unless they are content simply to be passengers on a voyage captained by the ghost of Milton Friedman, which appears to be headed towards the mother of all icebergs.’

‘Whether we like it or not, companies are powerful political actors… imagine if the substantial political influence wielded by companies was targeted towards achieving market reforms that ensure social and environmental value creation is properly incentivised. This may sound far-fetched, but remember that thousands of companies already go beyond regulatory compliance in some aspect or other of their sustainability performance. In advocating for regulation that would compel their competitors to meet the same standards that they have already chosen to meet voluntarily, these companies are merely pursuing their own enlightened self-interest.’

This call to get political is just one element of the recipe we suggest for tomorrow’s corporate leaders. The table below summarises our analysis of what it takes for a company to become an effective agent of system change.

In the right-hand column, we list five functions — or roles — that every company plays: citizen, buyer, investor, employer and producer. In each case, there is a Friedmanite version of how to approach that role (eg., treating labour and raw materials as costs to be minimised), and then there is a future-fit version (eg., seeing relationships with employees and suppliers as opportunities to create social, environmental and financial value).

In the left-hand column, we list five features — or characteristics — that ultimately determine how and whether a company can commit to objectives that go beyond maximising shareholder value. Very often, we argue, there is a ‘fundamental misalignment between these different elements of a company’s DNA.’ The result, as Kate Raworth, author of Doughnut Economics, has written, is that many companies exhibit signs of “corporate schizophrenia”.

[For a more detailed explanation of each of these functions and features, see pp. 13–17 of the Global Goals Yearbook.]

Image Source: 2019 Global Goals Yearbook, p. 16

It’s easy to theorise about a post-Friedmanite world; much harder to bring it into being. Nonetheless, I remain optimistic for two reasons.

- Firstly, because none of this is pure theory. There may not yet be a single company that exhibits the future-fit version of all ten functions and features, but all of them exist somewhere already: all we have done is extrapolate from and synthesise the best, most hope-inspiring aspects of the contemporary corporate landscape.

- And secondly, because the zeitgeist — or what political scientists call the “Overton Window” — is shifting. The Business Roundtable’s new statement on corporate purpose may indeed have been conceived partly as a PR exercise — but the mere fact that 181 CEOs felt a need to issue a public statement that breaks from Friedmanite orthodoxy is an indication of the tectonic shift underway.

Volans Connecting Tomorrow's Dots Follow 41 Business Politics Economics Capitalism Opinion