Date: 2024-12-26 Page is: DBtxt003.php txt00019491

USA Politics

Surprising Success

The CARES Act ... We don’t talk enough about a bona fide bipartisan accomplishment that helped millions of Americans.

Peter Burgess

Alex Wong/Getty

Alex Wong/Getty

This is going to sound crazy, but it’s true: We don’t talk enough about a bona fide bipartisan accomplishment that helped millions of Americans. This is something that President Trump, our second-rate Flash Gordon villain, signed into law. In an election year, no less. And during a pandemic! He and a divided Congress, acting as a unified and benevolent force, lifted the most vulnerable among us from the stress and uncertainty of this crisis year—temporarily, anyway.

I’m referring, of course, to the supplemental money that the Cares Act added to unemployment compensation beginning in March, a weekly $600 sweetener to help those who were experiencing job loss as the coronavirus outbreak sent everyone into lockdown. Back in June, TNR contributor Timothy Noah called it Trump’s “greatest (indeed, sole) domestic accomplishment.” He noted that it was a “small triumph for low-income workers” and gave us a glimpse of a world where the folks at Fight for $15 had their way: That $600 per week brought many laborers’ pandemic pay above the amount they were earning before they lost their jobs—not coincidentally, to a level that would be commensurate with a $15/hour minimum wage.

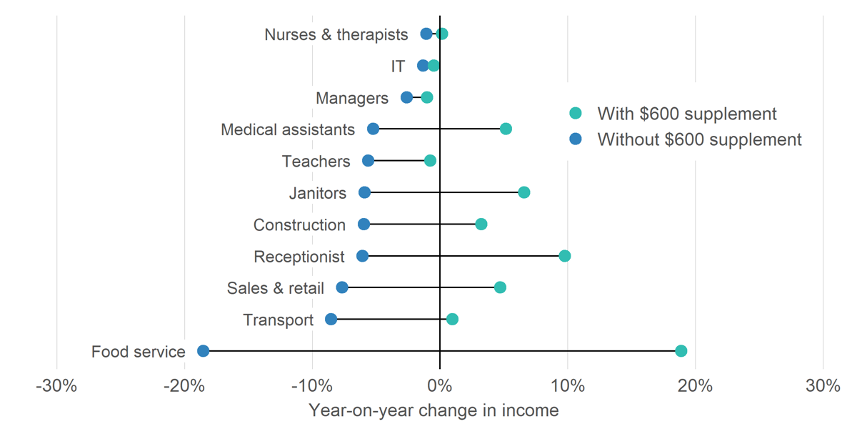

But the accolades you could have thrown at the U.I. supplement in June deserve something of a sequel. Researchers at the University of Chicago’s Harris School of Public Policy have an updated study on its impact, and the upshot is that it reversed “income patterns which would have otherwise arisen across income levels, occupations, and industries.” As University of Utah economics professor Marshall Steinbaum enthused on Twitter, noting the supplement’s effects on year-on-year change of income in certain industries, “Everyone who works in the policy world on poverty needs to look at this chart and realize that the thing that happened by chance in March did more to ameliorate poverty than anything anyone in that institutional landscape has done in their entire lives.”

This really is tremendous news. So, naturally, the $600 sweetener became a thing of the past: It expired in late July, amid (fruitless) congressional debate about another pandemic stimulus package. Trump later issued an executive order to create a temporary $400 weekly supplement, but it makes nearly impossible demands of the states. This week, as Congress resumed debate on a new package, Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell made clear what he’s willing to permit: a $300 sweetener. This would be part of a broader package that Senate Minority Leader Chuck Schumer has called “emaciated.” And it still might not pass. “I don’t know if there will be another package in the next few weeks or not,” McConnell said this week, lamenting that bipartisanship on the Hill has “descended.”

This new round of congressional dysfunction is coming at a particularly bad time. As the summer turns to autumn, the warm temperatures that fostered the relief of outdoor gatherings will fade, businesses that did a brisk patio trade will have to pack it in, flu outbreaks are likelier to add havoc and the coronavirus surge once again. Meanwhile, the economy is on unsteady terrain. As Axios reported this week, we could be headed into a “recession within a recession,” as the temporary layoffs at the beginning of the pandemic become reclassified as permanent. Those Americans who felt a small measure of relief from the $600 boost are now fully in the teeth of this crisis.

This pandemic year in America has been a nearly unending string of self-inflicted calamities. It’s almost unimaginable that just a few months ago, our embittered lawmakers came up with a game-changing anti-poverty benefit almost by accident. It’s much less surprising that, despite the clear evidence of the benefit’s success, Congress has snatched defeat from the jaws of victory. We’re not waging a war on the coronavirus; we’re waging one on ourselves.

From Atop the Soapbox

This week, Alex Pareene reveals how local police in Portsmouth, Virginia, have essentially declared war on democracy. Speaking of cops, it’s not easy to be one when you’re Black and essentially have to police the police. Matt Ford files a rather grave dispatch on the political violence being stoked by the White House and its enablers; it pairs well with Casey Michel’s long look at the “Oath Keeper” movement, which has taken up the Trumpian call to bash heads in the street. On the campaign trail, there’s a sense that Trump isn’t quite sure about the contest he’s gotten himself into: Walter Shapiro explains how the GOP’s constant fearmongering is causing no small amount of dissonance in its messaging. Matt notes that the Republicans’ character sketch of Biden is just … well, Trump. Throughout it all, cable news pundits are in full bed-wetting mode over Biden, beseeching him to pull some kind of game-changing political stunt. Osita Nwanevu has a suggestion. There was a consequential election this week in Massachusetts, where Joe Kennedy III didn’t get what he wanted and may not ever, explains Kevin Mahnken. Elsewhere, Libby Watson assesses the grim outlook for Covid-19 patients in the American health care system, Alex Shephard assays how Matt Drudge’s lack of fealty to Trump is shaking up the world of right-wing infotainment, and Eoin Higgins examines the hot new trend in Democratic politics—rehabilitating George W. Bush—and sees nothing but traps all the way down. Finally, remember how we always imagined that economic inequality could be reversed if we just find the courage to enact the right policies? Well, Tim Noah is wondering: What if we’ve been wrong about that all this time?

Copyright © 2020 The New Republic, All rights reserved.