Date: 2026-01-21 Page is: DBtxt003.php txt00020555

Economics

Paul Krugman

Krugman ... Wonking Out: Return of the monetary cockroaches ... an infestation of monetary cockroaches.

Peter Burgess

Wonking Out: Return of the monetary cockroaches

Paul Krugman

4:21 PM (15 hours ago) to me

Doomu, iStock/Getty Images

By Paul Krugman ... Opinion Columnist

Alert! Wonk warning! This is an additional email that goes deeper into the economics and some technical stuff than usual.

Some years back I tried to make a distinction between zombie ideas — ideas that should have been killed by evidence, but just keep shambling along, eating people’s brains — and cockroach ideas, false beliefs that sometimes go away for a while but always come back.

And lately I’ve been noticing an infestation of monetary cockroaches. In particular, I’m hearing a lot of buzz around how the Fed’s wanton abuse of its power to create money will soon lead to runaway inflation — or maybe that we’re already experiencing high inflation, but it’s being hidden by dishonest government statistics.

There was a lot of talk along those lines a decade ago, but it faded out as it became obvious to everyone that hyperinflation just wasn’t happening. Now it’s back, I think for a couple of reasons.

For one thing, we are seeing some actual inflation as a recovering economy runs into bottlenecks — shortages of lumber, shipping containers, used cars, etc. I believe, and the Fed believes, that these shortages are temporary, that this is only a blip and that inflation will subside; but we could be wrong, and at least there’s some substance to this concern.

But a lot of the money-printing panic is, I believe, coming from the crypto crowd. I’ve been in a number of extended (and determinedly civil) discussions with boosters of Bitcoin etc., doing my best to keep an open mind. What happens in these discussions is that skeptics like me keep pressing for an answer to the question, “What problem is cryptocurrency supposed to solve, exactly?” And at some point the answer always devolves to some version of “Fiat money is doomed because the Fed won’t stop running the printing press.”

So it seems to me that it would be useful to talk about why that’s a really bad take, and has been a bad take over and over again for the past 40 years.

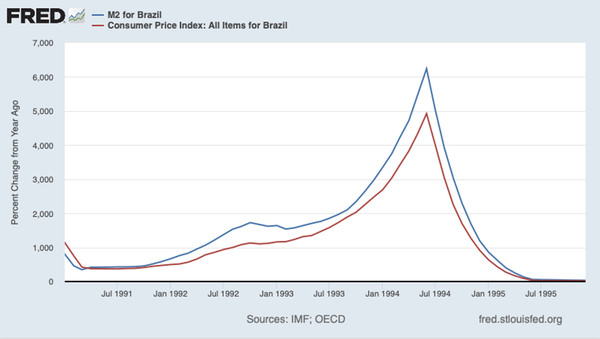

To be fair, printing huge amounts of money to pay the government’s bills does in fact lead to high inflation. Take the example of Brazil in the early 1990s:

Yes, printing money can cause inflation.FRED

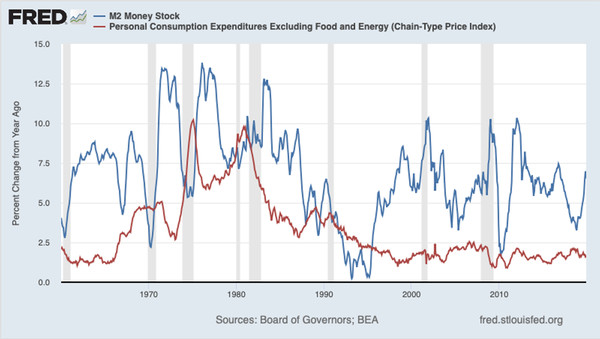

But nothing like that has happened in the U.S., even during periods when monetary aggregates like M2 have increased dramatically. Anyone claiming that big increases in M2 presage surging inflation was wrong again and again since the 1980s. I mean really, really wrong:

M2 hasn’t been much use for decades.FRED

Why?

There are actually two big fallacies in the “printing press goes brrr -> inflation” story.

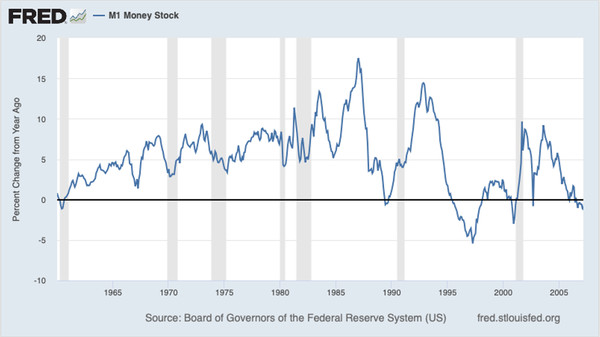

One of them is what I think of as the doctrine of immaculate inflation: the notion that an increase in the money supply somehow translates directly into inflation without causing economic overheating along the way. Many people have fallen for that fallacy over the years. Among them was no less a figure than Milton Friedman. He looked at rapid growth in M1 during the early 1980s:

Friedman’s mistake.FRED

And from 1982 to 1985 he repeatedly predicted a resurgence of inflation: 8 percent for 1983, double-digit for 1984, 8 to 10 percent for 1985.

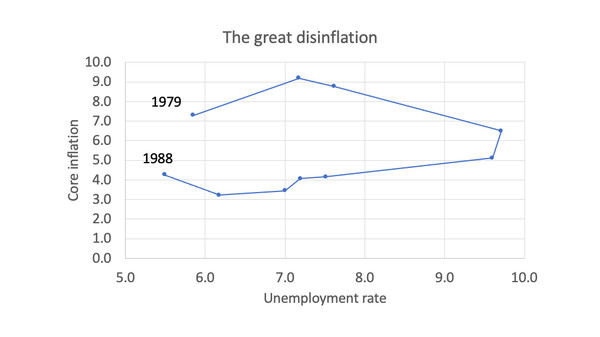

Obviously none of that happened. Instead, a slack economy with high unemployment led to declining inflation over the whole period:

Inflation, not immaculate.FRED

Today’s inflationistas, however, don’t know anything about that history.

The other fallacy of the modern inflationistas is that they don’t understand how the role of money changes in a world of very low interest rates, even though we’ve been living in that kind of world for a very long time.

Before 2007 it was expensive for people to hold money, because cash yielded no interest while bank deposits paid less than other assets like Treasury bills. So people held money only because of its liquidity — the fact that it could readily be spent. When the Fed increased the money supply, this left the public with more liquidity than it wanted, so that the money would be used to buy other assets, driving interest rates down and leading to higher overall spending.

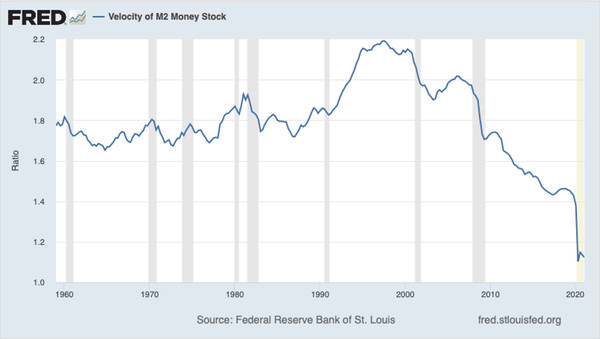

But when interest rates are very low — which they have been for years, basically because there’s a glut of savings relative to perceived investment opportunities — money is, at the margin, just another asset. When the Fed increases the money supply, people don’t feel any urgent need to put that cash to more lucrative uses, they just sit on it. The money supply goes up, but G.D.P. doesn’t, so the “velocity” of money — the ratio of G.D.P. to the money supply — plunges:

Money just sits there these days.FRED

These aren’t new insights. I wrote about all of this in the context of Japan back in the 1990s, and even that was mainly a formalization of insights many economists had held for decades. And while it took a while, my sense is that by 2014 or so the great majority of economic commentators had accepted that looking at the money supply in the U.S. context offered basically no information about future inflation.

But now we have a new crop of financial types, especially, as I said, people associated with crypto, who don’t know about any of that and, as so often happens with money people, assume that they already know everything. So we’re having a fresh infestation of monetary cockroaches, and everything has to be explained again.

Thank you for your support. Want to share The New York Times? Friends and family can enjoy unlimited digital access to our journalism with this special offer.

You received this email because you signed up for Paul Krugman from The New York Times.

The New York Times Company. 620 Eighth Avenue New York, NY 10018