Date: 2024-12-21 Page is: DBtxt003.php txt00022046

US POLITICS ... REPUBLICANS

DAVID MCCORMICK

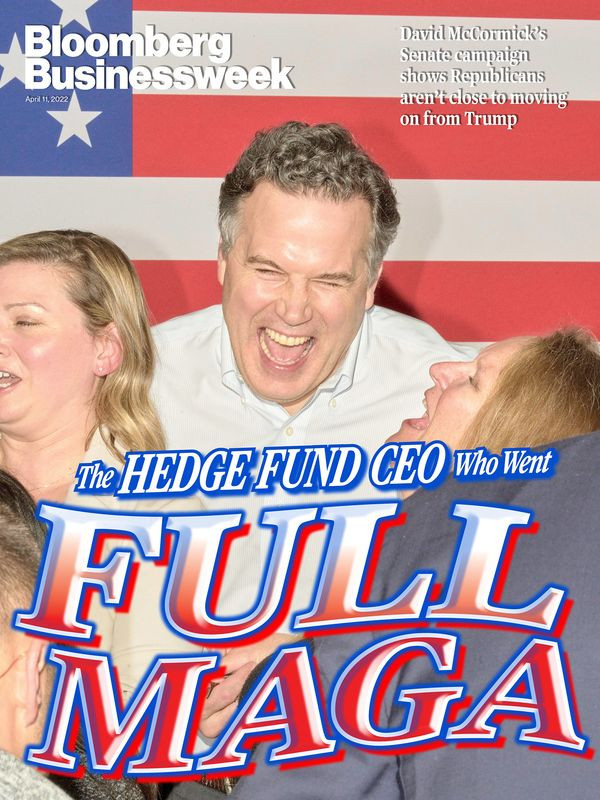

The Big Take ... The Bridgewater CEO Who Went Full MAGA ... David McCormick, who once championed diversity and inclusion under Ray Dalio, is now trying to out-Trump Dr. Oz in a Pennsylvania race that could become the most expensive Senate primary ever.

DAVID MCCORMICK

The Big Take ... The Bridgewater CEO Who Went Full MAGA ... David McCormick, who once championed diversity and inclusion under Ray Dalio, is now trying to out-Trump Dr. Oz in a Pennsylvania race that could become the most expensive Senate primary ever.

McCormick at the 2015 SALT conference in Las Vegas.Photographer: Rick Wilking/Reuters

Original article: https://www.bloomberg.com/news/features/2022-04-06/mccormick-vs-dr-oz-ex-bridgewater-ceo-gets-trumpy-in-pa-senate-race

Burgess COMMENTARY

Peter Burgess

McCormick at a rally in Pittsburgh with Sarah Huckabee Sanders on March 30. Photographer: Ross Mantle for Bloomberg Businessweek

If you were to pick the high point of David McCormick’s career in finance, it might’ve come on a bright summer day in 2019 at the Belle Haven Club, a Gatsby-esque waterside retreat in Greenwich, Conn., that’s popular with local billionaires. Among them on this occasion was McCormick’s boss, Ray Dalio, the founder of the world’s biggest hedge fund, Bridgewater Associates. Dalio had gathered the financial elites of Bridgewater and Goldman Sachs Group Inc., and brought in Harry Connick Jr. for entertainment, to celebrate McCormick’s marriage to Dina Powell, who’d recently left a top role in Donald Trump’s administration to return to Goldman. It was a moment of personal redemption for McCormick. Hired as Bridgewater’s president in 2009, he’d survived a full decade at a firm whose paranoid, contentious style is the stuff of legend. Dalio enforces a culture of “radical transparency” in which employees are encouraged to make unvarnished criticisms of one another, “so there’s no bullshit,” as Dalio puts it. He’s compared this process—favorably—to a pack of hyenas taking down a wildebeest. “This type of apparently ‘cruel’ behavior exists throughout the animal kingdom,” he wrote in a manifesto laying out his management principles. “Like death itself it is integral to the enormously complex and efficient system that has worked for as long as there has been life.” At Bridgewater, the aim of this Darwinian struggle is to foster a Spock-like intellectual rigor shorn of human emotional frailty, to better focus the firm on generating returns. Not everybody loves it. Some past employees liken Bridgewater to a cult. As a former executive elaborated to AR, a hedge fund trade magazine, “It’s isolated, it has a charismatic leader, and it has its own dogma.” Employees are known to cry in meetings. Not surprisingly, Bridgewater has a steep attrition rate. It’s been reported that about 40% of new hires from outside companies quit or are fired within a year. And the casualties can include senior executives, as McCormick almost found out. After he rose quickly to become co‑chief executive officer, the hyenas came for him. He received subpar feedback, including from Dalio, and was unceremoniously demoted. “Ray basically came in and fired me,” McCormick told Bloomberg Businessweek in a recent interview.

Featured in Bloomberg Businessweek, April 11, 2022. Photographer: Ross Mantle for Bloomberg Businessweek

But he stuck around and clawed his way back to the top. Former colleagues say that behind his easy grin and natural charisma, McCormick is a canny operator and tireless networker. One describes him as “ruthless with a smile.” (Like several other sources for this story, the former colleague requested anonymity to speak frankly without fear of retribution.) The demotion didn’t stop McCormick from cultivating Dalio. A co-captain of the West Point wrestling team who served as a paratrooper in the first Gulf War, McCormick took his boss on excursions such as a daylong private visit with a U.S. Army Ranger patrol in the Florida Everglades, which included hand-to-hand combat training. The rugged bonding rituals appeared to resonate with Dalio, who likes to describe Bridgewater employees as “intellectual Navy SEALs.” One Bridgewater colleague says McCormick began referring to himself as “the Ray whisperer,” and the characterization fit. “Ray is a pretty socially awkward guy. David is not,” the former colleague says. “It was a pretty important thing for Ray.” It was for McCormick, too. In 2017 he reclaimed the co-CEO position. Two years later, Dalio promoted him again, to full CEO. The party at the Belle Haven was the capstone to McCormick’s resurrection, culminating with a public display of Dalio’s fondness for him. According to several of the guests, Dalio rose, pulled out his iPhone, and awkwardly read a sincere and moving toast to McCormick and his bride—one that went well beyond mere professional courtesy. One Goldman banker says it was as if Dalio were toasting his own son. At that point, McCormick had nothing left to prove. But even as Dalio was feting him, he was lining up his next move. Few people who’d been at the Belle Haven Club were surprised when, this January, McCormick left Bridgewater and jumped into the Republican primary for Pennsylvania’s open Senate seat—one of the country’s most important races this fall, with control of the chamber likely hanging in the balance. It was an open secret among his colleagues that he’d long harbored political ambitions, and that these may not end at the U.S. Capitol. For a certain type of Wall Street-friendly, establishment Republican—the type who frequent Belle Haven—McCormick might register as the ideal corrective to the disorder and chaos of Donald Trump, a man many financial elites laughed at behind his back even as his presidency vastly enriched them. With his military and business background, advanced degrees, personal charisma, and wealth, McCormick has the résumé to guide the GOP into a saner, post-Trump era. Instead he went in an entirely different direction. To the astonishment of the Bridgewater crowd, he shed his smooth, Davos Man persona and transformed himself faster than Clark Kent in a phone booth into a Trump-touting, China-bashing MAGA acolyte. In the first weeks of his candidacy, McCormick traveled to the U.S.-Mexico border to decry “illegal immigrants … coming in record number.” He aired a campaign ad during the Super Bowl in which a crowd chants “Let’s Go Brandon!”—MAGA code for “F--- Joe Biden!” He also hired a team of marquee Trump veterans, including Stephen Miller and Hope Hicks, and began tweeting out articles from Breitbart.com, the right-wing website infamous for such headlines as “Birth Control Makes Women Unattractive and Crazy” and “Hoist It High and Proud: The Confederate Flag Proclaims a Glorious Heritage.” McCormick’s former co-workers circulate his ads, horrified, puzzled, or amused at their old boss’s transformation. “Is Connecticut Dave McCormick the real one, or is Pennsylvania Dave McCormick the real one?” one asks. “Or is the real Dave McCormick a chameleon who’ll be whatever he needs to be to succeed?” To succeed in the GOP right now, any party activist will attest, the most important thing is to be seen as unfailingly loyal to Trump. And just as McCormick did what he had to do to navigate Bridgewater and win back Dalio, he’s signaled he’ll do whatever is necessary to win over—or at least not anger—another mercurial kingmaker with a cult following. Most people who know Trump think he’ll be the tougher target to win over and keep onside. Even slavishly loyal devotees have discovered they can instantly fall out of Trump’s good graces. (Ask Mike Pence.) As alien as McCormick may appear to some of his old colleagues, he’s a familiar Washington type. “I get two, three calls a week from rich guys thinking about running for president or senator,” says Steve Bannon, who helped put one in the White House. The kind of people who attempt to leverage business success to reach high political office tend to have a common set of characteristics: They’re hyperambitious, ideologically flexible, and convinced that their skill set will transfer easily to politics. Most are swiftly disabused of this notion. But so far, McCormick is succeeding in what’s shaping up to be one of the strangest and most expensive Senate primaries in U.S. history. His chief competitors thus far are cardiothoracic surgeon and TV personality Dr. Mehmet Oz and Carla Sands, a wealthy widow who served as Trump’s ambassador to Denmark. All are jockeying for Trump’s favor and pushing what McCormick for his part calls an “America First agenda.” With the primary slated for May 17, a recent Fox News poll found McCormick beating Oz 24% to 15%, with Sands and two other candidates in single digits. Whether or not McCormick’s success persists, it has already revealed something important about Republican politics, and about the business world’s relationship to Trump. Ever since the violent Jan. 6 insurrection, a group of Republicans, led by Senate Minority Leader Mitch McConnell, has pushed the idea that Trump’s influence has diminished and that the GOP is moving in a new direction. Pennsylvania’s primary proves otherwise: Everyone’s clamoring for the former president’s seal of approval. “If President Trump endorsed me, I’d be delighted,” McCormick says. He recently won a minor coup by securing the backing of Sean Parnell, whom Trump originally endorsed in the race, but who dropped out last November after his estranged wife accused him of spousal and child abuse. Parnell denies the allegations. Wall Street, too, seems to have concluded that Trump, or at least Trumpism, isn’t going away. Five years ago another major hedge fund CEO, Robert Mercer, was drummed out of Renaissance Technologies for holding a private stake in Breitbart News Network LLC, because the association was deemed toxic. But McCormick’s most steadfast supporters in the finance community haven’t flinched at his appearances on Breitbart podcasts. “Everyone thinks he’s a very smart, very pragmatic guy,” says Gary Cohn, the former Goldman Sachs chief operating officer, who became Trump’s top economic adviser. “The finance world understands that you’ve got to get elected.” Of course, Trump himself has yet to weigh in. How he feels about McCormick and Oz, and what he might do, is a topic of intense interest in Republican circles. A lot is riding on how McCormick performs, and on who he reveals himself to be, over the next few weeks.

A camo McCormick cap in Columbia, Pa., in February.Photographer: Blaine Shahan/LNP Media Group

In person, McCormick is the furthest thing from a fire-breathing Trump partisan. His pitch to voters is low-key and self-deprecating. “Show of hands,” he says to a lunchtime crowd at the Valley Family Restaurant in Bethlehem. “How many people have applied for a job where you make a lot less money and you know your reputation is going to be diminished?” Anyone expecting a pushy hedge fund jerk is quickly disarmed. McCormick strains to put a modest, local gloss on a high-wattage career that’s carried him far beyond his birthplace near Pittsburgh. After graduating from West Point and serving in the first Gulf War, he earned a doctorate in international affairs from Princeton. Then he worked for McKinsey & Co. and George W. Bush’s Treasury Department before Dalio lured him to Bridgewater’s headquarters in Westport, Conn. McCormick alludes to that last stop only vaguely, carefully referring to himself as “a businessman” who worked for “an investment firm” rather than as the former CEO of a $150 billion hedge fund. Nor does he mention his reputed nine-figure net worth. “David’s trying to shed the veneer of ‘hedge fund manager,’ ” says former Pennsylvania Senator Rick Santorum. Trump’s example notwithstanding, extreme wealth remains a charged political subject in blue-collar America, especially when it has a Wall Street provenance. “He’s a rich guy from Connecticut masquerading as a regular guy from Pennsylvania,” says Stuart Stevens, who saw blowback from similar dynamics when he managed Mitt Romney’s 2012 presidential campaign. But McCormick does a passable job of putting out “regular guy” vibes, going table to table to introduce himself, shake every hand, and connect. In small settings he’s a natural, almost Clintonian, politician. One midlevel Bridgewater executive, who had regular dealings with McCormick though didn’t work for him directly, says he’s got the ability: “If he has a superpower, it is listening very, very deeply, ingesting what you’ve said, and then combining it with his past experience and his general logic and thoughtfulness, and playing it back while making lateral connections between the thing that you said and other things that he knows are going on that may not be obvious.” It’s no mystery why McCormick hasn’t parlayed his talents to try to push the Republican Party beyond Trump. A GOP consultant in Pennsylvania who isn’t working for a Senate candidate shared with Businessweek the results of a recent private poll of the state’s Republican primary voters: 82% have a favorable view of Trump, and 70% believe the 2020 election was stolen from him. “I feel like I answer things directly and honestly, you know? I feel like I’m giving authentic answers. Which may, in the end, get me in trouble” Despite McCormick’s best efforts, it’s plain that he speaks MAGA only as a second language. The America First agenda he lays out to crowds at restaurants and diners involves restoring Trump’s “pro-growth economic policies and deregulation,” “finishing Trump’s border wall,” and stepping up drilling and fracking (a big deal in Pennsylvania) to free the U.S. from foreign energy dependence. But while McCormick has grasped the language, he doesn’t muster the anger and resentment that other Republicans bring to the Trump agenda. Two decades in corporate boardrooms have left him ill-equipped to play the role of aggrieved culture warrior. The CEO who launched Bridgewater’s “Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion” initiative—who was himself, just last fall, recognized by a women’s group as a “global champion of inclusion”—sounds less than convincing decrying the pernicious effects of “woke liberalism.” To remain viable, McCormick must constantly demonstrate his allegiance to Trump. But Pennsylvania’s quirky electoral system has attracted other wealthy candidates to the Senate race, and they’re pounding McCormick with millions of dollars of negative ads trying to discredit his MAGA authenticity. (Rich outsiders can’t target the governor’s seat in Pennsylvania, because the state requires candidates to have lived there for at least seven years; U.S. Senate candidates need only be residents by Election Day.) Members of this “carpetbagger coalition,” as Santorum jokingly calls them, have used their substantial war chests to attack one another, in the process eclipsing candidates of lesser means. According to the ad-tracking company AdImpact, candidates and outside groups have already spent more than $43 million in the GOP Senate primary, vs. just $10 million in the gubernatorial primary, putting it on pace to become the most expensive ever. The ads attacking McCormick have been directed largely at his work for Bridgewater, and particularly at the firm’s close ties to China—the Oz campaign has branded him “Beijing Dave.” Bridgewater has managed Chinese state money for nearly two decades, including from the country’s sovereign wealth fund and the State Administration of Foreign Exchange. Those two entities account for about $5 billion, enough to make China one of Bridgewater’s biggest clients by assets, according to people familiar with the firm. And as Katherine Burton of Bloomberg News has reported, Dalio and Bridgewater have hosted Chinese Communist Party officials at the firm’s Connecticut headquarters. Last November, while McCormick was still CEO, the firm raised an additional $1.3 billion for a new private fund in China, making Bridgewater the biggest foreign hedge fund manager operating there. On the campaign trail, McCormick takes pains to downplay these investments, emphasizing that China accounts for only 2% of Bridgewater’s revenue. But local Republican officials say the vulnerability is real. “There’s questions about his China background,” says Craig DeFranco, a committeeman from Northampton County who’s come to see McCormick at the Valley Family Restaurant and is neutral in the race. “It’s an especially big thing right now with how they’re cozying up to Russia.” Sliding into a booth at a diner in Nazareth later on, McCormick professes not to be fazed by the attacks. “If you’re going to get in the ring at this level, in this race—this is like going straight to the NFL,” he says. He jokes that the thick skin he developed at Bridgewater is proving useful in politics. On the subject of Bridgewater and China, however, he’s programmed for caution. Dalio, he says, is someone “I have a lot of admiration for, a lot of gratitude for the opportunity he gave me.” But, he hastens to add, “we had a lot of disagreements on how to run the company, in some cases—disagreements on China and other things.” He won’t elaborate on what exactly those disagreements were, or even on how the firm invests its Chinese money. “Because I’m no longer at Bridgewater,” McCormick says, “I’m not going to get into this with you.” He will say that his time at the company was a net positive. And he remains a proud adherent of Dalio’s brutally open culture. “One thing that’s great about Bridgewater is that you’re encouraged to speak with complete and utter candor,” he says. “I feel like—and you’ll be the judge of this—I feel like I answer things directly and honestly, you know? I feel like I’m giving authentic answers. Which may, in the end, get me in trouble.”

McCormick at a forum in Shanghai in 2008, while he was with the U.S. Treasury Department.Photo: Imaginechina/AP Photo

That McCormick hasn’t, to date, encountered all that much trouble over his Bridgewater tenure has been a matter of some frustration for his chief adversary in the race: Oz. Standing in the men’s room before a town hall event in Blue Bell, Oz tells a Businessweek reporter he’s incredulous that McCormick isn’t paying a higher political price for Bridgewater’s track record—and not just on China. “Why is nobody reporting on how he ripped off the teachers’ pension fund when he was at Bridgewater?” he demands to know. “They had returns under 2% while he was CEO!” Oz is referring to Pennsylvania’s Public School Employees’ Retirement System, a state pension fund that at its peak in 2020 had more than $4 billion invested with Bridgewater, more than with any other firm. Bridgewater put the bulk of the PSERS money in an alternative “risk parity” fund that was designed to withstand market disruptions but didn’t. The fund tanked when the coronavirus hit, badly trailing the S&P 500 and producing such lousy returns that it forced some teachers to increase their pension contributions. Public filings show that PSERS paid Bridgewater more than $47 million in fees in 2020 and 2021, while McCormick was CEO. “The returns were so poor!” Oz fumes as he vigorously washes his hands. “I can get Treasury composite returns better than that! What’s fascinating to me—the returns were so low that they’re taxing every schoolteacher in Pennsylvania $200 a year, and every taxpayer has to put money into the pension fund.” (Fact check: every teacher hired after 2011.) Oz is conflicted about whether to go on the attack. “You know, I’m concerned it’s a little complicated for the average person. But if you’re getting paid three-quarters of a billion dollars”—he seems to be alluding to the $560 million in fees that public records show PSERS paid Bridgewater from 2001 to 2021—“and folks aren’t making any money, there needs to be some course correction.” Oz says teachers are approaching him asking, “Why am I paying extra money?” As he dries his hands, Oz, who has a business degree from the Wharton School in addition to his medical degrees, ponders the injustice. “I’m surprised they don’t have a clawback provision for that,” he says. Most frustrating to him from a campaign standpoint, he confesses, is that the pension debacle actually has led to quite a bit of coverage critical of Bridgewater. He’s particularly impressed by the work of the Philadelphia Inquirer’s “Spotlight” team. But he says it’s missed one big thing: McCormick’s role in the disaster. “They haven’t talked about him,” Oz grouses. “I’m, like, stunned! I don’t think they’ve connected that he was the CEO of Bridgewater!” (A few weeks later, the Inquirer did publish a story highlighting the connection. Bridgewater declined to comment to Businessweek. A McCormick spokeswoman said in a statement that the firm’s “conservative approach reflected the risk PSERS wanted to take for its retirees and delivered results in line with expectations.”) When Oz comes bounding out to greet the audience a few minutes later, he sticks to familiar culture-war themes, blasting vaccine mandates and Dr. Anthony Fauci and complaining that the media is trying to cancel him. Talk of PSERS doesn’t leave the men’s room. The performance feels tailored to appeal to one man in particular. Oz, it should be said, is a more convincing vessel of Trumpian grievance than McCormick—wild, frenetic, slightly unhinged, and always attentive to the campaign cameraman, who mirrors his every move like a duet partner.

Trump and McCormick at Trump National Golf Club in Bedminster, N.J., in 2016.Photographer: Mike Segar/Reuters

The race within the primary race is the competition between McCormick and Oz to win Trump’s blessing, or at least to avoid his disfavor. McCormick, with Miller and Hicks already on board, has also locked up the support of Trump White House veterans Kellyanne Conway and Sarah Huckabee Sanders, in addition to being married to Powell, one of few who left Trump’s employ on good terms. But Oz has secured powerful allies of his own, including Sean Hannity, who provides him a regular platform on Fox News that he can use to reach Trump, as well as Melania Trump, who NBC News reported supports Oz and has shared her views with her husband. “There are a lot of Melanias out there,” an unnamed Trump insider declared to NBC, “a lot of women in whose living room and bedroom TVs Dr. Oz has been for a decade.” With the race entering its final weeks, the challenge before McCormick will be to woo Trump without torching his electability come fall. McCormick’s supporters believe he can do it, citing the example of Glenn Youngkin—another wealthy finance executive—who was elected governor of Virginia last year. But Youngkin became the Republican candidate after being chosen by caucus, rather than in a contested primary, meaning he never had to face a fusillade of negative ads and character attacks like the one coming at McCormick. Youngkin mostly dodged the tough questions that increasingly drive a fault line through the Republican Party and alienate independents and Democrats. The toughest question of all, and the one that illuminates where the true power lies in today’s GOP, is whether a candidate believes, and will state publicly, that Trump was the rightful winner of the 2020 election and had it stolen from him by fraudulent means. Even downplaying the issue can invite Trump’s wrath. On March 22 he angrily revoked his endorsement of Representative Mo Brooks in Mississippi’s Republican Senate primary after Brooks batted away an inquiry about election theft by suggesting that his questioner “put that behind you.” In a caustic statement, Trump said Brooks “made a horrible mistake recently when he went ‘woke’ … despite the fact that the Election was rife with fraud and irregularities.” He added a warning that doubled as a threat: “If we forget, the Radical Left Democrats will continue to Cheat and Steal Elections … the 2020 Election was rigged and we can’t let them get away with it.” The demand that candidates accept such an obvious lie seems antithetical to the Bridgewater culture of radical truth-telling that McCormick still touts. But then, he’s no longer trying to convince a conference room full of investment managers. Speaking before the Republican lunch crowd in Nazareth, McCormick elides the matter by saying that Pennsylvanians’ doubts about the integrity of the election warrant strict new voter ID laws. But he doesn’t share his personal view on the 2020 election. Back in the diner booth, the question is put to him directly: Was it stolen? McCormick starts to answer a different question. “I think that within Pennsylvania, certainly there were lots of doubts—” But the question is about the national race. Does he agree with Trump that it was stolen? “I think on the national level, maybe to just take that, we have all sorts of indications of electoral—let me talk about Pennsylvania as an example of the broader thing we have, which is we’ve got all sorts of election irregularities which have essentially created a situation where Republicans, the majority of Republicans, don’t believe in the results—” Yes, but the question is about you specifically, he’s reminded. Do you think the election was stolen? “I’m going to answer the question I want to answer. So I think that’s a huge problem. As someone who’s defended, someone who’s fought for our country, if that’s a huge problem in our republic then we’ve got to have electoral reform that addresses that, that has to happen at the state level. I said yesterday, I’ll say it again: Voter ID is a key part of that. And that’s what we’ve got to be thinking about for 2022 and 2024.” He still hasn’t answered the question. When it’s put to him one last time, McCormick glances at the recorder on the table in front of him and looks pained. He never does give an answer. But his next words are as transparent as anything uttered in a Bridgewater conference room. “I think we’ll call it a wrap,” he says. Read next: Trump’s Favorite Postmaster Is Surviving Biden—and Maybe Even Saving the USPS