OVERVIEW

MANAGEMENT

PERFORMANCE

POSSIBILITIES

CAPITALS

ACTIVITIES

ACTORS

BURGESS

| |||||||||

| HOME | SN-BRIEFS |

SYSTEM OVERVIEW |

EFFECTIVE MANAGEMENT |

PROGRESS PERFORMANCE |

PROBLEMS POSSIBILITIES |

STATE CAPITALS |

FLOW ACTIVITIES |

FLOW ACTORS |

PETER BURGESS |

| SiteNav | SitNav (0) | SitNav (1) | SitNav (2) | SitNav (3) | SitNav (4) | SitNav (5) | SitNav (6) | SitNav (7) | SitNav (8) |

| Date: 2025-04-05 Page is: DBtxt001.php txt00022503 | |||||||||

|

THE UKRAINE WAR

THE DIGITAL FRONT WIRED ... Ukraine’s Digital Ministry Is a Formidable War Machine

Wide shot of people in an auditorium during a speaking event with portraits of the Ministry of Digital Transformation ... COURTESY OF MINISTRY OF DIGITAL TRANSFORMATION Original article: https://www.wired.com/story/ukraine-digital-ministry-war/ Peter Burgess COMMENTARY Why am I not surprised by this article? I have been quietly aware of the advanced software capabilies of both Russian and Ukrainian youth for several years, and especially the Ukrainians. There has been a lot of talk about Russian 'hacking' and their social media offensives, but less about the countermeasures that have been developed in Ukraine and the Eastern flank of NATO to keep themselves safe ... safer ... from Russian attack. During the last 100 days, Ukraine has mobilized to good effect. It is pretty impressive and immensely important. Peter Burgess |

|

Ukraine’s Digital Ministry Is a Formidable War Machine

A government department run by savvy tech “freaks” has become a surprise defense against Russia. Written by TOM SIMONITE and GIAN M. VOLPICELLI ... WIRED BUSINESS MAR 17, 2022 7:00 AM VALERIYA IONAN, A deputy minister at Ukraine’s Ministry for Digital Transformation, was breastfeeding her two-month-old son Mars when the first explosions boomed over Kyiv in the early hours of February 24. “I didn’t get at first what was happening,” she says. Cold truth soon dawned: Russia was invading Ukraine. Ionan, a 31-year-old MBA who previously worked in marketing, hastily set up a call with other leaders at Ukraine’s digital ministry. The department, staffed by tech-savvy millennials and led by Mykhailo Fedorov, a 31-year-old founder of a digital marketing startup, was established to digitize government services and boost Ukraine’s tech industry. Now it had to figure out what digital bureaucrats can offer in wartime.

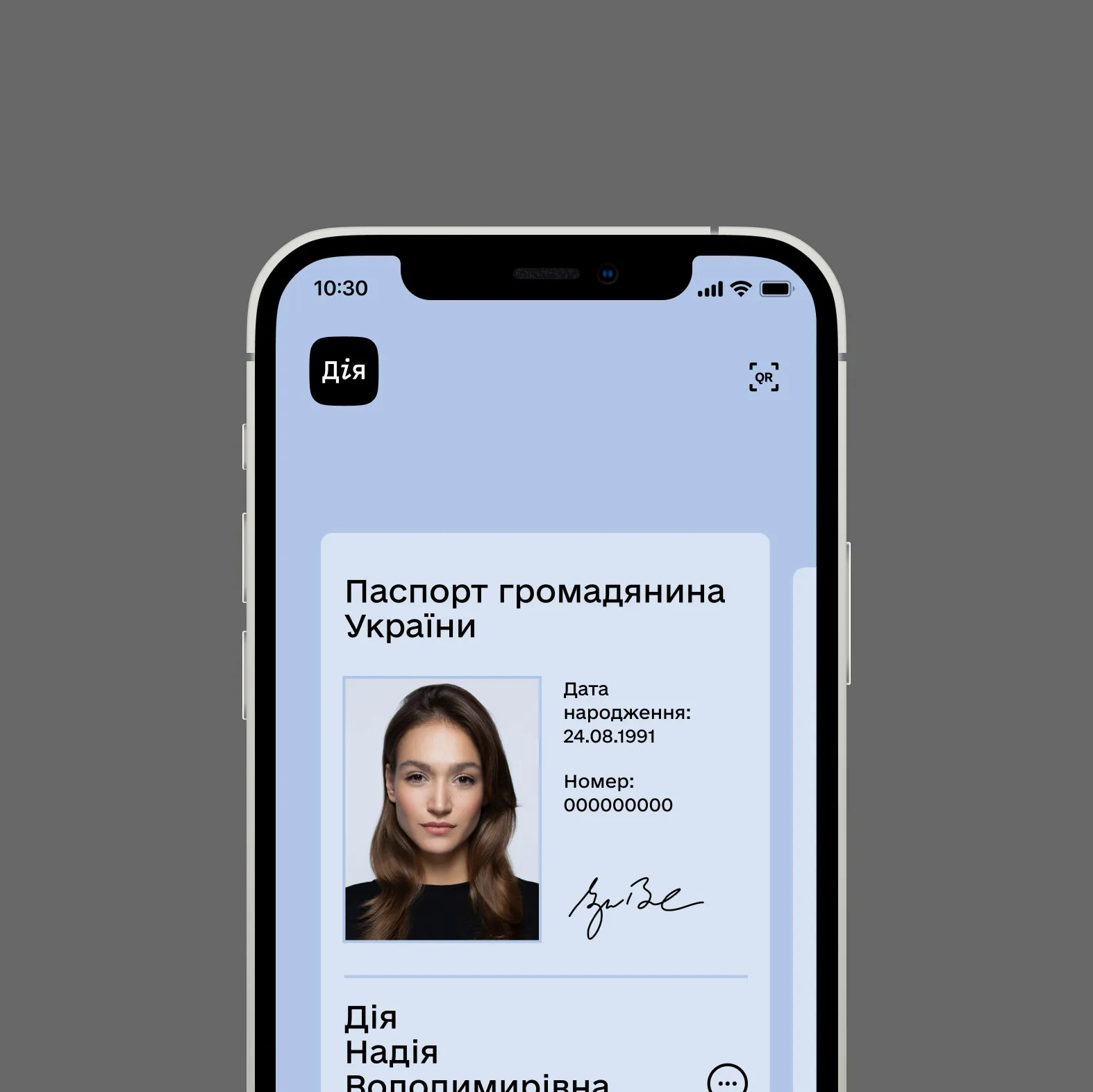

Portrait of Mykhailo Fedorov the Vice Prime Minister of the Ministry of Digital Transformation in Ukraine ... COURTESY OF MINISTRY OF DIGITAL TRANSFORMATION The projects the ministry came up with have made it a linchpin of Ukraine’s fight against Russia—and the country’s broad support among world leaders and tech CEOs. Within three days of the first missiles falling on Kyiv, Federov and his staff launched a public campaign to pressure US tech giants to cut off Russia, began accepting cryptocurrency donations to support Ukraine’s military, secured access to Elon Musk’s Starlink satellite internet service, and began recruiting a volunteer “IT Army” to hack Russian targets. More recent projects include a chatbot for citizens to submit images or videos of Russian troop movements. “We have restructured the Ministry of Digital Transformation into a clear military organization,” says Anton Melnyk, an adviser to the department. Most companies publicly targeted by Fedorov, including Apple, Google, and Facebook’s parent company Meta, have now shut down operations in Russia, restricted Russian government accounts, or halted sales in the country. Apple, Google, and Facebook did not respond to requests to comment. Crypto donations to Ukraine reached about $100 million last week, and Musk has shipped two batches of satellite internet receivers to patch connectivity gaps. The successes of the ministry’s pivot still leave one larger question unanswered—as Russia’s forces keep advancing, will these clever digital defense projects matter? Comedian turned politician Volodymyr Zelensky handed Fedorov the newly-created Ministry for Digital Transformation in August 2019, shortly after the entrepreneur helped him win the presidential election with a slick digital campaign. Fedorov was charged with delivering on a vision for easy-to-use online government services Zelensky called “the state in a smartphone.” “He [Fedorov] was this young technocrat, from the business side of the digital sector, and a lot of people were really skeptical,” Tanya Lokot, an associate professor in Digital Media and Society at Dublin City University. “Many of the young officials Zelensky appointed didn't have much experience of actual governance, or of being in government.” Fedorov declined an interview request. Fedorov, who also serves as Ukraine’s deputy prime minister, tapped the country’s thriving tech scene to staff his ministry. By hiring founders, marketers, social media experts, and computer programmers, he created a department unlike any other in Ukraine’s government. “There were no old people, and lots of businesspeople,” says Max Semenchuk, a blockchain entrepreneur who works as an adviser to the ministry. The ministry’s staff, who sometimes wore matching hoodies as they worked in the government’s western Kyiv offices, came to think of themselves as a formidable unit of “freaks” inside the government machine, says Mstyslav Banik, the ministry’s head of e-services development, who has known Fedorov since they both worked in digital marketing. In a startup or big corporation their obsession with speed and leveraging the internet would seem unsurprising; inside the government bureaucracy it was a revolution. Until the war, the ministry’s most prominent project was an app called Diia intended to deliver the “state in a smartphone” concept. It can function as an electronic passport or driver license and also provides other services, such as easy payment of traffic fines. The project sped from proposal to release, in February 2020, in just over four months and is currently used by around 14 million Ukrainians. Before the war, Fedorov checked in on the Diia project three times a week through scheduled Zoom calls that began at 7:30 pm, with discussions often continuing until midnight, Banik says. “Fedorov is a huge workaholic, but he's a great boss; we were unafraid to take on hard challenges.”

COURTESY OF MINISTRY OF DIGITAL TRANSFORMATION Since the war began, the ministry’s challenges and working hours have grown further. “These 15 days of war are like one very long day that never ends,” Ionan, the deputy minister, recently remarked. She and others have scrambled to adapt platforms and relationships developed to serve dreams of e-government into tools to attack Russia and support Ukraine’s besieged population. Melnyk, the ministry adviser, began working on the campaign to pressure tech giants to cut off Russia on the same day the first explosions rocked Kyiv. He sent his first request to Apple, where he had good connections after working on a 2021 agreement for the company to support the Diia app and offer training to teachers who use its devices. Fedorov tweeted out a copy of his letter to Apple CEO Tim Cook, requesting that the company prevent Russians from accessing the Apple Store. It was the first in a barrage of tweets Fedorov used to publicly entreat some 50 companies to suspend or limit Russian users’ access to their products. That campaign made smart use of the momentum created by sanctions levied by the US and other governments, and Russia’s renewed belligerence towards western tech companies, says Emerson Brooking, a senior fellow at the Atlantic Council. “Fedorov and the Ukrainian strategy provided the tip of the spear, consolidating all of this pressure,” he says. Within a week, Apple halted device sales in Russia, Meta blocked Russian state media accounts for Facebook users in the EU, and Twitter added warnings to all tweets linking to Russian state media. The constant stream of call-outs to pressure companies, from payment services to game studios, to sever all ties with Russia has been labeled the geopolitical equivalent of canceling. “That was his aim,” says Banik. “Fedorov said that we had to do everything to have digital companies leave Russia.” In a video published in early March, Fedorov, wearing a T-shirt and speaking in Russian in front of a crate of Starlink receivers, urged young Russian technology workers to rise up against Putin or “become pariahs.” Others at the ministry have repurposed its flagship app Diia. It now includes a way to quickly donate money to Ukraine’s military, a chatbot for submitting images and video of Russian troop movements, access to 24-hour TV coverage of the crisis, and a kids video channel to help families spending hours stuck sheltering from air strikes. The ministry has also channeled energy and ideas from Ukraine’s tech sector, which grew 20 percent in 2020 and is powered by a tradition of technical education and a recent boom in outsourcing from more expensive countries. Most ministerial staffers came from that tech background and still had strong ties with the Ukrainian technology scene, which they were able to leverage. “Some of the guys working there are my former employees, a few of them were partners for different projects,” says Sergii Vasylchuk, the founder of blockchain company Everstake, which helped the ministry set up a platform to receive donations in nine different cryptocurrencies. “It's people that will speak our common language.” Two days after Russia’s assault began, Fedorov posted a call for developers, designers, marketers, and security specialists to join a volunteer “IT Army” coordinated via an official Telegram channel. More than 300,000 people have now volunteered their skills and joined an official Telegram channel where the IP addresses of Russian companies and websites to target with DDoS attacks are shared daily. Other missions have included reporting pro-Russian social media accounts that are spreading false information about the war.

Deputy minister Valeriya Ionan’s job has changed dramatically since the war began. COURTESY OF MINISTRY OF DIGITAL TRANSFORMATION Three days into the war, Ukrainian tech outsourcer Stfalcon and smart-home security startup Ajax Systems offered to build a smartphone app to expand the reach of the country’s air raid warning system. Parts of that aging system date from Soviet times, and many towns and villages are not covered. Ionan, the deputy minister, helped connect the companies with Ukraine’s civil defense force, which operates the largely analog warning system. The force’s operators, who manually turn on the sirens when the military radios in alerts, now also tap or click a webpage to send a digital signal to the Air Alert app used by more than 2 million Ukrainians. The ministry helped Google use the feed from Ajax’s system to send alerts directly to all Android phones in Ukraine. “It’s an ad hoc but very needed solution,” Ionan says. The ministry’s wartime projects can seem both surprising and sensible. After nearly two decades of Facebook and a pandemic that forced more of life online, it's no huge leap for a country to turn to apps, crowdsourcing, and social media growth hacking as part of its defense strategy—much like it feels reasonable that government services should move online. “What they are doing is not just PR campaigns, they're also accomplishing real things that benefit the Ukrainian resistance and support Ukrainian citizens,” says Lokot, the Dublin City professor. Whatever gains Russia’s military achieves on the ground in Ukraine over the coming weeks, Fedorov and his ministry will be at the heart of Ukraine’s response. Despite the ministry’s nimble online work and doughty conventional fighting by Ukraine’s military, Russia's attacks have intensified, and some cities and towns have been captured by Russian forces. Food, water, and medical supplies are hard to access in some Ukrainian cities. “The information war matters less as time goes on,” says Brooking, of the Atlantic Council. “The realities and calculations of war itself are now driving this conflict.” Tom Simonite is a senior writer for WIRED in San Francisco covering artificial intelligence and its effects on the world. He once trained an artificial neural network to generate seascapes and is available for commissions. Simonite was previously San Francisco bureau chief at MIT Technology Review, and wrote and edited... Read more Gian M. Volpicelli is a senior writer at WIRED, where he covers cryptocurrency, decentralization, politics, and technology regulation. He received a master’s degree in journalism from City University of London after studying politics and international relations in Rome. He lives in London. More Great WIRED Stories

© 2022 Condé Nast. All rights reserved. Use of this site constitutes acceptance of our User Agreement and Privacy Policy and Cookie Statement and Your California Privacy Rights. Wired may earn a portion of sales from products that are purchased through our site as part of our Affiliate Partnerships with retailers. The material on this site may not be reproduced, distributed, transmitted, cached or otherwise used, except with the prior written permission of Condé Nast. Ad Choices |

|

|

| The text being discussed is available at and |

|

SITE COUNT< Blog Counters Reset to zero January 20, 2015 | TrueValueMetrics (TVM) is an Open Source / Open Knowledge initiative. It has been funded by family and friends. TVM is a 'big idea' that has the potential to be a game changer. The goal is for it to remain an open access initiative. |

| WE WANT TO MAINTAIN AN OPEN KNOWLEDGE MODEL | A MODEST DONATION WILL HELP MAKE THAT HAPPEN | |

|

The information on this website may only be used for socio-enviro-economic performance analysis, education and limited low profit purposes

Copyright © 2005-2021 Peter Burgess. All rights reserved. Last modified 04/05/2025 19:48:21 | ||