OVERVIEW

MANAGEMENT

PERFORMANCE

POSSIBILITIES

CAPITALS

ACTIVITIES

ACTORS

BURGESS

|

INFLATION

ISSUE ... REAL ROOT CAUSES BEING IGNORED NYT ... Inflation Continued to Worsen in March, as Gas and Rent Costs Rose

Year-over-year percent change in the Consumer Price Index ... Source: Bureau of Labor Statistics Original article: https://www.nytimes.com/live/2022/04/12/business/cpi-inflation-report#food-prices-grocery Peter Burgess COMMENTARY Peter Burgess | ||

Inflation Continued to Worsen in March, as Gas and Rent Costs Rose

April 12, 2022

Here’s what you need to know:

Inflation hit 8.5 percent in the United States last month, the fastest 12-month pace since 1981, as a surge in gasoline prices tied to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine added to sharp increases coming from the collision of strong demand and stubborn pandemic-related supply shortages. Fuel prices jumped to record levels across much of the nation and grocery costs soared, the Labor Department said Tuesday in its monthly report on the Consumer Price Index. The price pressures have been painful for American households, especially those that have lower incomes and devote a big share of their budgets to necessities. But the news was not uniformly bad: A measure that strips out volatile food and fuel prices decelerated slightly from February as used car prices swooned. Economists and policymakers took that as a sign that inflation in goods might be starting to cool off after climbing at a breakneck pace for much of the past year. Given the pop in gasoline prices in March, “these numbers are likely to represent something of a peak,” said Gregory Daco, the chief economist at Ernst & Young’s strategy consultancy, EY-Parthenon. Still, he said, it will be crucial to watch whether price increases excluding food and fuel — so-called core prices — slow down in the months ahead. Core prices climbed at a brisk 6.5 percent in the year through March, up from 6.4 percent in the year through February. Even so, it slowed down a bit on a monthly basis, rising 0.3 percent from February, compared with 0.5 percent the prior month. There are a few hopeful signs that inflation could slow in the months ahead. The first is largely mechanical. Prices began to pop last spring, which means changes will be measured against a higher year-ago number in the months ahead. More fundamentally, March’s data showed that prices for some goods, including used cars and apparel, moderated or even fell — though the signal was somewhat inconsistent, with furniture prices rising sharply. If rapid inflation in prices for goods does wane, it could help overall inflation subside. The critical question is how much and how quickly prices will come down, and recent developments ramp up the risks that uncomfortably rapid inflation could linger. Services costs, including rent and other housing expenses, are increasing more rapidly. Those measures move slowly, and are likely to be a major factor determining the course of inflation. Wages are up sharply, pushing costs up for employers and potentially prompting them to lift prices. Businesses may feel that they have the power to pass rising costs along to customers, and even to expand their profits, because consumers have continued to spend during a full year of rapid price increases. And cheaper goods are not guaranteed. A coronavirus outbreak is shuttering cities and disrupting production in China, and the war in Ukraine adds a huge dose of uncertainty about commodity prices and supply chains. — Jeanna Smialek ----------------------------------- Inflation Hits Fastest Pace Since 1981, at 8.5% Through March A top Fed official says moderation in monthly core inflation is ‘welcome.’

Lael Brainard, a Federal Reserve governor, in Washington last year.Credit...Al Drago for The New York Times Lael Brainard, a Federal Reserve governor who is the Biden administration’s nominee to serve as the central bank’s vice chair, highlighted a slight cooling in monthly inflation outside of food and fuel as a welcome sign to economic policymakers. Consumer Price Index data released Tuesday showed inflation running at 8.5 percent in the year ending in March, the fastest pace since 1981. Ms. Brainard acknowledged the pain that high inflation was causing families, while noting that a big chunk of last month’s jump was tied to the pop in energy prices that followed Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. And Ms. Brainard particularly emphasized that the core inflation rate, which strips out the volatile prices of food and fuel, was slightly lower on a monthly basis. That came as price increases for goods decelerated sharply, driven lower by a bigger-than-expected decline in used car prices. “It’s very welcome to see the moderation in this category,” Ms. Brainard said of the core goods numbers. “I’ll be looking to see whether we continue to see moderation in the months ahead.” She would not put too much weight on any one month’s number, she said, but added that she would watch to see if a declining number of product categories posted outsize price increases in the months ahead. Fed officials began raising interest rates last month to rein in lending, spending and demand, hoping to prevent rapid price increases from becoming a more permanent feature of the U.S. economy. Ms. Brainard, speaking on a Wall Street Journal livestream, said on Tuesday that the Fed would continue to reduce its support for the economy “methodically,” and that it might confirm a plan to shrink its balance sheet of bond holdings as soon as May, with the shrinking itself starting in June. That policy would reinforce rate increases by pushing borrowing costs higher. Between higher interest rates and slowing support from the government, Ms. Brainard said she was expecting a cool-down in consumer spending. “The forward trajectory of demand is set to moderate,” she said. — Jeanna Smialek ----------------------------------- Republicans try to pin blame on the Biden administration for rising costs.

Rising inflation has dampened President Biden’s approval ratings ahead of the midterm elections in November.Credit...Kenny Holston for The New York Times Republicans seized on new numbers showing a spike in inflation last month, blaming Democrats for the rise in prices and urging Americans to support Republican candidates in the upcoming midterm elections. Consumer prices increased 8.5 percent in the year through March, the fastest inflation rate in 41 years, according to Labor Department data released on Tuesday. The increase was fueled by a jump in gas prices tied to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, along with rising costs for food and rent. “Under President Biden, prices are accelerating faster than any time in more than 40 years, sucking up paychecks and draining savings,” Representative Kevin McCarthy, the House Republican leader, said on Twitter. Representative Jason Smith of Missouri, the top Republican on the House Budget Committee, claimed that Americans would be “stuck in this inflation nightmare” if Democrats continued to control both chambers of Congress. Global supply-chain disruptions, strong demand for goods and pent-up savings have led to the surge in prices. A recent Gallup poll found that inflation was the top economic concern for Americans, with 17 percent citing it as the nation’s most important issue. Although the economy has seen strong growth in the labor market, recovering millions of jobs lost during the pandemic, those gains have been overshadowed by inflation, which has also outpaced overall wage growth, wiping out those gains for many workers. The issue has dampened consumer sentiment and Mr. Biden’s approval ratings ahead of the midterm elections in November. A recent CBS News poll found that higher prices have been a difficulty for 66 percent of people surveyed and more than half were cutting back spending on food and groceries. Jen Psaki, the White House press secretary, said on Monday that officials expected headline inflation numbers to be “extraordinarily elevated.” She blamed the increase in gas prices on Russian President Vladimir Putin’s decision to invade Ukraine. Still, Ms. Psaki said the White House had to enact more policies to help Americans deal with the rising costs. In a bid to bring down prices, President Biden is expected to announce a plan to allow higher-ethanol gasoline blends on Tuesday, and last month he said the U.S. would release one million barrels of oil a day from the U.S. Strategic Petroleum Reserve over the next six months. David McIntosh, the president of the conservative Club for Growth political action committee, said the White House was placing outsize blame on Mr. Putin’s actions and that the Biden administration’s “reckless spending, counterproductive energy regulations and unnecessary Covid restrictions” had led to the spike in prices. “While Democrats are trying to pretend that Biden’s inflation is all due to Putin, the fact is American voters aren’t buying it,” Mr. McIntosh said in a statement. — Madeleine Ngo ----------------------------------- Food prices jumped, driven by markups at the grocery store.

Food prices continued to climb in March as farmers and grocers passed on rising costs to customers.Credit...Gabby Jones for The New York Times Food prices continued to climb in March as farmers and grocers passed on rising costs for fertilizer, transportation and other inputs in their supply chains. An index of food prices rose 8.8 percent in March from the prior year, the biggest annual increase since 1981, driven by an increase in the price of meat, poultry, fish and eggs. The price of beef rose 16 percent from last year, while the price of flour grew 14.2 percent, citrus fruits grew 19.5 percent and milk increased 13.3 percent. The overall food price index was up 1.0 percent from the previous month, the same rate of increase seen in February but an acceleration from the months before that. Especially when combined with soaring prices for housing, the price increases will take a toll on America’s poorest households, who spend a large share of their income on food and rent. But the effect of government aid programs, targeted at feeding the poor, were also evident. Prices for food at employee sites and schools plummeted 30.5 percent over the past year, reflecting more widespread free lunch programs. Russia’s invasion of Ukraine has sparked worries about the global food supply, given that both countries are important sources of wheat, barley, fertilizer, sunflower oil and other products. Global food prices hit a record high in March, according to an index maintained by the United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization. The index rose nearly 13 percent from the previous month, as the war sent prices of grains and edible oils soaring. Still, economists said the inflationary effects of rising food prices were, for now, more concentrated in Europe, the Middle East and Africa, markets that depend on direct imports of Ukrainian wheat and other goods. In the United States, which is an agricultural exporter, rising food prices are still mainly driven by pre-existing trends, such as rising costs for transportation, fertilizer, crop insurance and chemicals. Adam S. Posen, the president of the Peterson Institute for International Economics, said the Russian invasion of Ukraine had little direct effect on the United States in terms of energy and food but “very meaningful” effects in other parts of the world. Those effects would gradually spill over into the U.S. economy, Mr. Posen suggested, as prices rose elsewhere and American consumers imported higher-cost goods. “I would expect over the next few months to feel the pain from others passing toward us,” he said. — Ana Swanson ----------------------------------- The surge in gas prices accounted for over half of the monthly increase in inflation.

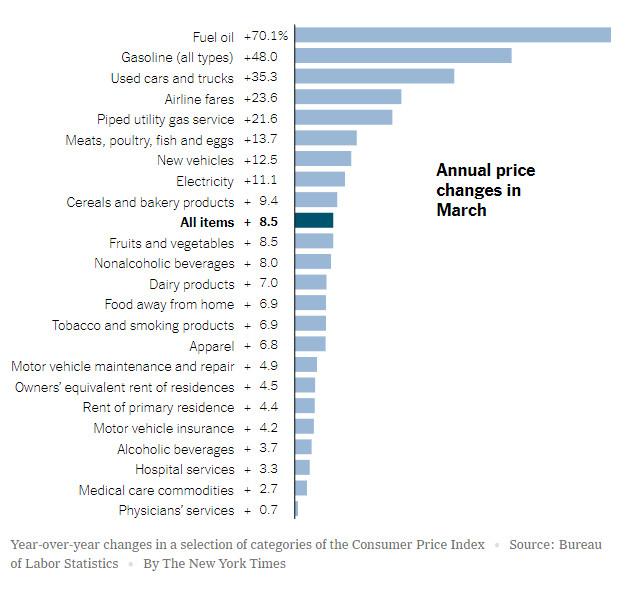

For the year through March, gasoline prices rose 48 percent. Credit...Gabby Jones for The New York Times For nearly a year, broadening inflation has unsettled consumers, gripped financial markets and tested policymakers. And now energy prices — particularly for gasoline and diesel — have become the leading driver. The Consumer Price Index data released Tuesday showed a whopping 18.3 percent increase in gasoline prices in March from the prior month, seasonally adjusted, accounting for over half of the overall monthly increase in the index. For the year through March, gasoline prices rose 48 percent. Energy prices overall increased 11 percent compared with February and 32 percent in the last 12 months.

Year-over-year changes in a selection of categories of the Consumer Price IndexSource: Bureau of Labor Statistics ... By The New York Times The most recent jump in energy costs has been directly tied to the war in Ukraine, keeping inflation significantly higher for American households for much longer than policymakers had hoped. The U.S. ban on Russian oil imports — which was announced in March and goes into full effect this month — has shaken global energy markets and already caused trouble for American consumers and businesses in both direct and roundabout ways. In addition to gasoline, commercial transportation, utilities, fertilizers and more have shot up in price. “The good news is that the spike in oil prices was short-lived, and if today’s relatively lower prices hold, then fuel prices should eventually follow and relieve some of the pressure we saw in March,” said Clay Seigle, a Houston-based energy strategist and vice president of the U.S. Association for Energy Economics. “The bad news is that’s not likely. Instead, oil prices will continue to swing sharply, and more spikes are likely as the war continues.” In recent years, gasoline and utilities costs as a share of income averaged 28 percent for households in the bottom-fifth of earners, according to research conducted by economists at Deutsche Bank using government data. According to estimates from National Energy Assistance Directors’ Association, those expenses as a share of income have probably jumped to 33.5 percent. Utility expenses for the average household for the period stretching from October to March have surged in comparison with the same period a year prior. Natural gas expenses increased to about $800 from $573; heating oil climbed to $1,900 from about $1,200; and propane rose to about $1,600 from $1,158. — Talmon Joseph Smith ----------------------------------- Biden will allow summertime sales of higher-ethanol gas.

Credit...Brian Snyder/Reuters WASHINGTON — President Biden announced on Tuesday a plan to suspend a ban on summertime sales of higher-ethanol gasoline blends, a move that White House officials said was aimed at reducing gas prices but that energy experts predicted would have only a marginal impact at the pump. The Environmental Protection Agency will issue a waiver that would allow the blend known as E15 — which is made of 15 percent ethanol — to be used between June 1 and Sept. 15. The White House estimated that approximately 2,300 stations in the country offer the blend and cast the decision as a move toward “energy independence.” “E15 is about 10 cents a gallon cheaper,” Mr. Biden said, speaking after taking a tour of a production facility that produces 150 million gallons of bioethanol annually. “And some gas stations offer an even bigger discount than that.” “When you have a choice, you have competition,” Mr. Biden added. “When you have competition, you have better prices.” The decision to lift the summertime ban comes as Mr. Biden faces growing pressure to bring down energy prices, which helped drive the fastest rate of inflation since 1981 in March. A gallon of gas was averaging $4.10 on Tuesday, according to AAA. Last month, the president announced a plan to release one million barrels of oil a day from the U.S. Strategic Petroleum Reserve over the next six months. Ethanol is made from corn and other crops and has been mixed into some types of gasoline for years as a way to reduce reliance on oil. But the blend’s higher volatility can contribute to smog in warmer weather. For that reason, environmental groups have traditionally objected to lifting the summertime ban, as have oil companies, which fear greater use of ethanol will cut into their sales. How much the presence of ethanol holds down fuel prices has been a subject of debate among economists. Some experts said the decision was likely to reap larger political benefits than financial ones. “This is still very very small compared with the strategic petroleum reserve release,” said David Victor, a climate policy expert at the University of California, San Diego. “This one is much more of a transparently political move.” Lawmakers in corn-producing states have been urging Mr. Biden to use biofuels to fill the gap created by the United States ban on importing Russian oil. Oil refiners are required to blend some ethanol into gasoline under a pair of laws, passed in 2005 and 2007, intended to reduce the use of oil and the creation of greenhouse gases by mandating increased levels of ethanol in the nation’s fuel mix every year. However, since passage of the 2007 law, the mandate has been met with criticism that it has contributed to increased fuel prices and has done little to reduce greenhouse gas pollution. A study last month in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences estimated that corn-based ethanol was at least 24 percent more carbon-intensive than gasoline when emissions from land-use changes to grow corn, along with processing and combustion, were included. “Corn ethanol is a greater emitter of greenhouse gases than gasoline,” said Jason Hill, a professor of bioproducts and biosystems engineering at the University of Minnesota. “This will actually work in the opposite direction of the administration’s climate goals rather than being a benefit,” Mr. Mills said. A White House senior administration official on Monday pushed back on that study, arguing that “a number of analyses” have that shown corn-based ethanol cuts greenhouse gas emissions more than 40 percent compared with gasoline. — Lisa Friedman and Michael D. Shear ----------------------------------- Pay raises aren’t keeping up with inflation.

Over the pandemic as a whole, workers on average have seen their inflation-adjusted earnings rise — just not as quickly as they were rising before the pandemic.Credit...Gabby Jones for The New York Times American workers are experiencing their fastest wage gains in years — but pay raises still aren’t keeping up with inflation on average. Average hourly earnings for all workers were up 5.6 percent in March, according to the Labor Department. But prices rose 8.5 percent — which means that, adjusted for inflation, average pay was actually down by 2.7 percent. For rank-and-file workers — what the government calls “production and nonsupervisory employees” — hourly pay was down 2.4 percent after adjusting for inflation. Other, more sophisticated measures of wage growth likewise show price increases outpacing pay raises. Not all workers are losing ground. Waiters, hotel maids and other nonmanagement employees in leisure and hospitality have seen their pay rise by nearly 15 percent over the past year, well ahead of inflation. The same is true in other service industries where employers have been increasing wages to try to attract workers. And over the pandemic as a whole, workers on average have seen their inflation-adjusted earnings rise — just not as quickly as they were rising before the pandemic. If wage growth keeps lagging behind inflation, that could force some consumers to pull back on spending. Reduced demand for goods and services could, in turn, lead businesses to cut prices — or at least raise them more slowly — causing inflation to moderate. But it may not be that simple. Rapid job growth and strong demand for labor mean that more people are working, and they’re working more hours. That means that Americans, in the aggregate, are earning more money, even if their hourly pay isn’t keeping up with inflation. That could keep consumer demand strong in the face of inflation. — Ben Casselman ----------------------------------- The Fed prepares to raise rates quickly as high inflation lingers.

The Federal Reserve is expected to raise interest rates by half a percentage point next month.Credit...Pete Marovich for The New York Times A full year of rapid inflation has prodded the Federal Reserve to pivot from cushioning the economy to quickly withdrawing support from it. The latest monthly reading from the Consumer Price Index, which showed prices climbing at the fastest pace since 1981, is likely to keep it on that course. Fed officials expected inflation to fade quickly when it began to accelerate last spring, but that has been slow to happen. Tuesday’s data offered hopeful signs that prices outside of energy might be moderating on a monthly basis, but it remains unclear how much and how quickly price increases will slow down amid continued supply chain disruptions and as pressures broaden into service categories, like rent. The central bank began raising interest rates last month and projected a series of policy moves to come, changes that will make money more expensive to borrow in a bid to slow shopping and business investment. The theory is that weaker demand will help supply to catch up, helping to tame the burst of inflation. The Fed is trying to tamp down price increases before consumers and businesses come to expect them year after year and begin to act accordingly, which would make quick inflation a more lasting feature of the economy. The central bank hopes to temper demand without slowing down the job market so much that a recession becomes inevitable — although officials acknowledge that achieving such a positive outcome will be challenging. Central bankers are expected to increase interest rates by half a percentage point at their meeting in early May, with another large move possible in June. They have indicated that they will soon begin to quickly shrink their balance sheet of bond holdings, another policy that should push interest rates higher and slow demand. “It’s been a shock: We went for a decade when we could not get inflation to 2 percent,” Christopher J. Waller, a Fed governor, said during an event on Monday. “We’re hoping that it will go away relatively fast. That’s our job, and we’re going to get it done.” Central bankers might be encouraged by the fact that the Consumer Price Index’s so-called core measure, which strips out volatile food and fuel prices, climbed a more modest 0.3 percent in March from the prior month after a 0.5 increase in February. That slowdown came as used vehicle prices fell. Even so, Fed officials have become concerned that fast price increases could last longer as lockdowns in China threaten to perpetuate supply chain issues. The war in Ukraine presents another wild card that could affect the supply of important products like grain and gasoline. At the Fed’s March meeting, “participants agreed that uncertainty regarding the path of inflation was elevated and that risks to inflation were weighted to the upside,” according to minutes from the gathering released last week. — Jeanna Smialek ----------------------------------- Wall Street loses its footing after the C.P.I. report delivers mixed news.

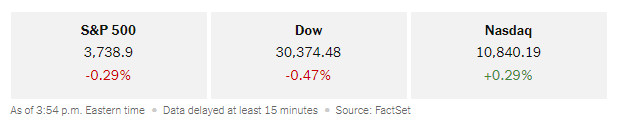

Wall Street edged lower on Tuesday, as investors digested the latest Consumer Price Index data, which showed another big rise in inflation in March. The S&P 500 ended the day down 0.3 percent, reversing earlier gains. The yield on 10-year U.S. Treasury notes, a benchmark for borrowing costs across the economy, dropped about six basis points, to about 2.72 percent. The new data showed prices rose 8.5 percent in the year through March, slightly higher than economists had expected. The number could make the Federal Reserve speed up its plans to raise interest rates as it tries to cool down the economy. Core inflation, which strips out the volatile fuel and food categories, slowed slightly, however, rising 0.3 percent in March from February — good news for the Fed because it showed that prices were moderating somewhat. “At this point, it is hard to imagine more justification is needed for further Fed action beyond a four-decade high in inflation,” Lindsey Piegza, chief economist at Stifel, wrote in a note. “As such, the market is widely anticipating a half of a percentage point increase.” Investors also reacted to the latest remarks from Lael Brainard, a Federal Reserve governor, who reiterated on Tuesday that the central bank could take a more aggressive approach toward easing inflation and confirmed a plan to shrink its balance sheet of bond holdings as soon as May. Ms. Brainard said she would keep an eye on whether core monthly inflation continued to cool down in the months ahead. The inflation data captured the effects of soaring gas prices, which climbed to their highest levels since 2008 in March. Many companies would not buy Russian energy after the country’s invasion of Ukraine, even before the United States announced a ban Russian energy imports and Europe moved to dramatically reduce its reliance on Russian gas and oil. Russia is the third-largest producer of oil, and crude prices spiked, followed by gas prices, which hit a record high in early March and kept rising. Gasoline prices in the U.S. have settled since, following oil lower. But oil prices rose more than 6 percent on Tuesday. European stock indexes were lower, with the Stoxx Europe 600 down 0.4 percent. In Asia, stocks ended the day mixed, with the Nikkei in Japan losing 1.8 percent, while the Hang Seng in Hong Kong gained 0.5 percent. — Coral Murphy Marcos ----------------------------------- Price pressures are easing for some goods, but supply chains face new disruptions.

A Shanghai neighborhood under lockdown last month. Lockdowns in China risk causing further product shortages in the United States.Credit...Qilai Shen for The New York Times Price pressures for household goods, apparel, vehicles and other items showed signs of cooling in March, as companies built up extra inventories of products in storerooms and warehouses and shortages abated. The monthly price increase in a basket of core goods has leveled off, decelerating from a growth rate of 1 percent in recent months to a 0.4 percent decline in March. The price of used cars and trucks fell 3.8 percent in March from the month before, and the price of new cars and trucks grew 0.2 percent. The price of household furnishings and supplies rose 1 percent in March, the eighth consecutive monthly increase in that category. But the disruptions that have plagued supply chains continue to show signs of worsening, suggesting that American consumers may see more shortages of products like electronics — and potentially renewed price increases — in the months to come. In particular, sweeping lockdowns in China to try to stamp out the Omicron variant of the coronavirus have been posing new risks to America’s supply of manufacturing components and finished goods. Although China has tried to keep its ports functioning through the pandemic, restrictions on truck drivers have stemmed the flow of electronics, car parts and other goods out of the country. Ariane Curtis, global economist at Capital Economics, said in a note last week that, in developed markets, “renewed shortages — particularly of electrical goods — and higher shipping costs could keep goods inflation higher for longer than we currently expect.” Freight rates have dipped slightly in recent weeks, but they remain far higher than they were before the pandemic. The price to ship a 40-foot container from China to the West Coast of the United States was $15,817 as of Friday, up from $5,893 one year ago and from $1,584 at the same time in 2019, according to data from Freightos, a freight-tracking firm. Omair Sharif, the president of the research firm Inflation Insights, said it was impossible to accurately forecast how long Chinese lockdowns might continue to disrupt global supply chains and therefore what their inflationary impact would be. But companies have recently made progress building up inventories that were badly stretched earlier in the pandemic, he said, and those excess goods will help cushion the inflationary impact. Consumers also appear to be cutting back their spending on goods, probably to offset higher food and gasoline prices, Mr. Sharif said. “People are pulling back because of inflation and high prices elsewhere, so stuff is starting to pile up a bit at the warehouses,” he said. “With inventories we are definitely in a better position to handle a slowdown without a big knock-on effect on inflation.” Some car industry experts have said that inventory improvement in used cars could be partly a seasonal trend and that new car prices may have moderated because manufacturers have been cracking down on dealers who charge above list prices. Phil Levy, the chief economist at Flexport, a logistics company, said there was “tremendous concern within the logistics industry that companies have overdone it on orders, are accumulating excess inventories” and will pull back. But the forecast for inflation is complex, he said, since much of what happens will hinge on consumer demand. “The crystal ball is unusually murky right now,” Mr. Levy said. — Ana Swanson ----------------------------------- Globally, inflation is surging amid persistent pandemic disruptions and war in Ukraine.

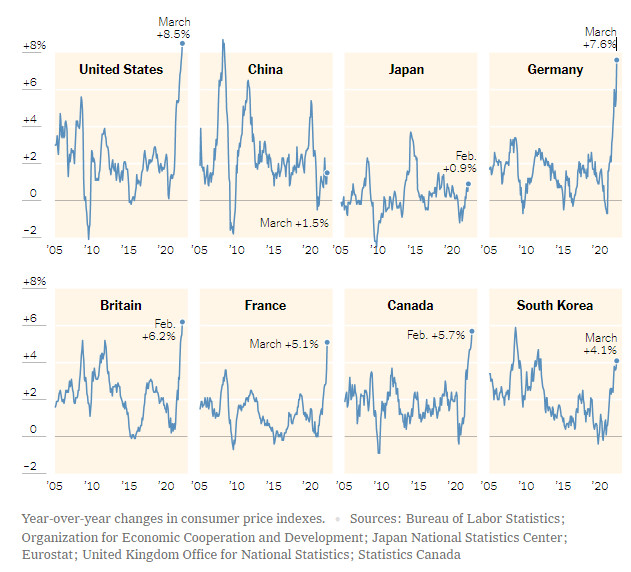

Year-over-year changes in consumer price indexes.Sources: Bureau of Labor Statistics; Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development; Japan National Statistics Center; Eurostat; United Kingdom Office for National Statistics; Statistics Canada Just as in the United States, policymakers in other countries have been caught off guard by persistently high inflation. Price increases were expected to ease as economies recovered from the pandemic, but surging energy and food prices have continued to lift inflation around the world. After Russia invaded Ukraine, predictions about inflation were torn up and reset much higher in light of rising commodity prices. The war sparked fears about the stability of energy supplies from Russia, which are crucial to Europe, and disrupted food production, raising the risk of a global hunger crisis. Meanwhile, supply chains remain burdened by pandemic-induced disruptions, and demand for some goods is still stronger than production can handle. High inflation is widespread: Among the United States, the euro area and other so-called advanced economies, 60 percent of the countries have annual inflation rates over 5 percent, according to the Bank for International Settlements, a bank for central banks. It is the largest share since the 1980s and a serious problem for central banks, which typically target inflation at 2 percent. In emerging economies, more than half the countries have inflation rates above 7 percent, the bank said. For now, China and Japan are notable exceptions. “We may be on the cusp of a new inflationary era,” Agustín Carstens, the head of the bank, said last week. “The forces behind high inflation could persist for some time.” After central banks in the United States and Europe have been trying for more than a decade to raise inflation to their targets and keep it stable, policymakers are suddenly struggling to tame it. Energy and food prices are often volatile, but what worries central bankers is that price increases could spill over into other goods and services, followed by worker demands for higher wages to cope with the higher cost of living. In Britain, inflation is at its highest level in three decades. Economists surveyed by Bloomberg expect data published on Wednesday to show that prices in March climbed 6.7 percent from a year earlier. The Bank of England has already raised interest rates three times since December to their prepandemic level amid growing evidence that companies are responding to rising prices with higher wages. In the eurozone, the annual inflation rate jumped to 7.5 percent in March, up from 5.9 percent the previous month. Higher energy prices are the main driver of inflation there, with far fewer signs of significant wage increases. But the European Central Bank has set in motion a plan to end its extensive bond-buying program to pave the way for interest rate increases, because “inflation was becoming more broad-based and more persistent,” according to the account of its most recent policy meeting. Policymakers will meet again this week. Even in Japan, which has battled very low or negative inflation rates for decades, there is a sign that higher prices are reaching its shores. Last month, a government survey of consumers’ one-year inflation expectations rose to 2.7 percent, the highest since 2014. — Eshe Nelson ----------------------------------- Airfares add to price pressure as travel demand and fuel costs rise.

Travelers at Hartsfield-Jackson Atlanta International Airport. Consumers spent an estimated $8.8 billion on domestic flights last month, according to one analysis.Credit ... Alyssa Pointer for The New York Times Airfares are skyrocketing as the travel recovery strengthens and airlines struggle with rising fuel costs. Fares for domestic flights booked in March were 20 percent higher than in the same month in 2019, according to an analysis by the Adobe Digital Economy Index, which draws on online sales from six of the top 10 U.S. airlines. Fares were up only 5 percent in February from the same month in 2019, and were down 3 percent in January. “The unleash of pent-up demand has been a major driving factor, as the desire for air travel is coming back more aggressively than anticipated,” said Vivek Pandya, who led the analysis for Adobe, the software giant. Consumers spent an estimated $8.8 billion on domestic flights last month, according to the Adobe analysis, which was released on Tuesday. Compared with prepandemic travel patterns, destinations particularly popular among consumers who bought tickets last month for travel in April and May included Palm Springs, Calif., and several destinations in Florida and Hawaii. About two million people, on average, have been boarding flights, including international departures, each day in U.S. airports since mid-March, according to security screening data from the Transportation Security Administration. That’s roughly a 10 percent decline from a similar period in 2019. Hopper, a flight-booking app, recently estimated that the average price of a round-trip domestic flight is $330, up 40 percent from the start of the year. That large increase can be attributed to three factors, according to Hopper: the rise of the Omicron variant of the coronavirus last year, which scared some travelers away and depressed prices at the start of this year; a typical seasonal rise in prices; and the spike in the cost of jet fuel caused in large part by Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. In an analysis this month, Hopper said it expected fares to rise another 10 percent, to $360, through May. — Niraj Chokshi ----------------------------------- Understand Inflation and How It Impacts You

| The text being discussed is available at | https://www.nytimes.com/live/2022/04/12/business/cpi-inflation-report#food-prices-grocery and |