OVERVIEW

MANAGEMENT

PERFORMANCE

POSSIBILITIES

CAPITALS

ACTIVITIES

ACTORS

BURGESS

|

A SUSTAIBABLE WORLD

THE FSG INITIATIVES The Essential Link Between ESG Targets & Financial Performance ... It’s key to building a sustainable business model.

Karina Sharpe Original article: https://hbr.org/2022/09/the-essential-link-between-esg-targets-financial-performance Peter Burgess COMMENTARY More than 25 years ago the idea of the 'Triple Bottom Line (TBL)' was promulgated by John Elkington and had some acceptance from a number of well respected companies. There was however considerable resistance to widespread adoption of the thinking and making TBL style reporting a legally enforceable requirement. Over time the idea of ESG analysis emerged ... that is Environmental, Social and Governance performance analysis emerged. ESG served to sideline TBL analysis and reporting. There is now ... in 2023 ... a robust conversation about ESG in professional and business circles and virtually nothing about TBL. I have been bothered by this from the first emergence of ESG into the management analysis space several years ago. The strength and the value of the original TBL was that there was linkage between the profit performance, the social performance and the environmental performance of the reporting entity. ESG completely avoids any linkage between the ESG elements and profit performance. This is consequential because in many if not most business situations maximizing profit performance will have substantial adverse impact on social and environmental performance. The speed with which ESG has become the 'go to' reporting framework for factors beyond profit performance does not come as a surprise. Better management reporting is going to come at some point in time, and maybe quite soon, and the embrace of ESG is happening because it has the potential to delay new and better reporting requirements by business entities that are much more rigorous. I qualified as a Chartered Accountant in the UK (ACA 1966) and had my first CFO employment in the USA before I was 30 years old. That was more than 50 years ago. I have engaged with emerging new technology for a very long time and am disturbed by the reality that the functioning of the business world has trended to more and more opaqueness rather than to more transparency over the past several decades. This is unfortunate and more than anything else it is enabling business behavior that has and is accelerating inequality in all its many manifestations. I am disappointed that the accountancy profession has not stepped up to modernize corporate reporting to make it more fit-for-purpose for the 21st century. I was trained by one of the big accounting firms in London in the 1960s, but the big firms in the modern accountancy profession do not seem to have the same commitment to professional ethics that was the norm when I was training. I think this is summed up by something that was said to me at a reunion about 20 years after I quallified ... 'Accounting is no longer a profession ,,, it is a business!'. I was working on a World Bank / UN assignment some years later in Africa where financing was needed and issues were many. The Government in the country despatched the local partner of what had been my old firm in London to admonish me regarding the information I was looking to have. I remember taking umbrage at the character of this professional intervention because it would not have happened in the office where I trained ... and there was no way I was going to get diverted from what I considered to be my professional responsibility. But the question gets to be how much of this professional rot exists in the big name and wealthy accountancy firms. And maybe we have to ask whether or not the young professional of today would actually recognise an unacceptable practice if they came across it in their work ... maybe not so much because they did it intentionally but more because modern professional practices are no longer fit-to-purpose in a more tech-intensive business ecosystem. I know I am bothered by the lack of transparency in the typical big company, and the opacity there is around most every product that customers buy and consume. I would have thought that professional accountants could be doing a much better job of creating a far better socio-enviro-economic information ecosystem that is more fit for purpose in this 21st century. Peter Burgess | ||

|

Sustainable Business Practices

The Essential Link Between ESG Targets & Financial Performance It’s key to building a sustainable business model. Written by Mark R. Kramer and Marc W. Pfitzer From the Magazine (September–October 2022) Summary. In recent years tremendous progress has been made in standardizing and quantifying measures of companies’ performance on environmental, social, and governance (ESG) criteria. There has also been a surge in investor interest in companies that are rated highly on ESG performance or appear to be taking ESG goals seriously. Yet surprisingly few companies are making meaningful progress in delivering on their ESG commitments. Of the 2,000 global companies tracked by the World Benchmarking Alliance, most have no explicit sustainability goals, and among those that do, very few are on track to meet them. Even companies that are making progress are, in most cases, merely instituting slow and incremental changes without the fundamental strategic and operational shifts necessary to meet the Paris Agreement or the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals. If companies neither integrate ESG factors into internal strategy and operational decisions nor communicate with investors about how improvements in ESG performance affect corporate earnings, then their claims about progress on sustainability goals are, at best, mere public relations—and at worst, deliberate misdirection. A few companies—including Sweden-based homebuilder BoKlok; Enel, the Italy-based electric utility; South Africa-based insurer Discovery; Mars Wrigley, the candy and chewing gum division of Mars; and food giant Nestlé—are building sustainability into their strategy and operations by connecting financial and social performance. (Disclosure: These companies have been clients of our firm, FSG, or sponsors of its Shared Value Initiative.) This article offers a six-step process that other companies can use to fully integrate ESG performance into their core business models. The Problem with Separate Systems Over more than 20 years of researching and working on sustainability issues with Fortune 100 companies around the world, we’ve found that when the measurement and accountability system for ESG performance is entirely divorced from the one that defines profitability and determines share price, leaders become blinded to the interdependence between the two types of performance. Indeed, the heightened attention to ESG reporting has not, for the most part, changed the way companies make decisions about strategy and capital investment. Nor has it helped reveal the tensions and opportunities that arise from understanding how ESG performance affects corporate profitability. As a result, most companies still treat sustainability as an afterthought—a matter of reputation, regulation, and reporting rather than as an essential component of corporate strategy. Capital allocation and operational budgeting decisions continue to be made in ways that lead to social and environmental damage, while firms rely on meager corporate social responsibility budgets, philanthropy, and public relations to retroactively remedy or deflect the problems that those decisions create. Consider ExxonMobil’s announcement that it aims to become “consistent with” the Paris Agreement by reducing the environmental impact of its operations. At the same time, the company intends to continue to invest heavily in new oil and gas properties. Existing ESG rating systems allow the company to report on only the emissions from its internal operations, without taking into account the environmental consequences of the oil and gas it sells. By that flawed measure, ExxonMobil ranks in the top quartile out of nearly 30,000 companies in consensus ESG ratings. Its much-publicized commitment of $15 billion to low-carbon solutions ignores the $256 billion in 2019 revenues that were entirely dependent on fossil fuels, which makes the company the fifth-largest producer of greenhouse gases (GHG) on the planet. In short, neither ExxonMobil’s massive impact on the planet nor the existential dilemma facing the company’s economic future are fully reflected in the ESG rating or factored into management’s strategic decisions. Or consider Tyson Foods, a producer of chicken, beef, and pork. In 2016 Tyson made a commitment to reduce its greenhouse gas emissions by 30% by 2030, but since then, its GHG emissions actually increased an average of 3% annually. Our analysis suggests that it is impossible for Tyson to fulfill its financial projections and simultaneously meet its stated ESG goals. Tyson is not alone. Numerous companies have made ESG commitments that are incompatible with business realities—and as long as ESG metrics and financial reporting are disconnected, these inconsistencies will continue. If companies are to move beyond mere posturing, leaders must confront the contradictions—and embrace the synergies—between profit and societal benefits and make the bold changes needed to actually deliver on the goals of the Paris Agreement and the United Nations’ 17 Sustainable Development Goals. Let’s look at the six-step process for doing that in detail. 1. Identify the ESG Issues Material to Your Company A good place to start is to consult the International Sustainability Standards Board’s listing of material ESG issues by industry, defined as “those governance, sustainability, or societal factors likely to affect the financial condition or operating performance of businesses within a specific sector.” In some cases, the link between material ESG issues and financial performance is simple and direct. The bulk of ExxonMobil’s revenues obviously come from its customers’ use of fossil fuels—even though it doesn’t report on greenhouse gas emissions generated by customers in its sustainability report. The most material issue for Discovery, a global life and health insurance company, is customer health, which directly affects its financial performance. But unlike ExxonMobil, Discovery confronts the connection between those issues head on. It uses a sophisticated set of rewards to encourage its subscribers (individuals and their dependents) to engage in healthier behaviors such as more exercise, better diets, and regular checkups. It tracks the cost of the incentives, their effectiveness in changing behavior, and the impact of behavior changes on medical costs and health outcomes. Discovery uses this approach to continuously optimize the relationship between customer health and the company’s bottom line. It has made numerous investments that differentiate it from other life and health insurers—such as giving its customers free Apple watches that enable the company to remotely monitor physical activity and track more than 11 million customer exercise readings per day. Promoting customer health as a core component of corporate strategy has created a unique competitive position and fueled Discovery’s global expansion and superior profitability relative to other insurers. Rigorous academic studies by RAND, Johns Hopkins, and others have shown that the medical costs of Discovery’s health insurance subscribers are 15% lower compared with those insured by local competitors, and the life expectancy of Discovery’s life insurance customers is 10 years longer. In other industries, the link between the social and environmental impact of a company’s actions and profits may be more complex. In the food and beverage sector, the nutritional value of the products sold is an obvious and direct material issue; what’s less visible are the operations of the suppliers of commodity inputs, which can represent 50% or more of all financial costs. Agricultural commodities like those Mars Wrigley uses are often sourced from smallholder farmers in South America, Africa, and Asia. While they offer a substantial cost advantage over commodities sourced from large-scale commercial growers in developed countries and generate income for smallholder farmers, the less sophisticated farming practices they use raise troubling social and environmental issues, including child labor, water scarcity, and deforestation, which accelerates climate change. In recent years tremendous progress has been made in standardizing and quantifying measures of companies’ performance on environmental, social, and governance (ESG) criteria. There has also been a surge in investor interest in companies that are rated highly on ESG performance or appear to be taking ESG goals seriously. Yet surprisingly few companies are making meaningful progress in delivering on their ESG commitments. Of the 2,000 global companies tracked by the World Benchmarking Alliance, most have no explicit sustainability goals, and among those that do, very few are on track to meet them. Even companies that are making progress are, in most cases, merely instituting slow and incremental changes without the fundamental strategic and operational shifts necessary to meet the Paris Agreement or the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals. If companies neither integrate ESG factors into internal strategy and operational decisions nor communicate with investors about how improvements in ESG performance affect corporate earnings, then their claims about progress on sustainability goals are, at best, mere public relations—and at worst, deliberate misdirection. A few companies—including Sweden-based homebuilder BoKlok; Enel, the Italy-based electric utility; South Africa-based insurer Discovery; Mars Wrigley, the candy and chewing gum division of Mars; and food giant Nestlé—are building sustainability into their strategy and operations by connecting financial and social performance. (Disclosure: These companies have been clients of our firm, FSG, or sponsors of its Shared Value Initiative.) This article offers a six-step process that other companies can use to fully integrate ESG performance into their core business models. The Problem with Separate Systems Over more than 20 years of researching and working on sustainability issues with Fortune 100 companies around the world, we’ve found that when the measurement and accountability system for ESG performance is entirely divorced from the one that defines profitability and determines share price, leaders become blinded to the interdependence between the two types of performance. Indeed, the heightened attention to ESG reporting has not, for the most part, changed the way companies make decisions about strategy and capital investment. Nor has it helped reveal the tensions and opportunities that arise from understanding how ESG performance affects corporate profitability. As a result, most companies still treat sustainability as an afterthought—a matter of reputation, regulation, and reporting rather than as an essential component of corporate strategy. Capital allocation and operational budgeting decisions continue to be made in ways that lead to social and environmental damage, while firms rely on meager corporate social responsibility budgets, philanthropy, and public relations to retroactively remedy or deflect the problems that those decisions create. Consider ExxonMobil’s announcement that it aims to become “consistent with” the Paris Agreement by reducing the environmental impact of its operations. At the same time, the company intends to continue to invest heavily in new oil and gas properties. Existing ESG rating systems allow the company to report on only the emissions from its internal operations, without taking into account the environmental consequences of the oil and gas it sells. By that flawed measure, ExxonMobil ranks in the top quartile out of nearly 30,000 companies in consensus ESG ratings. Its much-publicized commitment of $15 billion to low-carbon solutions ignores the $256 billion in 2019 revenues that were entirely dependent on fossil fuels, which makes the company the fifth-largest producer of greenhouse gases (GHG) on the planet. In short, neither ExxonMobil’s massive impact on the planet nor the existential dilemma facing the company’s economic future are fully reflected in the ESG rating or factored into management’s strategic decisions. Or consider Tyson Foods, a producer of chicken, beef, and pork. In 2016 Tyson made a commitment to reduce its greenhouse gas emissions by 30% by 2030, but since then, its GHG emissions actually increased an average of 3% annually. Our analysis suggests that it is impossible for Tyson to fulfill its financial projections and simultaneously meet its stated ESG goals. Tyson is not alone. Numerous companies have made ESG commitments that are incompatible with business realities—and as long as ESG metrics and financial reporting are disconnected, these inconsistencies will continue. If companies are to move beyond mere posturing, leaders must confront the contradictions—and embrace the synergies—between profit and societal benefits and make the bold changes needed to actually deliver on the goals of the Paris Agreement and the United Nations’ 17 Sustainable Development Goals. Let’s look at the six-step process for doing that in detail. 1. Identify the ESG Issues Material to Your Company A good place to start is to consult the International Sustainability Standards Board’s listing of material ESG issues by industry, defined as “those governance, sustainability, or societal factors likely to affect the financial condition or operating performance of businesses within a specific sector.” In some cases, the link between material ESG issues and financial performance is simple and direct. The bulk of ExxonMobil’s revenues obviously come from its customers’ use of fossil fuels—even though it doesn’t report on greenhouse gas emissions generated by customers in its sustainability report. The most material issue for Discovery, a global life and health insurance company, is customer health, which directly affects its financial performance. But unlike ExxonMobil, Discovery confronts the connection between those issues head on. It uses a sophisticated set of rewards to encourage its subscribers (individuals and their dependents) to engage in healthier behaviors such as more exercise, better diets, and regular checkups. It tracks the cost of the incentives, their effectiveness in changing behavior, and the impact of behavior changes on medical costs and health outcomes. Discovery uses this approach to continuously optimize the relationship between customer health and the company’s bottom line. It has made numerous investments that differentiate it from other life and health insurers—such as giving its customers free Apple watches that enable the company to remotely monitor physical activity and track more than 11 million customer exercise readings per day. Promoting customer health as a core component of corporate strategy has created a unique competitive position and fueled Discovery’s global expansion and superior profitability relative to other insurers. Rigorous academic studies by RAND, Johns Hopkins, and others have shown that the medical costs of Discovery’s health insurance subscribers are 15% lower compared with those insured by local competitors, and the life expectancy of Discovery’s life insurance customers is 10 years longer. In other industries, the link between the social and environmental impact of a company’s actions and profits may be more complex. In the food and beverage sector, the nutritional value of the products sold is an obvious and direct material issue; what’s less visible are the operations of the suppliers of commodity inputs, which can represent 50% or more of all financial costs. Agricultural commodities like those Mars Wrigley uses are often sourced from smallholder farmers in South America, Africa, and Asia. While they offer a substantial cost advantage over commodities sourced from large-scale commercial growers in developed countries and generate income for smallholder farmers, the less sophisticated farming practices they use raise troubling social and environmental issues, including child labor, water scarcity, and deforestation, which accelerates climate change. Mars Wrigley systematically tracks the carbon footprint and water intensity of the crops it purchases across the globe, along with farmers’ income. Its challenge is to maintain a cost advantage by sourcing from lower-income countries while reducing poverty and environmental harm. Applying this approach to its sourcing of mint from smallholder farmers in India, for example, has resulted in a 26% increase in farmers’ earnings and a 48% decrease in unsustainable water use, while allowing the company to sustain a significant cost advantage. 2. Focus on Your Strategy, Not on Reporting The greatest social and environmental impacts of any company will be the result of fundamental strategic choices rather than incremental operational improvements. Start-ups, unencumbered by the past, often find strategic advantages by rethinking industry business models in light of current knowledge. When Discovery first entered the insurance market almost 30 years ago, it leveraged the ways that diet and behavior influence health to invent a more profitable business model that was unlike that of its more established health insurance competitors. In seeking to tap into consumers’ concern about climate change, Tesla used new software and technology to invent the first popular electric vehicle. But many long-established companies still operate with business models that were developed decades—even centuries—ago, when leaders were unaware of or routinely ignored the impact that their businesses had on social conditions and the environment. They react to ESG issues only at the eleventh hour and are therefore poorly positioned to compete in a world where social and environmental impact drives shareholder value. Virtually all incumbent automobile companies are now scrambling to catch up with the demand for electric vehicles after decades of focusing on incrementally improving the miles-per-gallon performance of their vehicles or reducing factory emissions. That is exactly the kind of strategic shift at the core of the business model that companies in every industry will need to make—and quickly. The best way to ensure that your company is addressing its material social and environmental challenges is to relinquish your focus on modest change and improvements in reporting and, instead, identify and pursue bold new opportunities. Confront the fundamental question of how you will reinvent your business model and differentiate your company from competitors by building positive social and environmental outcomes into your strategy. Communicating a clear and compelling competitive strategy to create shared value—how you will pursue financial success in a way that also yields societal benefits—will carry far more weight with investors than marginal improvements in ESG metrics.

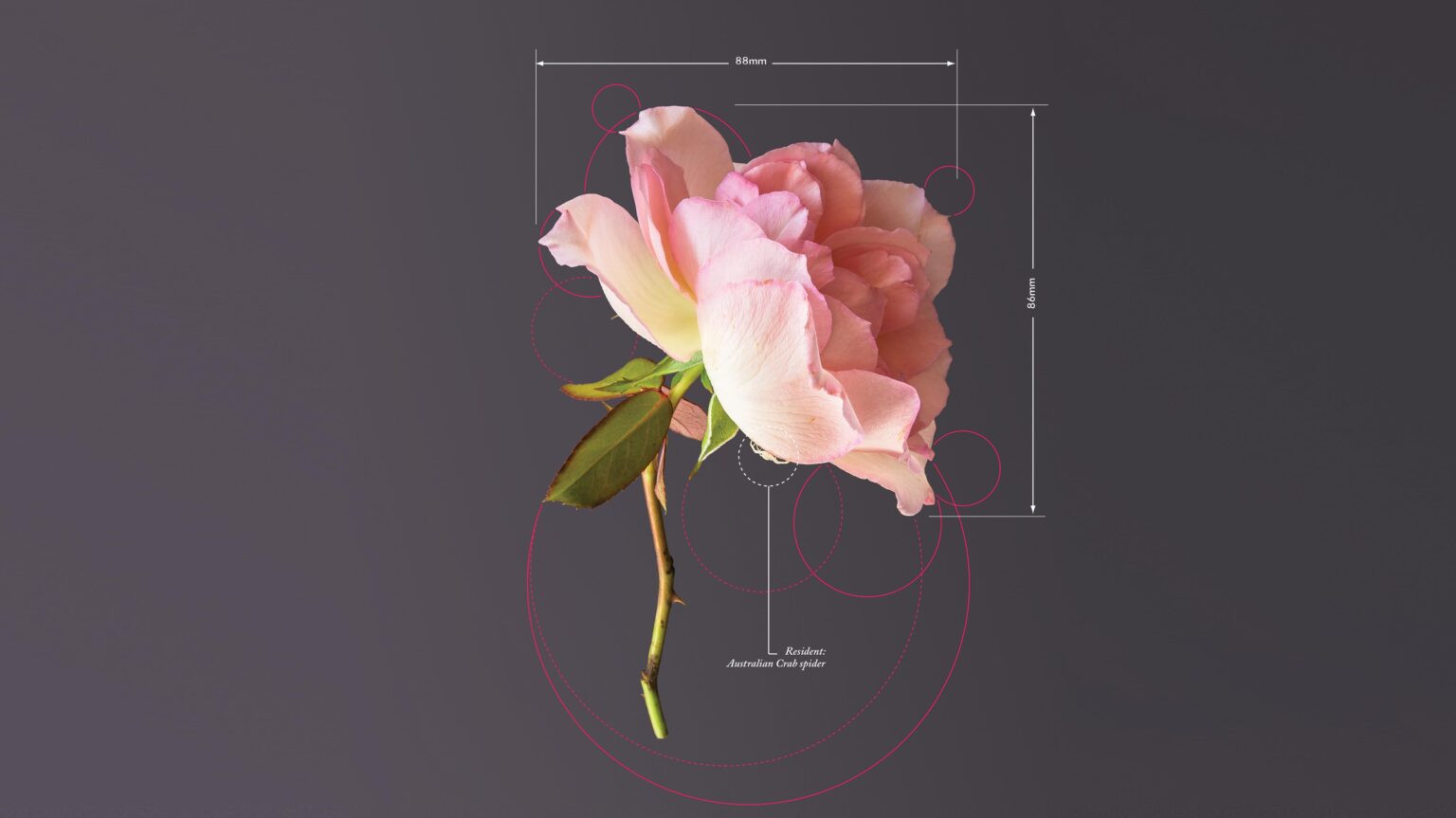

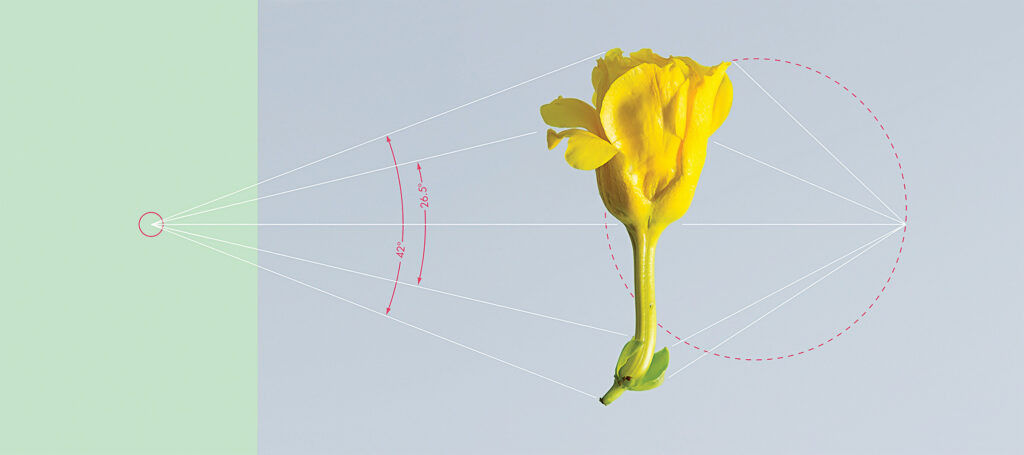

In her series Plant Geometry, visual artist Karina Sharpe explores the inherent paradox of creating an artistic design study of plants as though they were objects with a fixed way of being. 3. Optimize the Impact Intensity of Profits Instead of relying only on conventional cost/benefit analyses and internal rate of return calculations to make budgetary and capital expenditure decisions, companies must begin to use equations that factor in the primary social and environmental effects of their operations. The “impact intensity of profits” is the relationship between a company’s profits and its most important positive or negative effect on ESG issues. For the power company Enel, the primary issue is the environmental impact of its operational footprint, which means the company should make investment decisions that optimize profit per tons of CO2 emitted. For Nestlé, the primary concerns are the nutritional value of its products and the ESG effects of sourcing from smallholders. The company might optimize profit generated per micrograms of nutritional value in its products and the cost of raw materials relative to farmer income and environmental impact in its sourcing. And for BoKlok, a joint venture between Skanska and IKEA, the primary societal benefit comes from expanding access to affordable and attractive housing in urban areas. Up to 40% of its developments are sold to social housing associations. This is the result of a decision-making framework that links profits to specific ceilings on the prices that the associations and other buyers have to pay. Product design, product access, and operational footprint are three domains where companies must change their internal decision-making processes from focusing purely on financial returns to making a more sophisticated analysis that includes social and environmental consequences. The mathematical relationship between changes in environmental or social factors and the resulting changes in profit must become the guiding framework for decision-making at all levels within the company. The results are likely to lead to significantly different choices that not only improve ESG performance but also help reposition the company in ways that improve financial performance. Most firms stop short when they confront trade-offs that require sacrificing profit for improved ESG performance. But those trade-offs often can be avoided. Product design. Nestlé has long been concerned about the nutritional value of its food products, and until 2007, it made the same kinds of modest incremental changes in reducing salt, fat, and sugar content that other major food and beverage companies were making. But beginning in 2007, Nestlé began connecting the material issue of nutrition to its strategy and new-product design. This led the company to invest more than $1 billion annually in research to develop “nutraceuticals,” nutritional supplements with measurable health benefits such as a reduction in postsurgical infections or a decrease in the number of seizures suffered by epileptics. These products, sold not through grocery stores but in pharmacies or administered in hospitals and reimbursed by insurers, have propelled the growth of Nestlé’s nutrition and health science division. It is now the company’s fastest-growing and most profitable division, with more than $14 billion in sales. For Enel, whose main product is electricity, the shift toward a low-carbon world has created new product opportunities. Enel now offers power-management services to its customers: It helps homeowners reduce electricity usage, works with businesses to optimize the operations of fleets of electric vehicles, and guides cities in building infrastructure in ways that continuously minimize power consumption and provide charging options for electric vehicles. Companies that don’t link the social and environmental consequences of their businesses directly to their business models and strategic choices will never fully deliver on their ESG commitments. Tyson Foods will continue to expand sales of beef as the main driver of profits to meet its financial targets even though beef generates the largest amount of greenhouse gas emissions per ton of protein of all the company’s products. If Tyson were serious about optimizing profits and substantially reducing GHG emissions, it would need to make a dramatic shift in strategy and invest much more heavily in plant-based and cellular meat alternatives—a strategy that would dramatically reduce its emissions and potentially increase its profit per ton of protein produced as the plant-based meat segment scales and matures. Product access. The objective of BoKlok is to profitably develop energy-efficient housing that teachers, nurses, and other lower-wage workers can afford to buy or rent. BoKlok uses a detailed analysis of people’s salaries, cost of living, and typical monthly expenses as the benchmark for ceilings on its sale prices. Manufacturing the homes in a factory reduces both the cost of the housing and the carbon emissions produced during construction. (BoKlok has made a commitment to reach net-zero carbon emissions—from manufacturing, sourcing, and even the energy consumption of the homes it builds—by 2030.) Factoring access and affordability into its investment decisions has heavily influenced its choices—such as collaborating with municipalities in Sweden, Finland, Norway, and the United Kingdom to buy land. The reward is a rapidly expanding new market opportunity: Since creating its industrialized affordable-housing model in 2010, BoKlok has built 14,000 homes, while routinely outperforming Skanska’s conventional construction business on a return-on-capital-employed basis. Operational footprint. Greenhouse gas emissions from electricity generation is Enel’s most material issue, along with its customers’ energy use. So Enel has invested €48 billion over three years (2021 through 2023) in renewable power generation, upgrades to improve the efficiency of its distribution network, and new energy-saving technologies for end users. These investments will help Enel reduce its reliance on coal-fired power plants from 10% in 2021 to only 1% by 2023. They will also dramatically increase profit per ton of CO2 emitted and decrease emissions from 214 grams of CO2 to 148 grams CO2 per kWh—while delivering an EBITDA compound annual growth rate of 5% to 6% to shareholders.

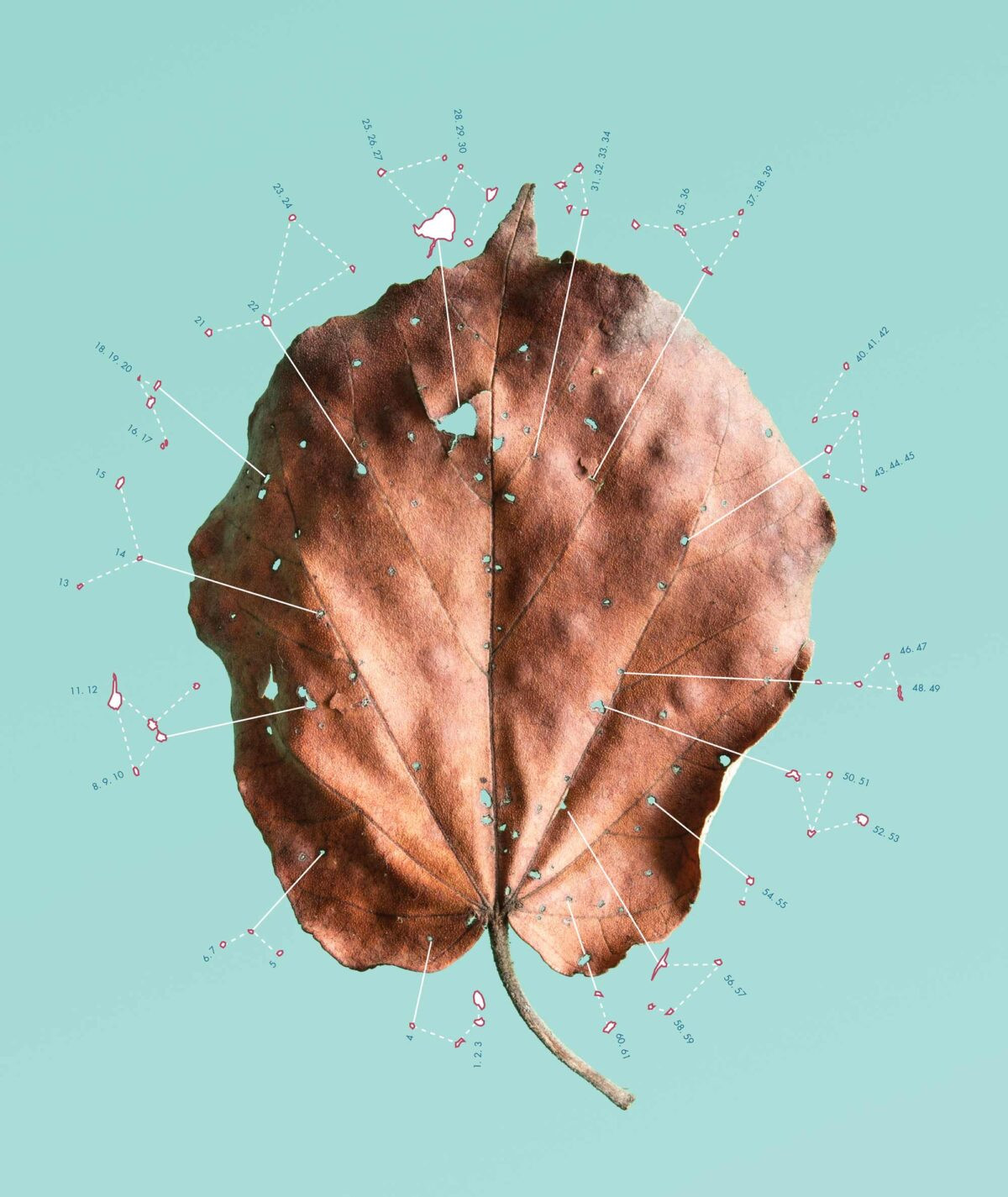

Karina Sharpe A primary issue for Mars Wrigley, as noted above, is the footprint of its commodities sourcing. So the company systematically sets baseline performance measures for climate, water, land, gender-specific income, and human rights across each of its commodities. Each commodity has a different footprint: For cocoa the most critical ESG factors are farmer poverty and deforestation; for dairy products, land and water use are important. Issues vary even within a given commodity: Sugar is a key ingredient in Mars Wrigley’s products, but if it is sourced from beets, the biggest consideration is water use, whereas sourcing from sugarcane raises issues of poverty and human rights. If Mars Wrigley had ignored suppliers’ social and environmental factors, the drive to maximize profit would inevitably have led it to purchase from smallholders with the worst social and environmental impacts, given that labor and environmental practices tend to improve with more sophisticated and costly farming. Buying higher-priced commodities from large-scale commercial farmers might improve the company’s ESG performance, but doing so would also increase its costs and do nothing to reduce the poverty of smallholders and the environmental degradation that their farming practices cause. Integrating sustainability factors into its procurement process has enabled Mars Wrigley to maintain a cost advantage and, by making carefully calibrated investments in helping small farmers, communities, and supply chain partners change their practices, to reduce poverty and harm to the environment. 4. Collaborate to Avoid Trade-offs Between Profit and Societal Benefit Win-win solutions that improve both societal benefits and profits are easy to adopt, but most companies stop short when they confront trade-offs that require sacrificing profit for improved social or environmental performance. Such trade-offs, however, often can be avoided by collaborating with other stakeholders. In fact, many levers that affect a company’s impact intensity of profit are controlled by only a few external stakeholders. Sugarcane cutters in Latin America have, for decades, been paid in cash on the basis of the weight of the sugarcane they cut. The pace at which cutters work determines how much distance they cover in a day, but the weight of the cane they cut depends on factors outside their control, such as the type of sugarcane planted, the irrigation and fertilization practices, and the weather. The team leaders, who traditionally hand out the cutters’ pay, have complete discretion in how much to pay each worker, and there are no controls to ensure that each worker receives his or her due. The result is that many cutters take home far less than a living wage. An ongoing pilot project involving sugarcane mills, purchasers, and local NGOs has found a way to address these issues: It combines a minimum daily wage with additional compensation based on the amount cut. Digital payments are transferred directly to the cutters’ mobile phones to ensure that they promptly receive what they have earned. Together these measures can raise cutters’ wages by 25% while increasing the cost of sugarcane to the mills by less than 5%, most of which is expected to be offset over time through productivity gains. Enel found success with a different type of collaboration. The company needed world-class engineering talent in order to make its shift from fossil fuel to renewable energy, but the most talented environmental engineers did not want to work for an electric utility that still relied heavily on fossil fuel. So the company turned to crowdsourcing. It has posted more than 170 of its most difficult technical problems on its Open Innovability digital platform, which reaches 500,000 “active solvers” from more than 100 countries. So far, they have proposed some 7,000 solutions to those challenges. Enel’s engineers evaluate them and either award cash prizes to winners or establish joint ventures with them. For example, the shift to renewable power depends, in part, on batteries large enough to smooth out the fluctuations in solar- and wind-generated power for an entire city. This is a big challenge because the storage capacity of today’s batteries is severely limited and extremely expensive. As electric vehicles become more common, electric car batteries could be used to store power and provide it when needed. Using just 5% of the stored energy in car batteries could balance the power grid for an entire city. Enel had the idea but lacked the software needed to allow the batteries to contribute electricity to the grid. A six-person start-up based in Delaware learned of the opportunity through the Open Innovability platform and provided the software solution. Collaboration with other stakeholders, whether companies, governments, or NGOs, requires a new degree of cross-sector trust and collaboration. The game of blaming one another for social or environmental problems will have to give way to a partnership in which everyone endorses a shared agenda. In the process, positive outcomes become compatible with profits, and baseline measures, strategies, and investments are developed jointly. 5. Redesign Organizational Roles Despite the increased attention to ESG performance, most companies have done little to change their organizational roles and structures to integrate sustainability into operations. CSR departments are typically very small and uninvolved in strategic and operational decisions. They focus primarily on stakeholder and government relations, philanthropy, and ESG reporting. But if ESG criteria are to be integrated into key decisions, then people with sustainability expertise need to be at the table when strategic and operational decisions are made. Enel has made that change. Its innovation and sustainability functions are combined under a “chief innovability officer,” who oversees, on a matrix basis, a team of people who hail from every department to ensure that all decisions include a sustainability analysis. Mars Wrigley created the combined role of “chief procurement and sustainability officer.” BoKlok and Skanska similarly created an executive vice president position to oversee sustainability and innovation.

Karina Sharpe Incentives must also be aligned. Compensation schemes must reward performance for reaching not just financial but also social and environmental goals. Some ESG-related compensation bonuses are “artfully” designed so that they can be awarded even if emissions increase or environmental damage worsens. Obviously, that renders such incentives ineffective. Companies that take ESG goals seriously make sure that a significant part of executives’ bonuses are dependent on achieving them. At Mars, the top 300 corporate leaders receive long-term incentive compensation (above salary and annual bonuses) on the basis of their success in achieving equally weighted financial and emissions-reduction goals over a three-year period. And Mastercard recently announced incentive compensation for all employees that includes performance metrics around three material issues: carbon emissions, financial inclusion, and gender equity. 6. Bring Investors Along Companies must explain to investors their strategies for improving the impact intensity of their profits, communicate their commitments to achieving explicit goals, and report publicly on their progress. Spelling out how the company is incorporating positive social impact into its business model will carry far more weight with investors that care about climate targets and sustainable development goals than flawed and inconsistent ESG rankings. Nestlé, for example, which has been steadily reducing sugar, salt, and fat across its product portfolio for more than a decade, began only in 2018 to disclose to investors that these healthier foods had faster growth rates and higher profit margins than traditional offerings. Enel has long described its shift to renewables in its sustainability reports and taken pride in its efforts to advance the UN’s Sustainable Development Goals, but only in November 2019 did it first highlight the financial value driven by the renewables business model in its Enel Capital Markets Day investor presentation. In the following three months, when most stocks plunged because of the Covid-19 pandemic, Enel’s share price increased almost 24%, a change that management attributes to this shift in communication strategy. Unless companies clearly explain the financial benefit of their ESG improvements to their investors, they will not see the value of those efforts reflected in their share prices. We cannot continue the path we are on today, where companies’ social and environmental actions are after-the-fact interventions disconnected from strategy and decision-making. Focusing on shared value and the economics of impact will lead companies to make fundamental changes to their business models, capital investments, and operations, generating meaningful opportunities for differentiation and competitive advantage. In doing so, they will create an economy that truly works to close social inequities and restore natural ecosystems. A version of this article appeared in the September–October 2022 issue of Harvard Business Review. Read more on Sustainable business practices or related topics Strategy, Operations strategy, Business models, Corporate social responsibility, Product development, Business and society and Society and business relations Mark R. Kramer is a senior lecturer at Harvard Business School. He is also a cofounder of the social impact consulting firm FSG and a partner at the impact investing hedge fund at Congruence Capital. Marc W. Pfitzer is a managing director at FSG, a global social-impact consulting firm.

| The text being discussed is available at | https://hbr.org/2022/09/the-essential-link-between-esg-targets-financial-performance and |