Date: 2025-01-15 Page is: DBtxt003.php txt00008906

UNILEVER

SUSTAINABILITY

Waste reduction is central to Unilever’s sustainability strategy

SUSTAINABILITY

Waste reduction is central to Unilever’s sustainability strategy

Unilever's Sustainable Living Plan.

http://www.packworld.com/sustainability/strategy/waste-reduction-central-unilever%E2%80%99s-sustainability-strategy

Peter Burgess COMMENTARY

Unilever's commitment to sustainability is impressive. Paul Polman, Unilever's Chairman put sustainability right in the middle of Unilever operations, rather than having it hanging on to the outside of the mainstream activities of the business.

Paul Polman is no longer in the company and it is not as clear now (June 2022) where sustainability fits into Unilever's current operational behavior. Some outsiders have tried to take over the company in the last few years (I think in 2019) with the belief that more profits could be made by trashing the company's sustainability agenda. This was defeated, but Paul Polman is no longer the Chairman.

Peter Burgess

Unilever senior packaging manager, R&D, Michael Hughes, shares how the company is evaluating and designing its packaging to meet the goals of The Sustainable Living Plan.

By Anne Marie Mohan, Editor, Greener Package

ARTICLE | FEBRUARY 1, 2013

In November 2010, Unilever launched a new strategic business direction in the form of The Sustainable Living Plan, a company-wide initiative to double the size of the business by 2020 while reducing emissions by half in that same time frame. Unilever is one of the world’s leading suppliers of food, home, and personal care products, with global sales of more than $67 billion in 2012. More than 2 billion people use Unilever’s products on a daily basis. The Sustainable Living Plan encompasses the entire value chain, with Unilever taking responsibility not just for its own direct operations, but also for its suppliers, distributors, and consumers. Underpinning the plan are more than 50 targets.

In considering the environmental impact of its products, Unilever undertook a comprehensive Life Cycle Analysis of 1,600 of its products. Through the analysis, it determined that the largest source of its waste results from packaging. This prompted the company to put in place several targets aimed at reducing packaging waste across the value chain. These include reducing the weight of its packaging by one-third by 2020; working with partners to increase recycling and recovery rates in its top 14 countries up to 5% by 2015, and up to 15% by 2020; and increasing the recycled material content of its packaging to maximum possible levels by 2020; among others.

In an exclusive interview with Packaging World, Michael Hughes, senior packaging manager, R&D, at Unilever, details how the company is working toward these goals to reduce the impact of its packaging on the environment.

Packaging World:

According to a press release on The Sustainable Living Plan, the plan is “one of the largest and most innovative sustainability platforms to-date.” Does this mean it is the largest and most innovative of platforms undertaken by Unilever, or by the CPG industry overall? What makes this such a large and innovative plan?

Michael Hughes:

It certainly is the biggest plan within Unilever and I even think outside of Unilever, as well. It’s very comprehensive. The Sustainable Living Plan has three significant outcomes: It has to do with helping a billion people, decoupling growth from environmental impact, and enhancing livelihoods.

Packaging is part of the second goal—decoupling growth from environmental impact and achieving reductions across the life cycle of our products, and even more specifically, across the life cycle of our packaging. Most of that is waste. So within waste, and I assume in the other areas as well, we have specific targets. These targets are measurable, and we report on our achievements toward these targets. I think it’s kind of unique to have measurable targets.

The Sustainable Living Plan is our business plan; it is not part of our business plan. This is our overall business strategy. So I think that separates us from a lot of other companies.

If Unilever categorizes packaging as waste, when you design a new package, are you mainly looking at ways to keep that material out of the landfill? Is your end goal to get as close to zero waste as possible with packaging?

The answer is yes. Our goal is to follow the waste hierarchy set forth by the Environmental Protection Agency. [The EPA’s Solid Waste Management Hierarchy lists, from most to least preferred actions: source reduction and reuse; recycling/composting; energy recovery; and treatment and disposal.] It is to reduce packaging, reuse packaging, and recycle packaging, and we have specific goals within each of those three targets. We have published design guidelines within Unilever for our packaging engineers and marketers to follow. The guidelines are consistent with the Sustainable Packaging Coalition design standards and the Association of Postconsumer Plastic Recyclers standards. Then for all new products and new packaging, a scorecard needs to be filled out that is used at each stage of the approval process. We go through stages, and each stage has to be approved by the leadership of that category. They are looking at that scorecard and making sure the design is consistent with Unilever’s goals.

The guidelines and scorecard are used on a global basis, and then we have some products that are local, for instance, Ragú spaghetti and pasta sauce in North America. So local employees, as well as global employees are following these design guidelines and are using the scorecard.

You noted that the guidelines used by Unilever are based on established standards, but they have been customized for your organization, correct?

That’s right. When you design packaging, there are competing interests. Certainly sustainability is one of them, but there are marketing interests. Our marketers are looking for real estate for communication. There is the manufacturing efficiency; the packaging has to run with great efficiency within our plants. It has to contain the product, preserve the product, go through transportation—all these factors at times can be competing interests. So our internal design guidelines balance those interests and also help us meet our sustainability goals.

If you are approaching packaging design in terms of reducing waste at the end of life, does this mean the design process does not look as much at upstream considerations, such as which material requires more energy to manufacture, or which requires more water?

We have looked at the types of materials that we would prefer to use. If we can use, for example, high-density polyethylene for a bottle instead of polypropylene, our guidelines tell us to do that because the regional recovery index is higher for HDPE. But we wouldn’t use something that has a negative impact upstream. An example might be bioresins. Right now, we are not using bioresins. We are not saying we are not going to use them; we are going to keep an eye on that industry. But until we see conclusive data that shows that there is not a negative energy impact, we are taking a wait-and-see approach. In other words, if you are making bioresins from sugarcane grown in Brazil, and you are shipping those materials all the way up here, what does that total life cycle look like? We haven’t seen a good, positive result on that yet.

Do having these guidelines and preferred material recommendations ever stifle innovation around sustainable packaging design?

We are really depending on outside innovation to help us meet our goals. Unilever’s goals are so aggressive that we don’t know how we are actually going to reach all of them right now. So we are depending on partnerships and suppliers to bring in new materials and methods that we can use. So yes, there is that flexibility.

I understand Unilever performed Life Cycle Assessments on 1,600 representative products. Can you share what you learned from this undertaking?

We looked at four areas when we calculated the environmental footprint of each product. We looked at wastewater, greenhouse gas, waste, and sustainable sourcing. So, within those categories, packaging has the greatest impact on waste, although it does impact all the categories. In the area of product waste, 59% comes from the primary packaging, 14% from transport packaging, and 27% from product leftovers.

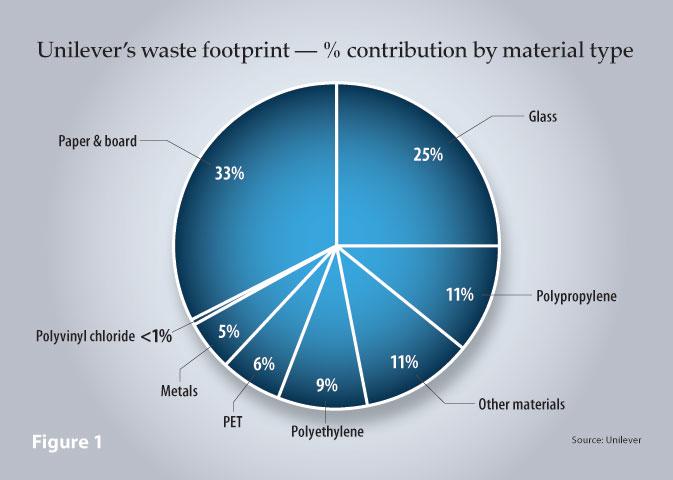

The way we define waste is we add the weight of the primary package plus the weight of the secondary package, plus the weight of product leftovers, and then we subtract the regional recovery index. By recovery, we mean both recycling and waste-to-energy. Waste-to-energy is not too much of a factor in the U.S., but it is big in Europe and other places. That’s how we get our footprint. So, according to our metrics, paper is the largest contributor to our waste footprint [33%], and then glass [25%], and then polypropylene [11%], and so on. (See Figure 1.)

When we break down our waste footprint by product category, our analysis showed that our food packaging—specifically packaging for soups, sauces, and stock cubes, and tea and beverage packaging—and our soap, shower gel, and skin care packages are the biggest contributors [at 21%, 13%, and 13%, respectively]. (See Figure 2.)

Are these charts helping you to better focus on those areas where you need to make package design changes or get more involved in recycling efforts to try to increase the recovery rates?

Absolutely! At the beginning of 2010, we sat down with each of the product categories in each of the regions, and we showed them their individual contribution to the waste footprint, by material type and by product line. With that, we were able to set up specific targets for each category in each region. So we have global targets, and we also have regional targets. That’s part of how the performance of each of the different product groups is judged—by the ability to meet those agreed-upon targets for waste.

Are there any materials currently that Unilever will not use in its products/packaging?

Polyvinyl chloride. We have a global policy not to use PVC because in some areas there is still open burning of waste, and it’s toxic. Here in the U.S. and in other countries that recycle polyester, PVC is a contaminant to the recycling stream. So it’s not allowed here in North America; we have completely eliminated it.

Can you provide a couple of examples of new package designs or redesigns of existing packages that were done in the last year or two with an eye toward reducing waste?

We have examples that fall under two categories. First, we have the target of reducing the weight of our packaging by a third by 2020 through lightweighting, optimizing design, etc. We’ve already achieved a 4% reduction against that target. So that’s pretty good.

There are a number of examples that fall under this category. For our margarine cartons, we achieved a 12.5% decrease in weight by reducing the paperboard caliper from 12.0- to 10.5-pt SBS. For our deodorant packaging, we borrowed technology from the auto industry. For years, they have been using a blowing agent during the plastic molding process that creates bubbles in the plastic components used around the dashboard, so they can use less resin and still have the same part thickness. We have done that with our deodorant sticks and have saved 392 tons of resin a year.

Our margarine tubs were also redesigned to eliminate 2.5 g of plastic per pack. We sell many millions of margarine tubs. For our foodservice tea dispensers, we decreased the envelope sizes anywhere from 18% to 25%, depending on the variety, reduced the carton weight by 14%, and reduced the shipping case weight by 5%. Not too long ago, we changed the Wishbone salad dressing bottle design, and we reduced plastic by 23% by doing that. The examples go on and on. With the Suave For Kids shampoo bottle redesign, we saved resin in both the cap and the bottle; for Axe body spray aerosols, we reduced the package weight and saved 324,000 pounds a year of aluminum.

The other target area is in the use of recycled content in our packaging. We recognize that to stimulate recycling in the U.S., you have to create demand for the resin. So, one of our targets is to use as much recycled material as possible. I think we are using 1,700 tons of post-consumer recycled material now.

Here in the U.S., we have specific examples of this: Our St. Ives lotion in three bottle sizes uses 20% PCR HDPE; three sizes of Axe body wash use 25% PCR HDPE; Dove Men Care body and face wash in two bottles sizes uses 25% HDPE; and there are other examples as well.

There is one other area that I wanted to mention as part of this—it is the target of working with NGOs to increase recycling rates. We said we were going to increase recycling rates 5% by 2015, and 15% by 2020. Here in the U.S., we are partnering with FundingFactory, Earth911, and NextLife on a deodorant stick package-recycling project.

NextLife is a processor of polypropylene, and they have the only PP resin approved by the FDA for direct food contact. We have partnered with them because of their expertise. We are going to collect 4,000 to 6,000 pounds of deodorant stick packages from 50 participating high schools and colleges, and we are going to recycle them at NextLife.

We have already recycled packaging from our deodorant stick manufacturer that doesn’t have any deodorant in it, and it worked out well. NextLife thinks they have a method to get rid of the residual product. We will then publish our results on the PP recycling value chain through trade organizations. We are hoping that with this experiment, if it is successful, we can convince recyclers that they can make money by accepting and recycling deodorant sticks.

Right now these packages are hardly accepted at all. I think Tom’s of Maine has a special mail-in program set up, but other than that, they are basically not being recycled. But just like other packaging material, it really shouldn’t be waste. It should be a resource to be used, and the recycling value chain can make money from this. This is the type of work that we are doing to try to stimulate recycling.

So rather than helping to expand recycling systems, Unilever is working to prove the value of recycled materials and to use packaging materials that are suitable for recycling?

Yes. Our goal is to work with existing systems. So if we can develop packaging that is already recyclable, that’s definitely a higher priority. But if there are certain technical reasons that we can’t—like in the case of deodorant sticks, where it’s a multi-component assembly that is made with two different types of resin—we feel we need to help the existing system see that they can recycle the packaging.

What are some of the challenges Unilever faces in reaching its goal of increasing the recycled material content of its packaging to “maximum possible levels” by 2020?

There are really two things that are slowing us down. One is cost. In most cases, it is more expensive to use recycled material than virgin, but we’ve made the commitment, and as we just talked about, we are using it where we can. The other barrier is performance. For HDPE and I think the same is true with PET, that 20% to 25% level seems to work well at our processors and converters. Once we climb above that, we start to see either a slowdown in cycle times or sometimes a decrease in quality, but 20% to 25% seems to be optimal right now.

Is Unilever looking at packaging solutions that address the food waste issue?

Yes, that’s one of our goals. We have projects ongoing right now that target the hotspots identified by our product LCAs, but I can’t talk about them yet.

What is Unilever’s position on waste-to-energy as a means of recovering energy from discarded packaging?

We see waste-to-energy as a viable option for things that can’t be recycled.

What are your thoughts on composting?

We absolutely prefer it versus putting packaging material in a landfill.