Date: 2026-03-02 Page is: DBtxt003.php txt00022777

ECONOMIC ANALYSIS

A GOOD CRITICISM

CNBC The tiresome doomsday data-point watching

A GOOD CRITICISM

CNBC The tiresome doomsday data-point watching

Original article: https://link.cnbc.com/public/28452503

Peter Burgess COMMENTARY

I don't know how many people actually understand the economic data that is compiled month by month by government departments of statistics around the world, and perhaps even more important, how many of the people who write about or talk about economic news have even a rudimentary understanding of what the data really show.

This material is a reminder of the complexity of the economic system, not to mention the much bigger socio-enviro-economic system that is actually the driver of everything. In particular, analysts get things wrong when they try to simplify complex behaviors into something that is easy to understand.

In my normal analysis approach, I am always asking what is behind the single number that is being tracked. Most of the time, the average is wrong, because it comprises some results that are better than average and some that are worse than average. It matters what 'shape' of data gives the average.

I am also as careful as I can be to differentiate between 'causation' and 'correlation'.

I may not be as careful as I should be in differentiating between data based on reality and date that is flowing from some active source of misinformation or worse. People, including myself, are anxious to get validation of our 'point of view' and deeply held beliefs ... not matter what factual data should be telling us.

I think there is another factor in play ... something that I was faced with early in my 'management' career. People very quickly learn how to 'game' the numbers, and the ways this is done can be very sophisticated. In the modern economy there are many sides but for simplicity's sake let us talk just about the 'investors' or 'owners' and 'workers' or 'everyone else'. The investor group wants the economy to deliver more profit and everyone else wants the economy to deliver a better quality of life and on the face of it ... or more accurately, the way we measure things and function ... this is a reality. But it need not be. We ... or really those with power and influence ... have chosen to make the choice

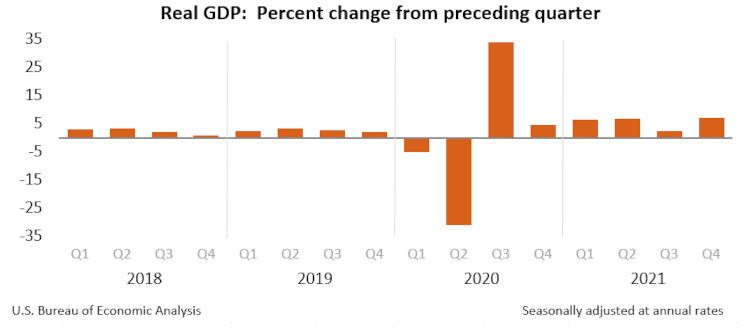

The US economic growth data for the past several quarters is interesting ... but what does it show? One thing is obviously that the 2nd and 3rd quarters of 2020 were not normal. First there was a massive economic contraction and then there was a massive economic expansion both explained by the impact of Covid on economic activity ... an economic disruption that was one of the biggest in all of history.

But what else does the graph show? Perhaps it shows that the growth in 2022 (in the Biden era) is substantially stronger than the economic growth in 2020 (in the Trump era).

I don't consider this to be conclusive ... but it does suggest that the Biden economic team has been doing something right. The next step has to be to confirm what is going on in more detail by sector, by place and by demographic. That will be addressed as soon as I can get round to it.

Peter Burgess

The tiresome doomsday data-point watching

Written by Kelly Evans

THU, JUL 21, 2022 ... 11:05 AM

- DJIA 31707.17 -0.53% -167.67

- S&P 500 3957.43 -0.06% -2.47

- NASDAQ 11913.01 +0.13% +15.36

It all feels a little too simplistic right now. Every time a macro datapoint comes in weak, you get throngs of sinister charts and tweets ominously suggesting that 'the turn is happening...the data points are starting to roll over...this is the biggest two-month drop in xxx since xxxx...this is classic Fed tightening into a downturn,' etc., etc., etc.

Let me ask you something. If we needed to slow nominal GDP from, say, a 9% pace down to a healthier, more-sustainable, less inflationary 4% pace, what do you think would happening to the macro datapoints? Would jobless claims be rising? Probably! Would manufacturing surveys be softening? I would guess so. What about home prices? I doubt they'd be surging. But would it all mean a disastrous downturn was coming? Not necessarily.

Of course the Fed can't be precise enough with monetary policy to accurately slow nominal growth from the actual 10.1% pace we saw last year (after only a 2.2% drop in 2020) to the specific level of 4% that is necessary in the long run. Why 4%? That basically allows for 2% or so real growth, and 2% or so inflation. The mix itself can't be determined by the Fed either, obviously. Real growth depends on productivity and population growth, which are tough to engineer in real time.

So the Fed might slow things down too much--which is the predominant scare right now every time a data-point softens--or too little, in which case inflation will stay maddeningly persistent. The only way to 'know' is to see what the market's best guess at any particular moment is, based on things like inflation expectations, long-term and short-term interest rates, stock prices and multiples, and so forth.

And right now, the market is sending much more encouraging signals about the economy. Yes, I said 'encouraging.' As we've discussed, inflation expectations are way down, to just under 2.7% per year for the next five years, versus 3.6% at the peak in late March. Stock prices and valuations have massively reset, as they should if nominal growth is slowing from 10% to perhaps half of that or less. Home prices--well, at least they've stopped surging, and housing activity has slowed.

But the yield curves are inverting! Yes, the two-year yield is higher than the 10-year right now, so that curve has inverted. A lot of traders prefer the three-month versus 10-year yield, however, and the three-month Treasury bill yield is still a half point lower, so that curve has not yet inverted. It has flattened dramatically this year, but again, that's in keeping with the Fed's need to slam the brakes on nominal growth, which it let run far too hot as it expanded its balance sheet by nearly five trillion dollars after the pandemic hit while watching D.C. inject a similar amount of stimulus into the economy.

And it's still about a year after the three-month/10-year inversion before a recession typically hits the economy, notes Michael Darda of MKM Partners. So we're talking about a mid-2023, if not later, type of event. Which is also what Aneta Markowska of Jefferies has been saying. Still, people seem confused as to why the Fed would intentionally trigger a recession. The larger point is it has to slow nominal GDP. It's kind of hard to do that with the pinpoint accuracy that would guarantee the business cycle doesn't roll over.

For now, we need the macro datapoints to be slowing. They certainly can't keep soaring, pushing inflation over 9% and the economy close to its breaking point. So I just can't get that worked up about jobless claims rising from around 150,000 a week last fall to 250,000 a week now--which is still low by historical standards. Or the litany of tech companies 'slowing their pace of hiring,' which is basically what the Fed is trying to achieve anyhow.

Could there come a time when the datapoints become truly terrifying, a la 2007-08? Of course. But there's no guarantee we are headed there. And just as scary in a subtler sense would be datapoints that don't slow enough. I don't want years more of 6% or even 5% or 4% inflation, chronic labor shortages, brittle supply chains, and a less-productive economy.

People act like the economy only needs one little push, like the Fed's last rate hike, to fall off a cliff and slide back into deflation. I'm not so sure. It may turn out that beating inflation requires a far larger and more sustained effort than that. And we are barely a few months into this journey.

See you at 1 p.m!

Kelly

Written by Kelly Evans ... Twitter: @KellyCNBC ... Instagram: @realkellyevans