Date: 2026-01-28 Page is: DBtxt003.php txt00027720

IGNORANCE

MOR COMMON THAN COMMON SENSE

NYT Opinion: Guest Essay: The Surprising Allure of Ignorance

MOR COMMON THAN COMMON SENSE

NYT Opinion: Guest Essay: The Surprising Allure of Ignorance

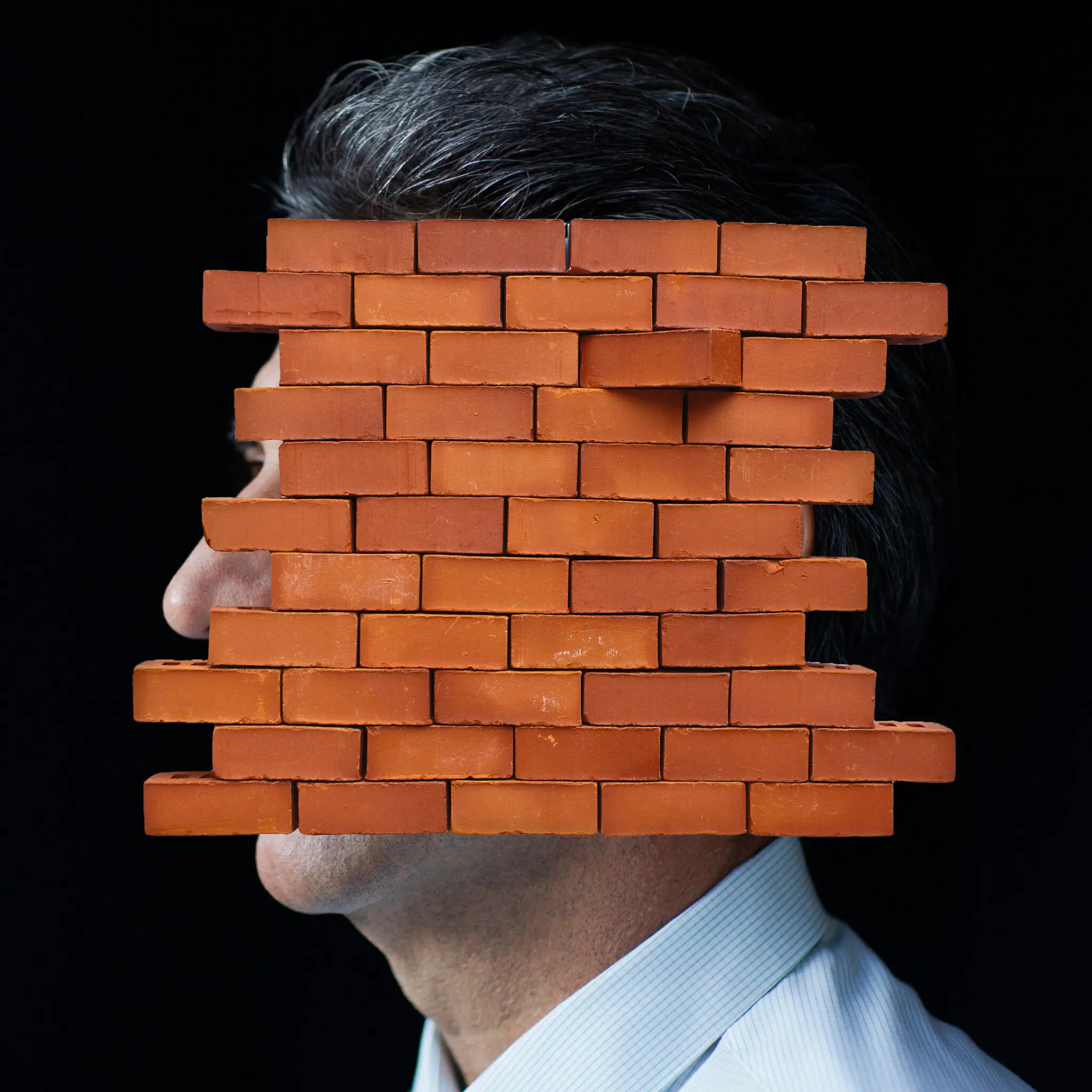

A man stands behind a wall of bricks. His face is mostly hidden, but his nose and chin peek out.

Credit...Illustration by Frank Augugliaro/The New York Times. Photographs by Getty Images

Original article: https://www.nytimes.com/2024/12/02/opinion/ignorance-knowledge-critical-thinking.html

Peter Burgess COMMENTARY

I have been very fortunate. Both my parents were well educated in the UK and had a strong committment to the idea that I should getr the best possible education. After that, it was going to be up to me what I did with my life!

My education at Blundells ... a boys' boarding school in Tiverton in the West Country of England established in 1604 was rigorous and a good balance between academics and sports (mainly rugby and cricket). I believe my class ... the class that graduated in 1958 ... had best results ever in respect of getting acceptance to universities and especially Oxford or Cambridge.

I got a scholarship to Sidney Sussex, Cambridge and entered the University in September 1958 to study engineering ... the Mechanical Sciences Tripos. The university intake of 1958 was a little unusual in that there had been an important change in the rules for 'National Service'. Boys in my age group were no longer required to serve in the UK military for two years after leaving school. Accordingly the university intake for that year was made up of both those that had served and completed national services and those of us who had come directly from school. There was a similar mix of university entrants the following year, and by the third year almost all the new students were coming straight from school.

This was a very significant change with substantial impact on student outcomes. My own academic training was likely a lot faster because I did not serve in the British military, but my world knowledge was way more limited. I think this was true for all my cohort going through university at that time. At the end of this change, the university was probably more 'academic', but most likely, significantly less relevant. My impression is that this has 'rebalanced' over subsequent years and decades with intellectual progress improved substantially over time especially as it relates to post-graduate studies.

A much bigger proportion of students now go to university now than six decades back when I was a student. Now it is maybe 30% compared to less than 5% when I was a university student. My impression is that this is both good and bad. In my view. more than 5% of young people can benefit from a university education and get meaningful value from the experience but it is way less than the 30% or more that are currently going through the experience. Maybe the number should be 10% or 15%, but probably nowhere near the 30% that I understand is the current number!

The USA has been offering low level undergraduate education for a very long time, In 1960 when I was a student in the UK, I visited Canada and the United States. In Canada, university students at the same stage of their education appeared to be about an academic year behind me which came as a big surprise to me. However, when some Canadians and I travelled through the USA we learned that the Americans were a year behind the Canadians.

The elite American universities are world class ... but most American university education costs a lot of money and delivers a poor outcome. My experience in 1960 has not been rectified in the subsequwnt six decades or more but has probably degraded even more.

Immigrants to the United States ... both legal and otherwise ... have become a key part of the American workforce. Some of this is why America has become so stressed with a big part of the population unable to earn enough to meet even basic expendures. Sadly ... Trump is likely to make the situation much worse and it does not seem likely that he will care!

Peter Burgess

The Surprising Allure of Ignorance

Dec. 2, 2024, 5:02 a.m. ET

Written by Mark Lilla ... Mr. Lilla is a professor of humanities at Columbia University and the author of the forthcoming book “Ignorance and Bliss: On Wanting Not to Know,” from which this essay is adapted.

Aristotle taught that all human beings want to know. Our own experience teaches us that all human beings also want not to know, sometimes fiercely so. This has always been true, but there are certain historical periods when the denial of evident truths seems to be gaining the upper hand, as if some psychological virus were spreading by unknown means, the antidote suddenly powerless. This is one of those periods.

Increasing numbers of people today reject reasoning as a fool’s game that only cloaks the machinations of power. Others think instead that they have a special access to truth that exempts them from questioning, like a draft deferment. Mesmerized crowds follow preposterous prophets, irrational rumors trigger fanatical acts and magical thinking crowds out common sense and expertise. And to top it off we have elite prophets of ignorance, those learned despisers of learning who idealize “the people” and encourage them to resist doubt and build ramparts around their fixed beliefs.

It is always possible to find proximate historical causes of these upsurges in the irrational — war, economic collapse, social change. But doing so can distract us from recognizing that the ultimate source lies deeper, in ourselves and in the world itself.

The world is a recalcitrant place, and there are things about it we would prefer not to recognize. Some are uncomfortable truths about ourselves; those are the hardest to accept. Others are truths about the reality around us that, once revealed, steal from us beliefs and feelings that have somehow made our lives better, easier to live — or at least to seem that way. The experience of disenchantment is as painful as it is common, and it is not surprising that a verse from an otherwise forgotten English poem became a common proverb: Ignorance is bliss.

We can all find reasons we and others avoid knowing particular things, and many of those reasons are perfectly rational. A trapeze artist about to climb the pole would be unwise to consult the actuarial table for those in her line of work. Even the question “Do you love me?” should pass through several mental checkpoints before being uttered.

Sign up for the Opinion Today newsletter Get expert analysis of the news and a guide to the big ideas shaping the world every weekday morning. Get it sent to your inbox. But each of us also has a basic disposition toward knowing, a way of carrying ourselves in the world as experiences come our way. Some people just are naturally curious about how things got to be the way they are. They like puzzles, they like to search things out, they enjoy learning why. Others are indifferent to learning and see no particular advantage to asking questions that seem unnecessary for just carrying on.

And then there are people who, for whatever reason, have developed a particular antipathy toward the search for knowledge, whose inner doors are fastened tight against anything that might cast doubt on what they believe they already know. These attitudes are not limited to the uneducated: We have all also fallen into moods where they emerge in ourselves, however uncharacteristically.

Why does this happen? Because seeking and having knowledge is not just a cognitive pursuit; it is also an emotional experience. The desire to know is exactly that, a desire. And whenever our desires are satisfied or thwarted, our feelings are engaged.

Given how rapidly everything changes in life today, doesn’t it often feel better to rest on our intellectual and moral laurels? Why seek truth if truth will require us to do the hard work of rethinking what we already know? Just as we can develop a love of truth that stirs us within, so, too, we can develop a hatred of truth that fills us with a passionate sense of purpose. There can be a clash of emotions, with the desire to defend our ignorance standing as a powerful adversary to the desire to escape it.

One source of this clash is that we consider our opinions to be an extension of our selves, a prosthetic device. When they are attacked or dismissed, we feel that something intimate has been touched. And when our opinions are shown to be wrong, we feel ashamed. Socrates maintained that there is no shame in being wrong, just in doing wrong. He was right. But it’s not the way we initially feel, especially when someone else exposes our errors.

No argument is disembodied. Behind every assertion there is an asserter, and it is he, not his assertion, who wounds our pride. Strange as it may seem, mathematicians and scientists debating matters at the furthest remove from their daily lives can be as dogmatic and touchy as any political partisan. A new elementary particle has been discovered: Is that one giant leap for mankind or one point for our side?

At some point we all decline the opportunity to discover what really is the case. We willingly give up a shot at learning the truth about the world out of fear that it will expose truths about ourselves, especially our insufficient courage for self-examination. We prefer the illusion of self-reliance and embrace our ignorance for no other reason than it is ours. It doesn’t matter that reliance on false opinion is the worse sort of dependence. It doesn’t matter that through stubbornness we might pass up a chance at happiness. We prefer to go down with the ship rather than have our names scraped off its hull.

So as we shake our heads at those charmed by charlatans and demagogues, let us not exempt ourselves. We all want to know — and want not to know. We accept truth, we resist truth. Back and forth the mind shuttles, playing badminton with itself. But it doesn’t feel like a game. It feels as if our lives are at stake. And they are.

More on critical thinking

- Opinion | Nathan Ballantyne and David Dunning ... Skeptics Say, ‘Do Your Own Research.’ It’s Not That Simple. Jan. 3, 2022

- Opinion | Gordon Pennycook and David Rand Why Do People Fall for Fake News? Jan. 19, 2019

Follow the New York Times Opinion section on Facebook, Instagram, TikTok, WhatsApp, X and Threads.

Editors’ Picks

- Am I a Hypocrite for Calling Donald Trump a Liar?

- Dinosaur Domination Is Marked in a Timeline of Vomit and Feces Fossils

- As Their Business Flourished, the Marriage Floundered